Origin Energy’s returns have been every bit as bad as AGL’s over the past 12 months – and over the past three years. Over three years, the share price has halved. In AGL’s case, it’s taken a few years for the mirage that the Hazelwood closure caused to fade – and it’s fading – revealing the futility of going big in coal generation.

In Origin’s case, it’s more of a slow death of falling gas prices and the inability to establish a steady growth business in almost any area. One minor but important exception is Community Energy Services, where gross profit is now up to $75 million a year.

For the record, I recommended Origin (ORG) as a buy during much of the APLNG construction. And I was wrong. It’s one of at least two sharemarket calls that I regret. Act in haste and repent at leisure. That said, the share market performance of both companies suggests that investors should treat whatever statements management makes about their strategic competence with a degree of caution. Neither has shown any ability to make money for investors over the past decade.

Within Australian utilities, the best place to have been invested in the past decade is in electricity and gas distribution and gas transmission.

Neither AGL or ORG have so far shown any desire to really embrace decarbonisation as opportunity. They have chosen to ignore the low cost of wind and solar for the supply of bulk energy; failed to realise that their scale could have given them comparative advantage in that area, and instead focused on defence. Defence of thermal positions, defence of retail market share.

The one exception is ORG’s investment in, and commitment to, Octopus/ Kraken; a modern software environment. ITK thinks the Octopus/Kraken path is fraught with danger, but nevertheless it shows ambition. APLNG is, in the most generous view, a fixed-term annuity, moving to the point where net present value will start to decline. Every year of low gas prices is essentially a loss of 5% of reserves for nothing. The APLNG cash flows have to be used to secure ORG’s future. Octopus is an interesting start. ORG’s gas retailing business has good market share but no realistic long-term growth prospects.

For both AGL and ORG it may be that they are “cheap,” or it may not. What’s become clear to me, though, is that if you want long-term commitment from investors, you have to show them a genuinely sustainable business in the broadest sense. Preferably one with some growth.

AGL will need to reconfigure itself to do that. Origin needs to make up its mind. It has neither the strong market share that AGL has in generation, nor the “green flavour” that someone like Neoen or Snowy or Cleanco has, or any of the small green retailers. In short, it’s seen no advantage from its “generation-lite” focus. Equally, ORG talks decarbonisation talk, but does little or nothing beyond keeping up with sector.

Origin Energy performance and strategy

Compared to AGL, ORG only owns one coal station and it’s made no bones that it will close that no later than 2032 (when its current ash dam is full). However, we note that ORG invested more than $1 billion in Darling Downs gas power station, about $500 million in Uranquinty (gas), and more than $650 million in the Mortlake gas power station. ITK would argue that ORG has to struggle to earn weighted average cost of capital on its gas-fired generation.

Is ORG’s wholesale energy cost competitive?

