The pro-coal and anti-renewable brigade have been quick to pin the blame on renewables for any price spike or supply squeeze on Australia’s National Electricity market over summer.

How frustrating it must be for them that there has not been a major blackout – apart from outages caused by storms in Queensland and local network failures in Victoria. They really, really wanted one to happen.

So it will be interesting to see what they make of events in Queensland this week – the state with the biggest coal fleet that was forced to turn to plants powered by jet fuel, and imports from NSW to ensure the lights stayed on in the middle of their heatwave.

Queensland on Wednesday afternoon hit a record peak grid demand of just short of 10,000MW – and it might have been over 10,000MW were it not for the 370MW of rooftop solar satisfying some household and business demand.

It was the third consecutive day of record demand in Queensland – and extraordinarily the last peak on Wednesday was more than 500MW higher than the previous peak (January, 2017) before this current heatwave.

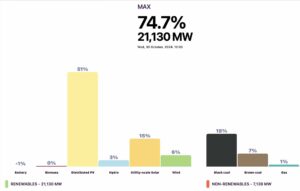

As this graph above shows, the peak would have been even higher without solar, which not only clipped the peak by a considerable margin, but also pushed it later in the day. (Sorry, can’t explain difference between this graph’s estimate of peak demand, and AEMO’s).

Just as well rooftop solar was there, because it appears that at the peak some of the state’s biggest coal generators wound down their output, likely because of heat issues that were putting stress on plant and equipment (as intense heat often does).

Milmerran was operating at just 70 per cent capacity, and there were unexpected outages at Gladstone (the biggest coal plant), and at Braemar (gas), according to the Australia Institute’s Gas and Coal Watch.

All told, analysts estimate the state’s coal fleet was delivering around 1,000MW less than its capacity at the time of peak demand.

This meant that the grid operator had to turn to the state’s considerable combined cycle gas plants and its peaking gas plants, and – as it does on rare occasions -it also called on the Mt Stuart peaking plant that burns kerosene, or jet-fuel.

(See our graph above taken from our excellent new wider, OpenNEM).

Ironically, Queensland also turned to imports to fill the gap between supply and demand, importing 177MW, or nearly two per cent of its needs, from NSW at the time of its peak.

And where might those imports have come from? Most likely from the power generator closest to the border (that’s the way electrons flow), so it would have been the 175MW White Rock wind farm near Glen Innes, in the heart of Barnaby Joyce’s electorate, that was putting out around 140-150MW at the time.

This is not to suggest that the Queensland grid failed in some way. It is to point out that all grids – coal or renewable – struggle to meet such peaks in demand.

And all grids – coal-based or renewable – need back-up capacity to meet those peaks. And all grid, coal-based or renewable – like to export and import to and from neighbouring grids. It’s the way the market is supposed to work.

Mt Stuart, in north Queensland, is one of dozens of such generators that are switched on for just a few hours of the year. It burns kerosene, or jet-fuel in its three turbines, and in the six months to December produced just 3,000MWh of electricity, or about seven hours of production at capacity.

These and other turbines were installed decades ago (Mt Stuart in 1999), long before renewables became a thing. So to suggest that their use in renewables-based grid is somehow a sign of the fallibility of renewables is patently absurd.

It was also interesting to note that during this heat wave, prices in Queensland spiked to more than $350/MWh, while prices in South Australia and Victoria both dipped into negative territory.

The Queensland prices might have spiked more, as they did in last year’s heatwave in January and February, when they regularly hit the market peak of $14,200/MWh, but the state-owned generators are now under strict instructions from the government not to use their market power in such a way.

I guess it’s one of the advantages of state-owned assets. South Australia must be envious.

It will be interesting to see what happens when the current 3GW of large solar and wind capacity, along with some battery and pumped hydro storage, is added to the newly 2GW of rooftop solar in coming summers.