The Tesla big battery has been the big news of the Australian electricity sector since its formal opening at the start of December, grabbing headlines for its many interventions in the energy market and the first-of-its-kind demonstration of the next generation of technologies.

The Tesla battery, formally known as the Hornsdale Power Reserve, is perhaps the biggest development in an industry that has seen little real change in nearly a century – its impact is probably more profound than even the spectacular cost reductions in wind and solar power.

For much of its first weeks of operation, most of the Tesla big battery’s activities were a mixture of tests, trials and just a little showboating – going from zero to 100MW in 140 milliseconds, jumping in ahead of contracted generators to arrest falls in frequency as big coal generators tripped off-line, and just generally being smart and fast.

Some of its early manoeuvres were spectacular but didn’t appear designed to be making money, focusing more on testing its capacities and abilities, particularly its speed of response and reliability, as much for the satisfaction of its builders (Tesla) and owners (Neoen) as for curious third parties.

That phase seems largely complete, and in the midst of the heatwave and the gyrations in supply, demand and pricing last week, it seems that Tesla is now able to demonstrate its ability to cash in and make money for its owners.

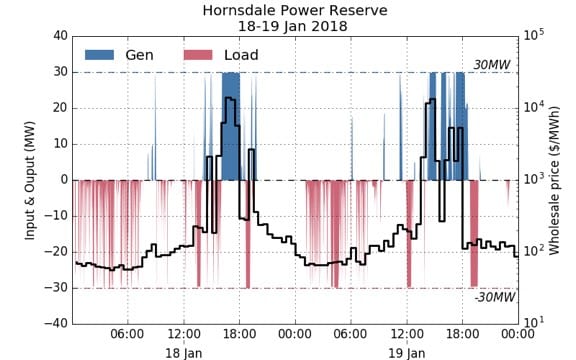

This was particularly visible in the price spikes that hit the South Australia market on Thursday and Friday, as this graph at the top illustrates.

The blue indicates generation, and mostly coincides with high prices, particularly the big spikes on Thursday and Friday afternoons. The red indicates charging, or load, and this occurs mostly during lower priced periods.

Another view of this data is presented below, showing the actual price achieved during the buying (charging) and selling (generation). It’s hard to be sure, but it might have made around $1 million over the two days from the wholesale market.

The advantage of the Tesla big battery over other sorts of storage, and particularly over fossil fuel generation, is its ability to switch on and off in an instant, meaning it is capable of responding immediately to change in demands and pricing.

The Hornsdale operator uses around 30MW/90MWh in the wholesale market as a form of price arbitrage, balancing wind output from the neighbouring Hornsdale wind farms, taking advantage of spikes and dips, generating when supply gets tight, and making micro adjustments to supply and demand.

The rest of the battery – around 70MW, 39MWh – is contracted by the South Australia government specifically to deliver “network” services, such as frequency control at a time of system faults and problems.

Tesla has demonstrated its ability to respond quickly by jumping into the market in other states in recent weeks, such as when the Loy Yang A units failed on repeated occasions and when a unit at the Eraring coal generator in NSW also failed.

It jumped in again, last Thursday, possibly for a little more showboating, or testing, when the Loy Yang B unit tripped and pushed frequency outside its normal operating band.

The fact that the battery focused on network services carries less storage capacity is because the services they provide are usually of short duration – such as arresting changes in frequency within 5 minustes.

Exactly how the contract with the South Australia government works is not clear, like so much of the opaque electricity market – but some insight into its capabilities was given on those same days by its offering to the frequency control and ancillary services (FCAS) markets.

These three graphs above – again from McConnell at the Climate and Energy College, and sourced from NEM data – are a good illustration of how the battery can divide its services between several different needs.

There is no judgment here on the success or otherwise of its offerings, but more of an illustration of its multiple levels of operation. So far, the battery has pleased its owners (and developers), and has exceeded expectations.

This is important because the unique proposition of the battery, of course, is that it’s speed, particularly from a standing start, its modularity (it can be built up from very small units to a very large one), and its speed of construction (less than 100 days in this case).

It makes a mockery, for instance, of the Coalition’s derisory criticism that the battery is no more useful than the Big Banana in Coffs Harbour, or that it could only power the whole grid for just a matter of minutes.

What it does do is point the way to the future, and the transformation to a smarter, cleaner, faster, cheaper and more reliable grid than what we have now.

More batteries are on their way – in South Australia, the Northern Territory, Queensland and NSW – and more will follow once the market rules are adjusted to catch up with the technology.