A group of the country’s biggest miners and local energy companies have agreed to end the feudal approach to the energy system in one of the world’s richest mining provinces, and plan to work together to create what could be one of the world’s biggest renewable energy hubs.

The remote Pilbara region in the north-west of Western Australia is rich in iron ore and other minerals, but the companies that created the huge mining provinces that have delivered tens of billions of dollars in profit, and created the country’s two richest families, have done their own thing.

They have built their own mines, their own roads, their own towns, their own rail lines (sometimes running next to each other) and – in some cases – their own electricity grids.

Now they have concluded that this feudal-style grid system is no longer suitable – and that it’s a much smarter idea to work together and share their grids to cut costs, and lower emissions by facilitating the construction of wind, solar and storage.

The WA government is hailing the agreement on common use electricity infrastructure in the Pilbara as a “landmark” that reflects the push for more renewable energy use in the region.

“This is a landmark agreement for our clean energy future and the economic development of the Pilbara and our state,” said energy minister Bill Johnston.

“This agreement is a historic accord between government and key industry players in the Pilbara, recognising that to reach our ambitious decarbonisation goals common use electrical infrastructure is key.”

Those involved include global mining giants BHP and Rio Tinto, oil and gas majors such as Woodside, BP, and Atco, and local energy groups such as Horizon Energy and Alinta.

It also includes Fortescue Metals and Roy Hill, owned by the country’s two richest families – the Forrests and the Rineharts – who are about as wide apart as is possible on the use of fossil fuels and the benefits of renewables. (Andrew Forrest is an avid supporter of the green energy transition, Gina Rinehart is not).

However, iron ore miners – no matter what their views and political and environmental t-shirts – are all part of a global supply chain where low emissions is now critically important.

Most big miners are looking to rapidly cut emissions at their operations, including through renewable power and storage, and the replacement of diesel trucks with battery electric vehicles.

Johnston says members of the round table group met four times in the past year to reach agreement on future electricity demand scenarios, and the common use framework, which will ultimately see all the different networks linked together.

This is considered essential in the shift to wind, solar and storage, and will enable partners and system security in a shared grid.

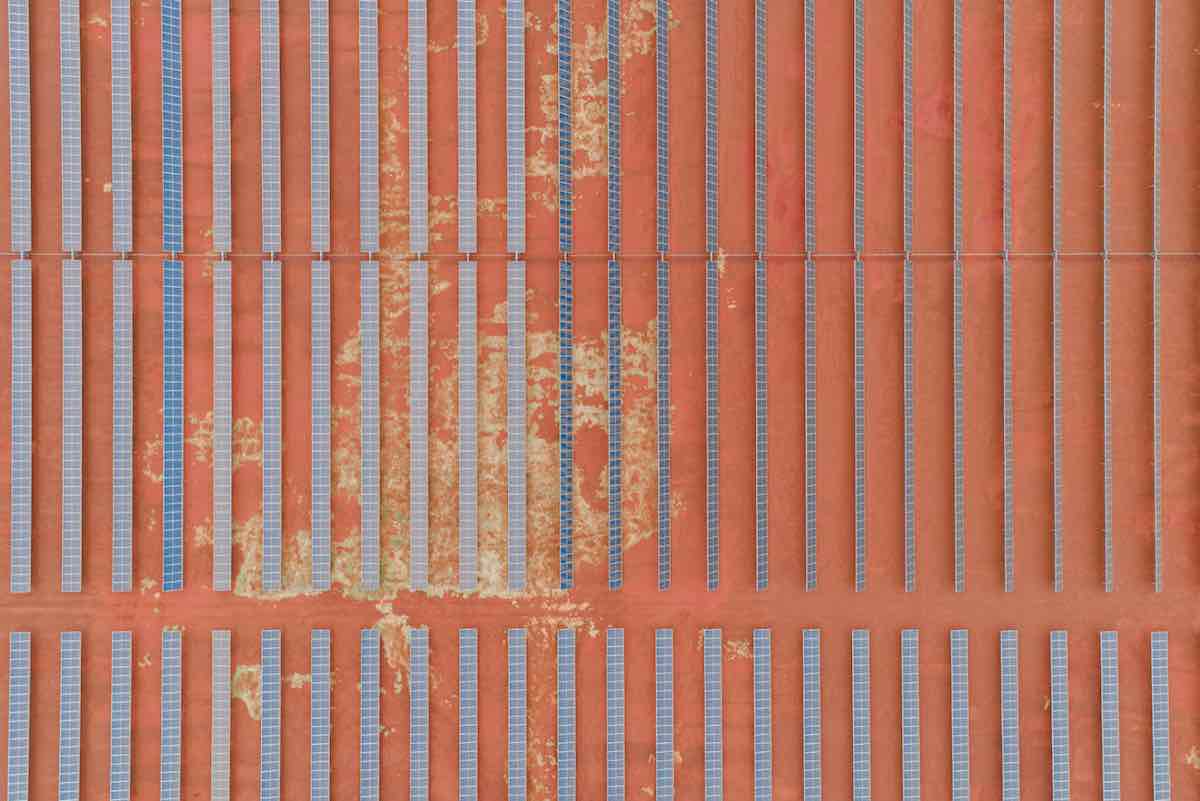

Right now – despite some notable developments such as the first solar farms at Chichester (60MW) and Gudai-Darri (34MW) – renewables make up just 1 per cent of the total electricity generation in the region, which has a peak demand of around 2.2GW.

That demand level is around half the size of the main grid in WA, the South-West Interconnected System centred around the population centres (which is now 35 per cent renewables), and around two-thirds the size of South Australia (which is now 70 per cent renewables).

That 2.2GW will increase significantly as the huge mines electrify – Fortescue is already installing 3MW charging stations for its electric haul truck fleet – and demand will increase again as the region eyes huge renewable hydrogen opportunities.

The roundtable has apparently done its own modelling on the demand forecasts, but this has not been released.

However, BP and Macquarie Group’s involvement in the roundtable – they are both significant shareholders in the Australian Renewable Energy Hub – gives some indication of the potential demand scenarios.

AREH is proposing to build 26GW wind and solar in the Pilbara to supply domestic customers, such as the Pilbara miners, and create green ammonia and hydrogen for domestic use and export. Other groups also have multi-gigawatt renewable plans, including Fortescue and Rio Tinto.

The transformation of Western Australia from a state that, a decade ago, opened the country’s first large-scale solar farm, and then promptly declared its hope to never open another one, to a state that hosts what is effectively the world’s biggest micro-grid and is preparing for the exit of coal, is quite remarkable.

A recent demand assessment report by the state government looked at the possible need for more than 50GW of new wind and solar capacity in the state to support the growth of green industries, and massive new demand from green manufacturing, ammonia and hydrogen hubs.

The work in the Pilbara won’t be easy, however, given the complexity of marrying the individual networks and creating a new system operator, and keeping individual projects running and their owners happy in the meantime.

Johnston says the findings of the Roundtable will be used to design the next phase of work in consultation with industry stakeholders, Traditional Owners and with the federal government and its $20 billion Rewiring the Nation initiative.