My parents are almost 80 years old and live in Sydney, the place where they were born and raised. Yesterday I phoned them to ask for news of bush fires that are raging just beyond the western edge of the city. As they described the pall of dark smoke that has covered the city of over four million people, I thought of my childhood summers. We knew there would be searing temperatures and days of “total fire bans” when not even backyard barbeques were allowed. But I remember those days being during my summer vacations – that is, in December and January. Now they are happening in October, in springtime.

Right now there are more than 60 fires blazing in the state of New South Wales, where one in three Australians lives. Temperatures are forecast to reach almost 100 degrees F with wind gusts over 60 miles per hour. A fire front almost 200 miles wide is threatening western Sydney.

The authorities have declared a state of emergency, with the situation into its sixth day with little sign of abatement. The Bureau of Meteorology has issued warnings this week that are typical of mid-summer, not spring. And for my parents, they just don’t recall spring conditions like this before. It’s like watching the weather on steroids.

Australia bracing for extreme fire season

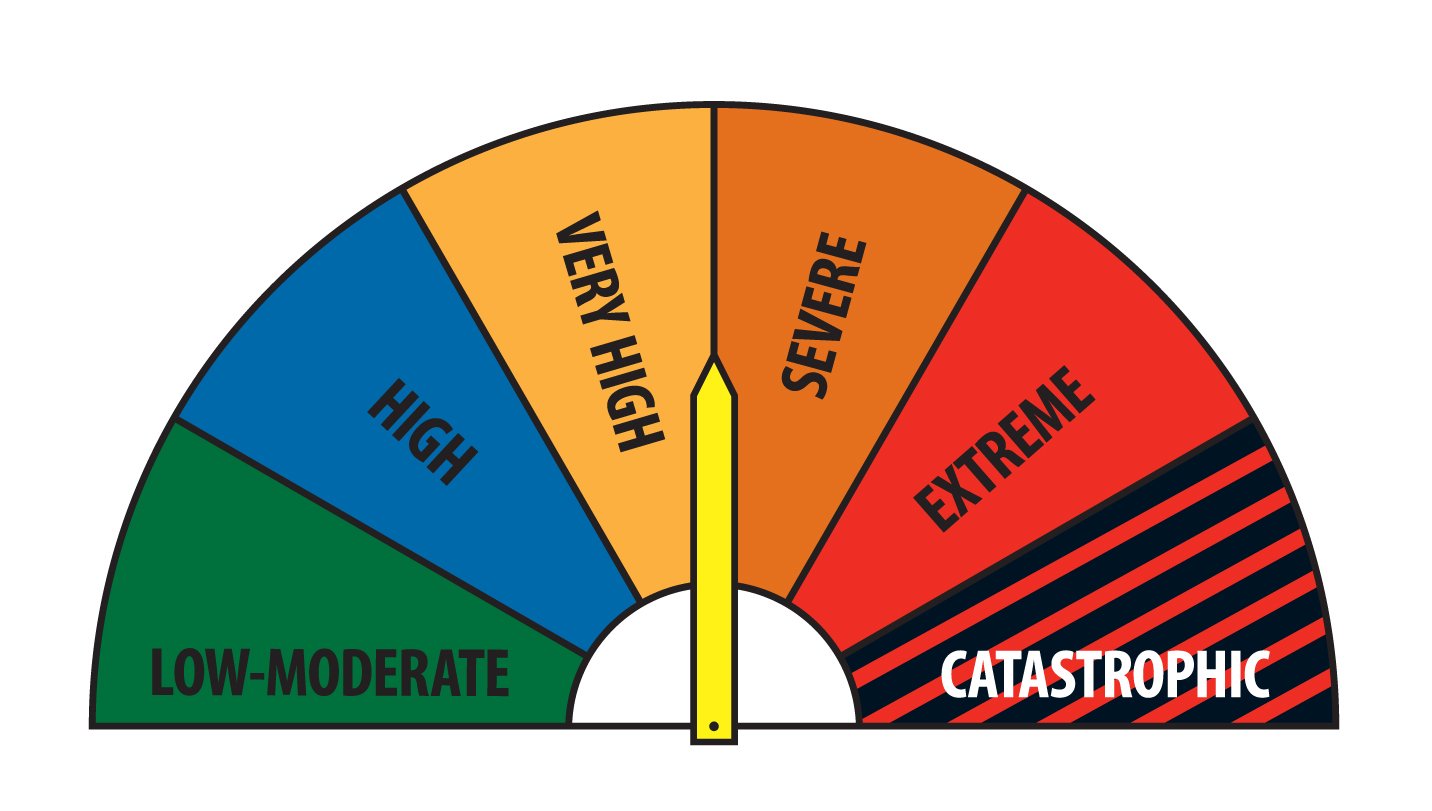

This is the second time this year that the Australian wild fire rating system has risen to “catastrophic,” a designation that was used for the first time during the 2009 Australian fire season. The country has just had its warmest 12-month period on record, its warmest September on record, and has just come out of an exceptionally dry and warm winter.

Similar to conditions the US Forest Service and other emergency responders were facing in the northern hemisphere this spring, Australia is facing a tumultuous start to the southern hemisphere fire season.

The Australian bush fire danger rating scale now includes “catastrophic”. Source: NSW Fire Service

Fire behavior unprecedented

Fire seasons, of course, have great variability from year to year, but both in the US and in Australia experts are saying the fire behaviors they are seeing are unprecedented.

In the western US, fire season is now two months longer than it was 40 years ago. According to the U.S. Forest Service, wildfires are increasing in frequency, intensity, and complexity. Wildfires are twice as large and three times more expensive as they were a decade ago. This past summer saw extreme and unprecedented behavior of fires in Colorado and California. The science is clear that humans have influenced global temperatures over the past half century. And the latest IPCC report states “future warming of extreme temperatures is virtually certain.”

Extreme temperatures, increased wildfire risk, higher costs

The costs of fighting wildfires across the US have averaged more than $3 billion per year, and home protection contributes substantially to this amount. Nearly one-third of what the Forest Service spends each year to fight forest fires goes to resources and manpower to protect homes and structures, equating to more than $1 billion per year. The U.S. Forest Service is increasingly being strapped for funds as the wildfire seasons now lasts longer than it previously did and more people are building homes near forests.

A recent forest study in Oregon showed when the average summertime temperature is just one degree Fahrenheit warmer, the cost of defending these homes doubles. Over the last several years, the Forest Service has used money meant for recreation and land management programs to fight fires. Decades ago, about 20 percent of the forestry budget was devoted to fire. But this last fiscal year, more than half of the U.S. Forest Service budget was spent on fighting wildfires.

With climate change now part of our daily lives, we are witnessing the beginnings of a very challenging problem for emergency managers. It is playing out for us in Australia today.

Melanie Fitzpatrick, a climate scientist with the UCS Climate and Energy Program, is an expert on local and global impacts of climate change. She holds a Ph.D. in Geophysics from the University of Washington, specializing in the role of sea ice and clouds in Antarctica.

This article was originally published on the Union of Concerned Scientists Equation blog. Reproduced with permission