The Australian Energy Market Operator is to model a range of scenarios that include a zero emissions grid by 2035, at the same time as much of the nation’s transport and other energy uses also turn electric.

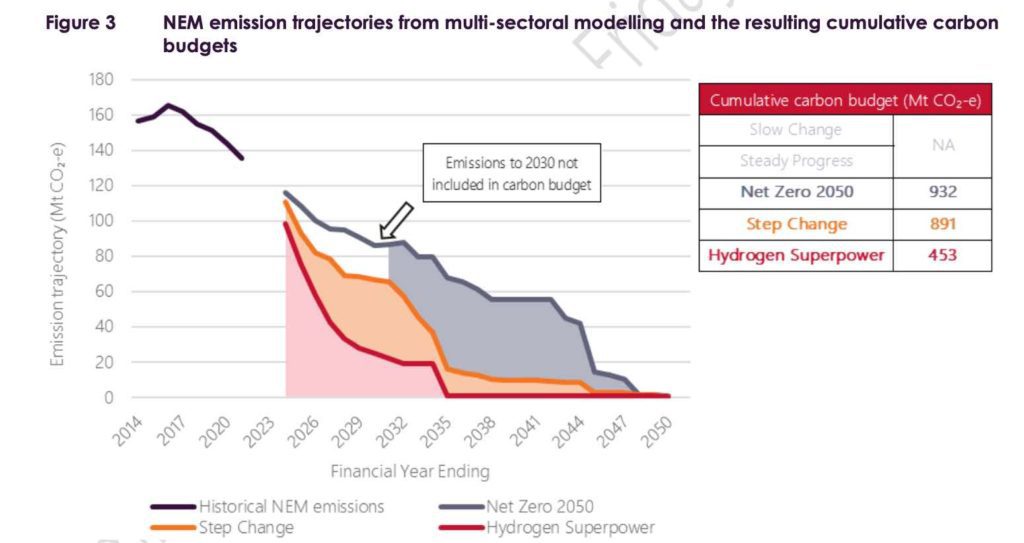

The scenario, known as Hydrogen SuperPower, is one of five created by AEMO as part of work on its Integrated System Plan, its 20-year planning blueprint. But this scenario is the most important because it is the only one that is consistent with global efforts to limit average global warming to 1.5°C.

It assumes that grid emissions fall to zero by 2035, meaning no burning of fossil fuels for electricity, a huge increase in wind and solar, including rooftop installations, batteries, and the end to sales of new petrol and diesel cars.

The five scenarios created by AEMO lay out the stark choices facing Australia – ranging from a rapid transition with investment, jobs, lower emissions and lower energy prices, to bleak outcomes where fossil fuels prosper but little else does.

Another scenario, Step Change, is similar to AEMO’s previous work, and models zero emissions in the main grid by the early 2040s, and is consistent with average global warming of 1.8°C.

The other scenarios are less appealing for those who want to try and avoid catastrophic climate change. Even the Net Zero 2050 scenario is only consistent with a 2.6°C of warming, which highlights just how far Australia’s political discourse needs to move.

The “Steady Progress” scenario models current policies, and also assumes a 2.6°C outcome, which also underlines how a pledge to net zero by 2050 – should it ever be made by the current federal government – would barely shift the dial on climate outcomes.

The Slow Change scenario, representing a go-slow on climate and energy policies and economic growth, delivers a disastrous 4°C outcome. It more or less suggests that society, or at least politicians, have given up on trying to avert dangerous climate change, and fossil fuels continue to be burned.

The scenarios form part of 1,000 pages of a report known as the Inputs, Assumptions and Scenarios Report that will form the basis of AEMO’s next ISP, due next year, which delivers a blueprint of what is needed to manage the renewables transition.

“There is no doubt the energy transition is forging ahead. We have tried to capture this through a range of scenarios characterised by the growth of electricity demand and the pace of decarbonisation,” AEMO’s chief systems design officer Alex Wonhas said in a statement.

“The other, ‘net zero’, is driven by accelerating technology-led emission abatement based on extensive research and development, policy and progressive tightening of emission targets to meet an economy-wide net zero target by 2050.

“We have also mapped out a progressive ‘hydrogen superpower’ scenario based on a power system to support the development of a renewable hydrogen export economy.”

But the first key graph is this one above. It shows how the grid needs to reach zero emissions by 2035 for the Hydrogen Superpower scenario and if Australia is serious about delivering on the Paris climate target of 1.5°C.

This, of course, means no coal generation, and – in contrast to the federal government’s “gas-led recovery” narrative – there will no room for gas (apart from maybe a handful delivering emergency back-up if needed).

The ISP will go into the details of what that means in terms of new wind and solar projects, plus energy storage and the infrastructure and the grid services needed to support it.

