Australia is in the midst of an unprecedented, albeit heavily delayed, renewable investment boom – one that may not be repeated on this scale and in such a short period again.

The fact that this is coming to an abrupt end – given the lack of any coherent energy policy from the federal government – is no secret. But the budget entries for the Clean Energy Finance Corporation provide the first tangible evidence.

The $10 billion CEFC has told the government that it will need to draw down just $530 million from its special account in 2018/19.

That number itself is not unusual: It signalled a similar sum – $550 million – at the same time last year, but it ended up drawing down $2 billion because of the surprising level of investment in renewable energy projects.

The fact that it has not upped its request this year (as it had the previous year when it drew down three times its initial request) is being taken as a sign that the boom in renewable energy investment – at least at large scale – is well and truly over.

There are several tell-tale signals. According to the Clean Energy Regulator, and private analysts, the 33,000GWh renewable energy target for 2020 is basically already met, and most likely exceeded by the number of projects built and under construction.

The signals for future investment are not so great. Victoria is holding an auction for 650MW of wind and solar, which has attracted 3,500MW of bids, and will seek more as it build out its legislated state target of 40 per cent by 2025.

Elsewhere, Queensland has a 50 per cent renewables target, but not much has been heard of that in the last little while, and the Northern Territory is in no great hurry to acquit its 50 per cent renewables target anytime soon.

That leaves the only the corporate sector for large scale renewables. Sanjeev Gupta is promising to build 1GW of solar and storage to help power the Whyalla Steelworks, but many other corporates may simply contract with existing wind and solar farms.

A huge 9GW wind and solar project is proposed for the Pilbara – but this will depend on both corporate off-take agreements in the region, and contacting from customers in Asia. (You can hear out podcast interview with project partner CWP here).

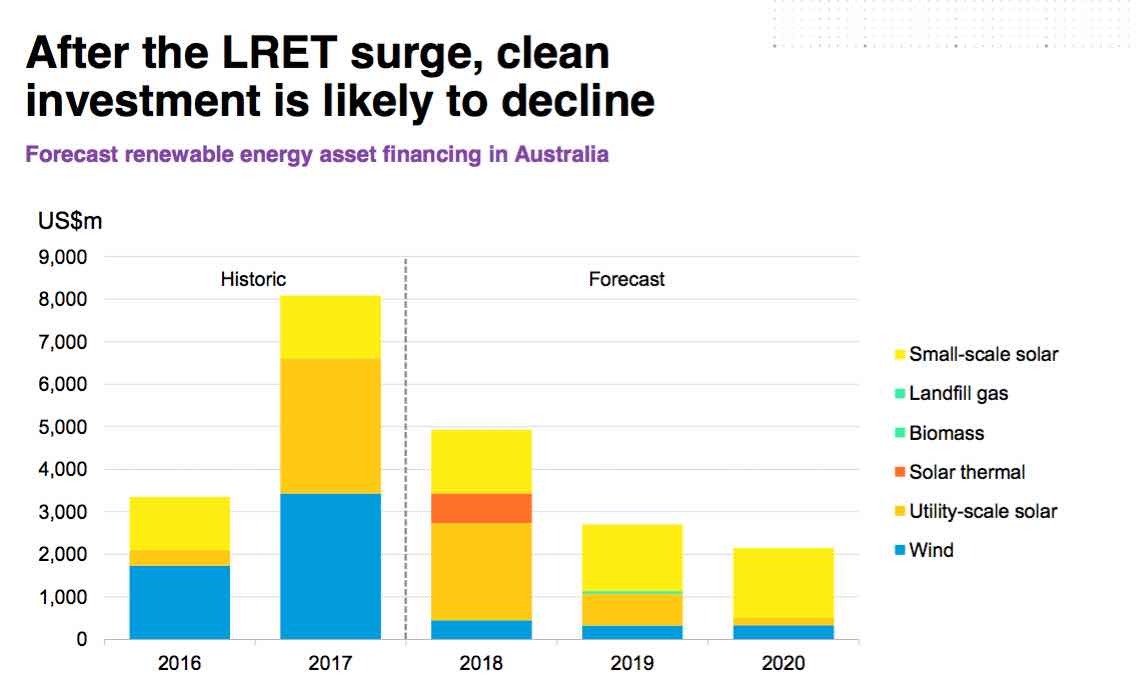

The boom/bust scenario is highlighted by this graph above from Bloomberg New Energy Finance, which suggests that any remaining investment in the years out to 2020 will be dominated by solar.

Worryingly, it suggests that unless the federal government lifts its emissions reduction target for the electricity sector – currently at just 26 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030 – then the proposed National Energy Guarantee may actually strangle new investment.

This graph below shows that business as usual suggests only a modest increase in investment from 2020 to 2030, but with the NEG – under current government emissions targets – renewables would be less.

The only sectors that continues its boom, is the behind the meter or small scale solar sector, which will jump from around 7GW now to 19GW by 2030 – suggesting an annual run rate of 1GW for the next 12 years. Gas is also seen to benefit from the NEG.

Labor seized on the CEFC budget measures as a sure sign that there will be a dramatic fall in renewable investment as the country transition from the RET to the NEG. (Ed: Retnegs?)

“Few know the Australian renewables industry better than the CEFC, and this is an ominous sign of an industry getting ready for Malcolm Turnbull’s weak NEG,” Labor’s Mark Butler said in a statement.

“Under the current weak emissions reduction target of the NEG, analysis has shown there will be no new large-scale renewable energy projects built for the entirety of the 2020s.

“Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberals continue to wage their war against renewables to appease the hard right climate deniers of the Coalition party room.

Butler pointed out earlier this week the fact that Australia is already missing out on a renewables job boom – despite the strong investment in the last year, suggesting that the country could have twice as many jobs in the sector, and more investment, with consistent policy.

The pace of the renewables investment boom caught most people by surprise.

After languishing in an investment drought for three years after the election of the Abbott government, as the Coalition sought to repeal and then cut the RET, the floodgates opened and enough capacity has been built and committed to meet the new target two years early.

In fact, some suggest there will be enough capacity built by 2020 to meet the old 41,000GWh target. Renewable energy critics insisted that even the 33,000GWh target would be impossible to meet.

So far the CEFC has made total commitments of $5.8 billion since its inception in the Gillard Labor government – along with ARENA, the now defenestrated Climate Authority, and the defunct carbon price.

The 2017 and 2018 financial years saw a total of more than $3 billion drawn down from the special account, much of it to large scale solar, and wind projects.

But much of its investment now is geared toward energy efficiency, and other clean energy economy investments such as electric vehicles.