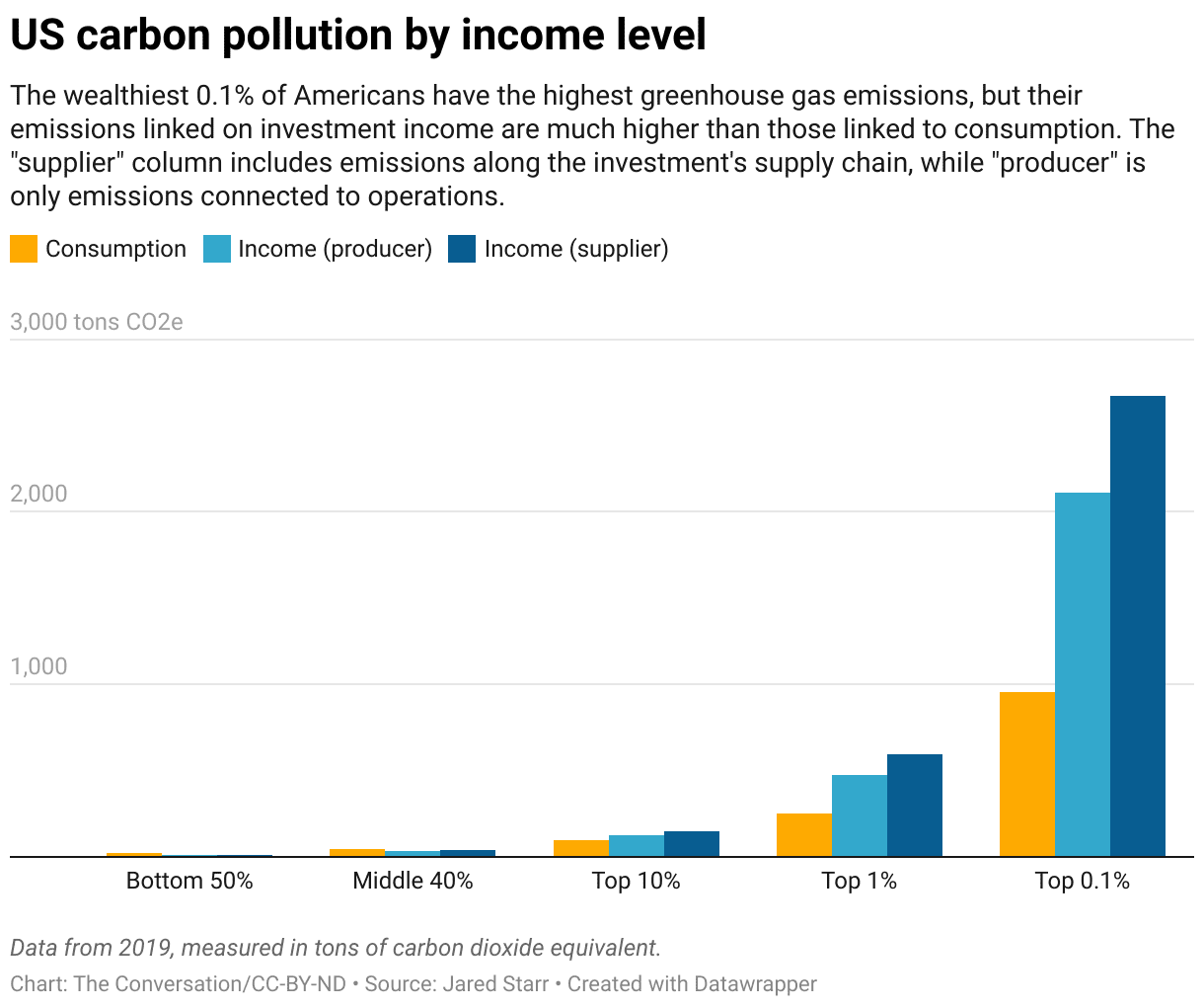

The wealthiest 10 per cent of Americans create 40 per cent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, a new study shows, and the authors are suggesting a new carbon intensity tax on investments might encourage these big emitters to clean up their act.

A team led by Jared Starr, a sustainability scientist at UMass Amherst and the lead author of the study, looked at 30 years’ of data to calculate supplier-based and producer-based greenhouse gas emissions in passively-generated investment income.

Supplier-based emissions are those created by industries that supply fossil fuels to the economy. For example, the operational emissions released by fossil fuel companies are actually quite low, but they make enormous profits by selling oil to others who will burn it.

Producer-based emissions are those directly released by the operation of the business itself—like a coal-fired power plant.

By linking that emissions data with income data from some 5 million Americans, they were able to find who is making their money from dirty investments.

“This research gives us insight into the way that income and investments obscure emissions responsibility,” says Starr.

“For example, 15 days of income for a top 0.1 per cent household generates as much carbon pollution as a lifetime of income for a household in the bottom 10 per cent. An income-based lens helps us focus in on exactly who is profiting the most from climate-changing carbon pollution, and design policies to shift their behaviour.”

The team found the top 1 per cent of earners alone generate 15 – 17 per cent of the nation’s emissions and in general, white, non-Hispanic households had the highest emission-linked income.

Black households had the lowest emission-linked income.

Emissions tended to increase with age, peaking with the 45–54 age group, before declining.

The so-called ‘super emitters’ are the wealthiest 0.1 per cent of Americans, whose investments are overrepresented in finance, real estate and insurance, manufacturing, and mining and quarrying.

Tax investments, not consumption

By thinking of carbon emissions as an outcome of income generation rather than consumption, new policies to speed up decarbonisation – and revenue generation – are possible, says the study, published in PLOS.

This might include an income or shareholder-based carbon tax that reflects the greenhouse gas intensity of the financial assets and put pressure on executives and large shareholders to take action in order to reduce taxes on their compensation and investments.

“Consumption-based approaches to limiting greenhouse gas emissions are regressive. They disproportionately punish the poor while having little impact on the extremely wealthy, who tend to save and invest a large share of their income,” Starr says.

“Consumption-based approaches miss something important: carbon pollution generates income, but when that income is reinvested into stocks, rather than spent on necessities, it isn’t subject to a consumption-based carbon tax.”

The report noted that the US has struggled to get consumer-facing carbon taxes over the legislative line, but an investment-based carbon tax might be more equitable, politically palatable, and equally justifiable – if it wasn’t killed by “significant pushback from the economically advantaged households who dominate policymaking”.

Rich are set to lose anyway

If an investment tax doesn’t push the world’s wealthiest to change their ways, the fact that fossil fuel assets are – many hope – a dying breed may.

In June a study, also out of UMass Amherst, found investment losses caused by climate action on fossil fuel businesses would be overwhelmingly felt by the most affluent and have a minimal impact on the general populace.

The inference is that for countries like Australia, where fossil fuel industries account for large proportions of retirement savings, the impact will be minimal as it is comparatively cheap for governments to compensate for those losses.

However, even though the weight of financial loss falls mainly on the rich, it still makes up a small percentage of their total wealth.

“Investing in a stranded asset is like buying a rotten apple,” says co-first author Lucas Chancel, an economics professor at Sciences Po in Paris.

“In this case, the apple is rotten because of climate change. Who owns these rotten apples? We find that the richest 10 per cent of the population owns the vast majority of these assets.”

UMass Amherst economic professor and co-first author Gregor Semieniuk says the widespread idea that the general populace should be opposed to climate policies because it will harm their retirement savings is misplaced.

“It’s not untrue that some wealth is at risk, but in affluent countries, it’s not a reason for government inaction because it would be so cheap for governments to compensate that.”