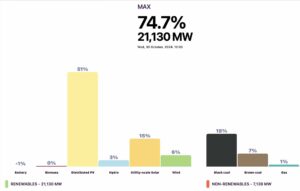

That will no doubt create an engineering challenge. As AEMO boss Daniel Westerman admits in this week’s Energy Insiders podcast, AEMO is not yet sure how to reach 100 per cent renewables for even short periods, although it intends to learn how to do it by 2025.

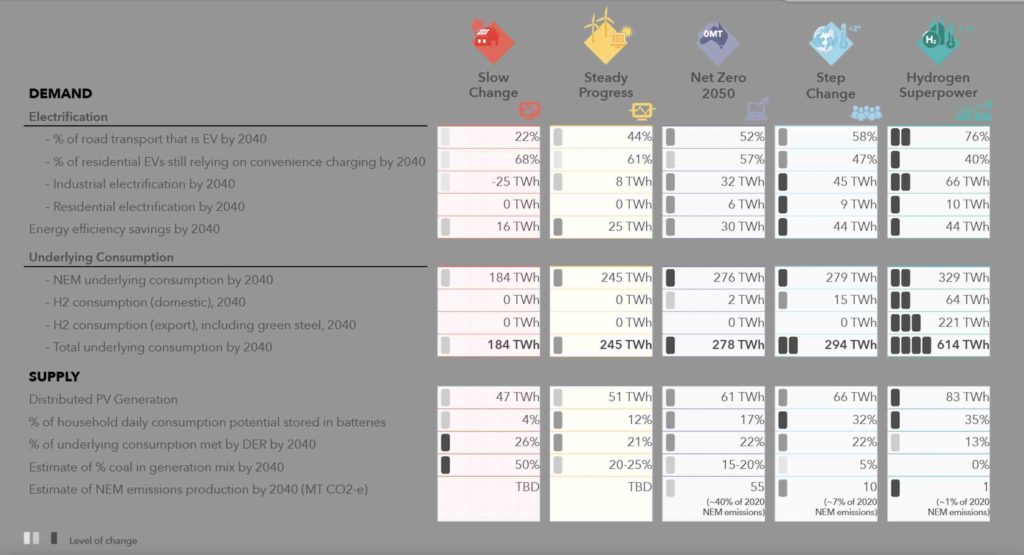

But to give a hint of what the Hydrogen Superpower scenario might involve is this next table, which assumes that by 2040 the level of electricity demand has trebled, thanks to the level of electrification and the power needed to deliver the renewable hydrogen.

There are some other key points to note of the Hydrogen scenario, including the 76 per cent share of the road transport fleet being electric – which must mean that new petrol and diesel car sales are phased out years earlier.

Electrification of homes (heating and cooking) and industry has multiplied, effectively kicking out gas, leading to a big increase in electricity demand. Some 45GW of battery storage soaks up one third of output from an estimated 80GW of rooftop solar PV.

And to support the displacement of LNG through green hydrogen exports, including the development of green steel, total electricity consumption trebles to around 614 terawatt-hours.

And, of course, most of this demand needs to be met by wind and solar. It doesn’t say how much, but one assumes it will require the sort of massive renewable hydrogen projects being contemplated by the likes of Andrew Forrest and CWP Renewables, and others, although this study is focused on the National Electricity Market, and not events that may unfold in the west.

To top it off, the modelling assumes that the Hydrogen Superpower scenario, the one that delivers on climate targets and supports the most new investment, also delivers the cheapest power prices for customers over the medium to long term.

Contrast this with one of the so-called “central scenarios”, the Steady Progress based on current policies that delivers a painfully slow transition to EVs, and leaves coal delivering a quarter of grid supply.

The Net Zero 2050 scenario delivers higher shares, but most of this comes after 2030, so misses many of the essential gains from an early cut to emissions.

The fine details of how this plays out will be delivered in the ISP – with a draft due in December and a final report in the middle of next year. One hopes that it will be given more respect from the government that the last ISP, which was mocked by federal energy minister Angus Taylor as “lines to nowhere”.

At least some of the key state governments are already on board, with stated aims of harnessing enough wind and solar (for the purposes of green hydrogen) that represent two times (Tasmania) or even five times (South Australia) the amount of power currently consumed.

The Hydrogen Superpower scenario is exciting, if a little daunting given the scale of what must be achieved in the next decade and a half.

The central scenarios – steady progress and net zero 2050 – are important for developers and financiers and the like, because they form the basis of risk assessment and financing decisions. It limits the deployment of most capital to a scenario that assumes 2.6°C of warming, with the catastrophic outcomes that that might entail.

But the most depressing aspect are the first two scenarios, slow change and steady progress. Australia seems to find itself stuck between the two, despite the enormous potential for the transition. The biggest impediment to change is politics. Or ideology.