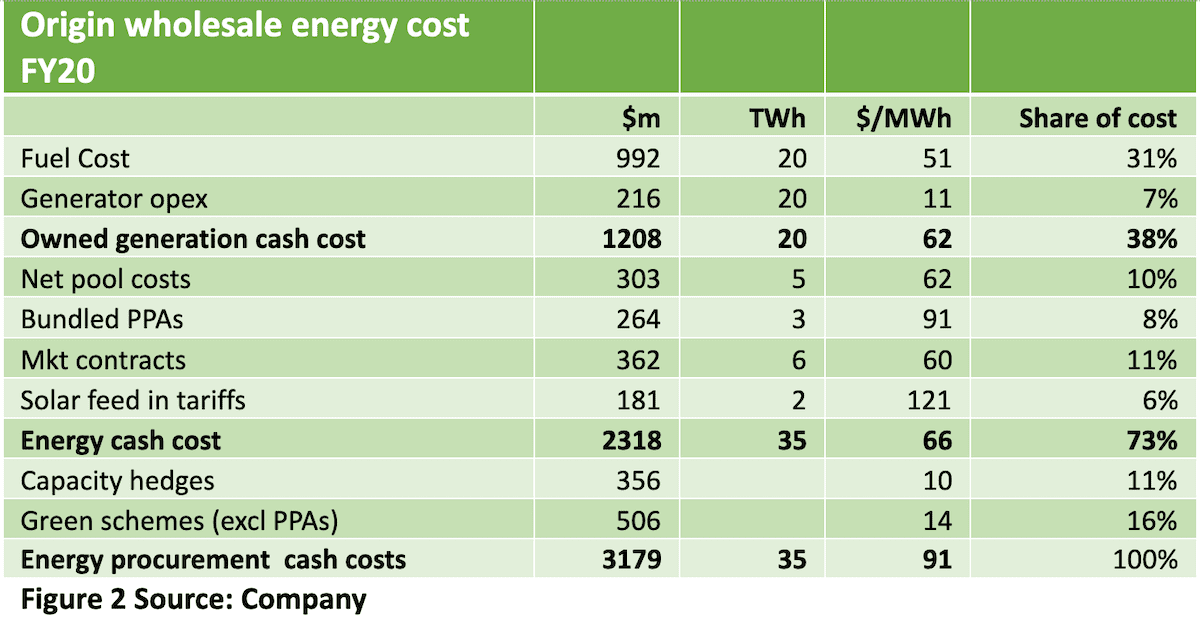

ORG’s disclosure is useful. We think it’s useful for management that they provide the same information to the market as they see, themselves. In any event, in FY20 ORG split out its bundled PPA cost from its market contracts in showing its wholesale energy cost build up. There is a lot to think about in this table.

ORG is paying $91/MWh for its bundled PPAs. That’s clearly out of the money in today’s world and should come down materially if Stockyard Hill (which, by my reckoning, has taken longer to build than APLNG) ever actually produces anything.

At today’s PPA prices, a wind or solar developer would be confident of undercutting the $60 generation cash cost (and that will rise as gas prices recover).

However, the questions I ask myself are:

- Could a new entrant with a large market share and a focus on green energy have a lower cost?

- Could ORG do better?

I tend to think the answer to both questions is yes, even after adjusting for today’s fuel and market prices. However, other than noting that no such potential new entrant (AGL version 12, anyone?) exists today, I’ll leave that to chew on later and do no more than note that a 100% renewable gentailer could get a bundled PPA at $50 or less and definitionally avoid most of the extra green scheme costs, but would incur more capacity hedges and some firming costs.

Can moving to a platform change the competitive position of either AGL or ORG?

This is a vital question for both, but clearly ORG thinks it can. ORG has invested roughly $570 million for a 20% stake in Octopus, a leading new entrant retailer in the UK and now with operations in Japan and a system in Australia.

More importantly for this discussion, ORG will pay Octopus an additional $100 million for Octopus to convert ORG’s sales and marketing computer software to Octopus’ platform, Kraken. The implementation costs at time of announcement were to be spread over four financial years, with the bulk in FY22 and FY23.

At the time of the announcement in May 2020, eventual savings were targeted at, say, $125 million per year from FY2024.

What is Kraken? Kraken is a platform built on modern software buzzwords; Agile computing, Scrums, Django, Python. In my as-usual amateur opinion, the software is characterised by being open source and deployed rapidly. Please see glossary for a few concepts. As far as I can tell, it’s a culture as much as a system. Historically, ORG and AGL have outsourced customer care systems and other retail software to consultants. For instance, AGL uses Accenture and I think Origin used Wipro.

What is a platform? Platform economics were new to me as a theory, even though I’ve watched them in action for many years and even though markets are platforms. So I went out and read a textbook.

In my words, a platform company is a business that provides a way for groups of buyers and sellers, producers and consumers, to meet. Paypal which has a market cap more than double the Commonwealth Bank and grew 30% in 2020 would be a typical example, alongside even more famous brethren Uber and Airbnb.

So, outsourcing customer care and other software means losing control of what should be the core competency of an energy retailer. It also means lots of sand in the gears in terms of responsibility, speed of change and all the other things that agile development as a culture is supposed to avoid.

Probably for ORG there will be more than 20 major packages involved with some of the functionality existing on servers and some of it in the cloud and some of it on devices.

