Financial losses caused by stranded oil and gas assets could top US$1.4 trillion (A$1.96 trillion), with most of these losses hitting private investors, including retirement savings, new research suggests.

Researchers, led by economist Gregor Semieniuk of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, have assessed the prospects of almost 45,000 oil and gas assets around the world, tracing the potential financial implications of stranded assets through their corporate structures to identify which investors will ultimately lose out.

“We calculate that global stranded assets as present value of future lost profits in the upstream oil and gas sector exceed US$1 trillion under plausible changes in expectations about the effects of climate policy,” says the research paper, published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

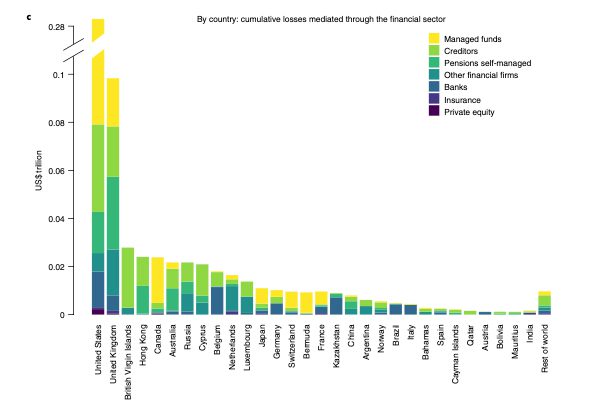

“Most of the market risk falls on private investors, overwhelmingly in OECD countries, including substantial exposure through pension funds and financial markets.”

“Rich country stakeholders therefore have a major stake in how the transition in oil and gas production is managed, as ongoing supporters of the fossil-fuel economy and potentially exposed owners of stranded assets,” the paper adds.

The researchers examined the financial consequences of global efforts to decarbonise energy use would top $US1.4 trillion over the next 15-years.

The assessment is based on ‘plausible’ climate policy responses, including scenarios prepared by the International Energy Agency that detail the significant declines in oil and gas use that must be achieved to limit greenhouse gas emissions to safer levels

The researchers say that growing pressures to decarbonise global energy systems are prompting investors to “re-align” their expectations for oil and gas demand, along with the expected revenues generated by oil and gas assets – leading to an anticipated $1.4 trillion devaluation of oil and gas investments.

Around US$1 trillion of these losses are expected to hit share markets, with the remainder impacting other private investors and governments.

These losses would flow through to retirement savings, with researchers estimating that around US$282 billion could be wiped out from pension funds globally.

The paper estimates that Australian investors would stand to lose a combined US$21.7 billion (A$30.44 billion) through stranded oil and gas assets, including a US$9.2 billion (A$12.9 billion) hit to retirement savings.

Australians hold around $3.4 trillion in combined superannuation savings – the bulk of which is invested in share markets.

The prospect of a declining fossil fuel industry is becoming a major challenge for Australian investment managers, a situation reflected in the researcher’s findings that a much larger proportion of Australian stranded asset losses would impact retirement savings.

This week, health and community service sector superannuation fund Hesta announced that it would back a push led by Atlassian co-founder Mike Cannon-Brookes to reject a proposed demerger of energy giant AGL Energy.

Cannon-Brookes has rallied against the AGL split, which would see the bulk of the company’s coal and gas generation assets carved out into a separate business, arguing the demerger would ultimately slow AGL’s transition away from fossil fuels.

Hesta holds a 0.36 per cent stake in AGL on behalf of its superannuation members, which it will use to vote against the demerger proposal, alongside Cannon-Brooke’s own 11.28 per cent stake.

The research paper focuses on the potential impacts on oil and gas industries and does not include an assessment of coal assets, which represent a sizeable portion of Australia’s fossil fuel industries.

Semieniuk said governments could face increased pressure to bail out fossil fuel industry investors. In countries like the United States, these investors are predominantly made up of wealthy individuals who may attempt to use disproportionate political influence to delay a transition away from fossil fuels.

“Wealthy stakeholders have a larger stake in how the transition to renewable energy is managed than the geographical distribution of fossil-fuel production suggests, both through their support of the fossil-fuel economy and through their potential exposure to stranded assets,” Semieniuk says.

“Decarbonisation efforts by countries in which these stakeholders are based may therefore be more effective in reducing oil and gas supply than previous research might suggest.”

“For instance, policymakers could work with investors to lower capital expenditure of oil and gas companies rather than simply divest, transferring ownership to other, perhaps less responsive parties.”

“On the other hand, expectations of government bailouts of financial companies in these wealthy countries could also lead to perverse incentives for increasing over investment and reaping the dividends while they flow.”