Unlike the UK, the ability of customers to interact with the platform is very limited. That’s because about 50% of ORG customers are in NSW, where communicating meter penetration other than for solar systems is only about 15%. And it’s no different in Queensland.

And, of course, Australia is not just Australia; it’s NSW, Victoria, Queensland, etc. Each of these regions have separate requirements. For example, Victoria has a different default tariff regime.

In one sense, all ORG is doing is changing from one outsource provider to another. The question is whether it’s more than that.

Assuming the process goes well, we expect ORG management to gradually open up about what is involved and the benefits. So far, ORG appears to be operating in accordance with the current best practice paradigm of establishing a standalone business (‘Retail X’) to undertake a buildup of ORG’s business model. In accordance with Agile philosophy it builds a “minimum viable product” (MVP). Presumably this standalone business already has been handed some customers. After that it scales, iterates and grows a life of its own.

If ORG’s model is shown to have competitive advantages, the other gentailers will follow. Definitionally, Kraken is never finished and never complete. Almost certainly the packages on the platform will continue to evolve and the present buzz is machine learning.

Will users buy into the platform? Will there be many generators?

Take the example of Apple. Apple offers its core apps and provides a platform. Many developers provide products and services through the app store?

Is this concept transferable to an energy gentailer? Even if we assumed away the technology issues, i.e. lack of communicating meters, there so far hasn’t been any suggestion of allowing any generators other than distributed solar onto the platform.

In fact, as I argue below, it’s really the network that is the true platform business, or would be if it had a platform mindset.

Moving to Kraken might lower ORG’s costs but the question is, can it enhance revenue? How could that actually happen? By selling more products, as AGL is trying to do? By encouraging consumers to consume more? By attracting a bigger market share? All are possible, I suppose.

What will attract consumers to the product? Many platform business have been successful because they offered access to one side, typically consumers, for free. Alternately they provide some service or functionality to consumers that they didn’t have before. For instance Paypal let small merchants without credit card authorisation facilities accept payments.

What is an energy retailing platform going to provide? I would think it’s going to have to be something more than “100% green” or “carbon neutral,” as every retailer will offer that shortly. My underlying point is that ORG starts at a cultural disadvantage; it’s perceived as an old school gentailer dependent on coal and gas. In fact, its philosophy – until the law changed – was to keep customers on default tariffs as long as possible. Changing that culture internally is hard enough, changing the external perception of it is even harder.

Is a retailer the “right” organisation to operate the platform?

In the real world, in real time, there isn’t really a question of better or worse, there are just winners and others.

Nevertheless, if I operated a wires and poles network I would think I had a huge comparative advantage in platform markets. I would think that there are economies of geography that exceed economies of scale and, in any case, as a network business I have scale. I would think it is much easier to add metering functionality at my cost of capital, I could add community batteries and I could build community platforms that would be naturally attractive to users. I could add resiliency functionality and aggregate demand and supply responses.

However, it’s cultural. At the moment, it doesn’t seem like there is one wires and poles network in the country that thinks of itself as anything other than a regulated monopoly.

AGL: A good time or a long time? Lowest-cost thermal generation is AGL’s biggest problem

AGL has, by common consent, the lowest variable cost thermal generation in NSW, Bayswater; and in Victoria, Loy Yang A.

Controversially, ITK sees that this may be more of a problem than an advantage. The low-cost position tends to dampen the signal the market is sending, that coal generation is under sustained long-term pressure.

It’s kind of like being the Blackberry or Nokia of the phone industry when smart phones were introduced. The advantage makes you blind to the need to change.

Not that anyone can accuse AGL of being blind. Not now. In fact, in my humble opinion Brett Redman spoke better at the results about what customers want and how to think about that than most in the industry I’ve heard talk. We’ll come back to that.

What to do?

It’s a bit ridiculous for an ex-analyst to presume to suggest how AGL can maximise investor value. In our view, the best opportunity to maximise value passed years ago, when AGL abandoned its wind investments and switched to thermal generation. Few now remember that Michael Fraser, past CEO of AGL, now chair of APA and on whose watch the thermal investments were made, was also chair of the Clean Energy Council and that AGL was once the largest, or close to the largest, renewable developer in Australia.

That said…

Et Tu, Brute? AGL has many opportunities

We still think there are still plenty of opportunities. In the end, over $US3 trillion of annual global point-of-production revenue of coal, oil and gas – never mind the downstream revenue from electricity, etc – is going to go away, mostly over the next 25 years, and be replaced by alternatives. If management can’t find something to do to be a winner in that context, then perhaps they, too, should consider becoming ex-management.

ITK has previously drawn attention to the example of Orsted, a privatised Danish government company that used to do thermal generation and is now one of, if not the largest offshore wind developers in the world. In ITK’s opinion, there is still enormous scope to do offshore wind development in Asia. South Korea and Japan are two obvious markets and presumably India offers opportunities. However we doubt that AGL has the culture or ego to assume it can be a successful offshore wind developer. In truth, it would be a heck of a risk. In ITK’s view, though, the prospects of someone making a good return on capital from offshore wind in Asia are far better than those of the many speculators building hydrogen spread sheets.

Secondly, AGL could perhaps decide to be a firming supplier, like Snowy Hydro. This doesn’t, in our view, mean running the coal plants as if they were coal plants. Rather, it means sponsoring lots of wind and solar and using the coal and gas plants to differentiate the service from those suppliers that are more price takers. It would be the same course as taken by, say, Infigen but starting from the other end.

Thirdly, in line with ITK’s prior thought bubble, we think it’s open to AGL to split itself in two. Shareholders get a share of Retail Co and a share of Thermal Co.

Retail Co, in our thought bubble, has the customer accounts and the supply contracts with the wind generators; it also gets Southern Hydro. Retail Co is lightly geared and gives Thermal Co a supply contract, with declining volumes over the next few years.

Thermal Co gets the thermal assets, most of the debt, and a supply contract to Retail Co. Thermal Co runs its coal assets and has a gradually declining contract with Retail Co, sufficient to provide enough cash flow to cover the majority of its debt.

Thermal Co also needs to generate enough surplus cash to cover its clean up, but can use the option provided by transmission to power station gate to do its batteries, or whatever.

In ITK’s very amateur view, the major issue is cultural. The main reason for separating out the thermal assets from the other is that Retail Co can have a total buy-in to decarbonsiation and to new ways of retailing. And that brings me on to Origin.

Glosssary

Multi-sided platform: A business that operates a physical or virtual place (a platform) to help two or more different groups find each other and interact.

Two-step strategy: An ignition strategy in which the platform secures significant participation by one group and then secures participation by the other group by offering them access to the first group.

Scrum: One of the agile methodologies designed to guide teams in the iterative and incremental delivery of a product. Often referred to as “an agile project management framework,” its focus is on the use of an empirical process that allows teams to respond rapidly, efficiently, and effectively to change. Traditional project management methods fix requirements in an effort to control time and cost; Scrum, on the other hand, fixes time and cost in an effort to control requirements. This is done using time boxes, collaborative ceremonies, a prioritised product backlog, and frequent feedback cycles. The involvement of the business throughout the project is critical, as Scrum relies heavily on the collaboration between the team and the customer, or customer representative, to create the right product in a lean fashion. Scrum was developed as a concept in about 1995.

Agile: Agile is the ability to create and respond to change. It is a way of dealing with, and ultimately succeeding in, an uncertain and turbulent environment. From a 2001 conference came the “Agile Manifesto” with 12 principles. Agile appears to be a philosophy of continuous development with the higher priority being to satisfy the customer through early and continuous development of valuable software. Business people and developers work together daily and projects are built around motivated individuals. ITK foot note: Since my whole career (in broking research and now consulting) was built around similar concepts, it’s hard for me to get excited, but I do recognise it’s not how software was done historically..

Django: A free opensource high level Python Web framework built around the actually not-so novel idea of reusable modules. Python is a modern computer language now very widely used, deceptively easy to learn.