Last month Australia slipped further down the rankings in the international corruption index. Among a wide range of factors cited by Transparency International was Australia’s “inappropriate industry lobbying in large-scale projects such as mining”, as well as “revolving doors and a culture of mateship”.

As several high-profile cases have recently revealed, the close ties that continue to exist between senior politicians, former political staffers, and the big end of town have had a real and lasting impact on the perception of political transparency in Australia.

Two examples from 2016 and 2017 clearly illustrate the extent to which such relationships can have a toxic effect on democracy.

During last year’s Queensland election campaign, the ABC revealed that Cameron Milner, former Queensland secretary of the ALP and chief of staff to federal Opposition Leader Bill Shorten, had been the main lobbyist and go-between for Indian mining giant Adani.

Earlier in the year, it was reported that former federal trade minister Andrew Robb walked straight out of his ministerial position in July 2016 to take up a lucrative position as a “high-level consultant” for Chinese-owned company Landbridge.

This was the same firm that Robb had publicly defended when it controversially acquired a 99-year lease for the Port of Darwin in 2015.

The cases of Milner and Robb not only suggest that such influence-peddling is politically bipartisan in nature, but that it can happen both during and after the relevant parties have left their positions in the public sector.

Revolving door or golden escalator?

Much has been made in recent weeks of the provisions contained in the federal parliamentary code of conduct. Among other things, the code bans former ministers from lobbying the federal government for 18 months after leaving office.

But given the fact that no current or former minister has been deemed to be non-compliant (including Robb), one could be forgiven for concluding that the code is simply a cover for business as usual.

Several prominent public figures and NGOs, including The Australia Institute and urban planner Julie Walton, have argued that the mining, energy, property and gaming industries enjoy favourable treatment in exchange for their generous political donations, or at least are perceived to.

There’s also widespread public acceptance that the resources industry was instrumental in removing Kevin Rudd from the prime ministership in 2010.

What is less well known is the extent to which big business has sought to bend the will of the body politic by directly influencing the formation of government policy.

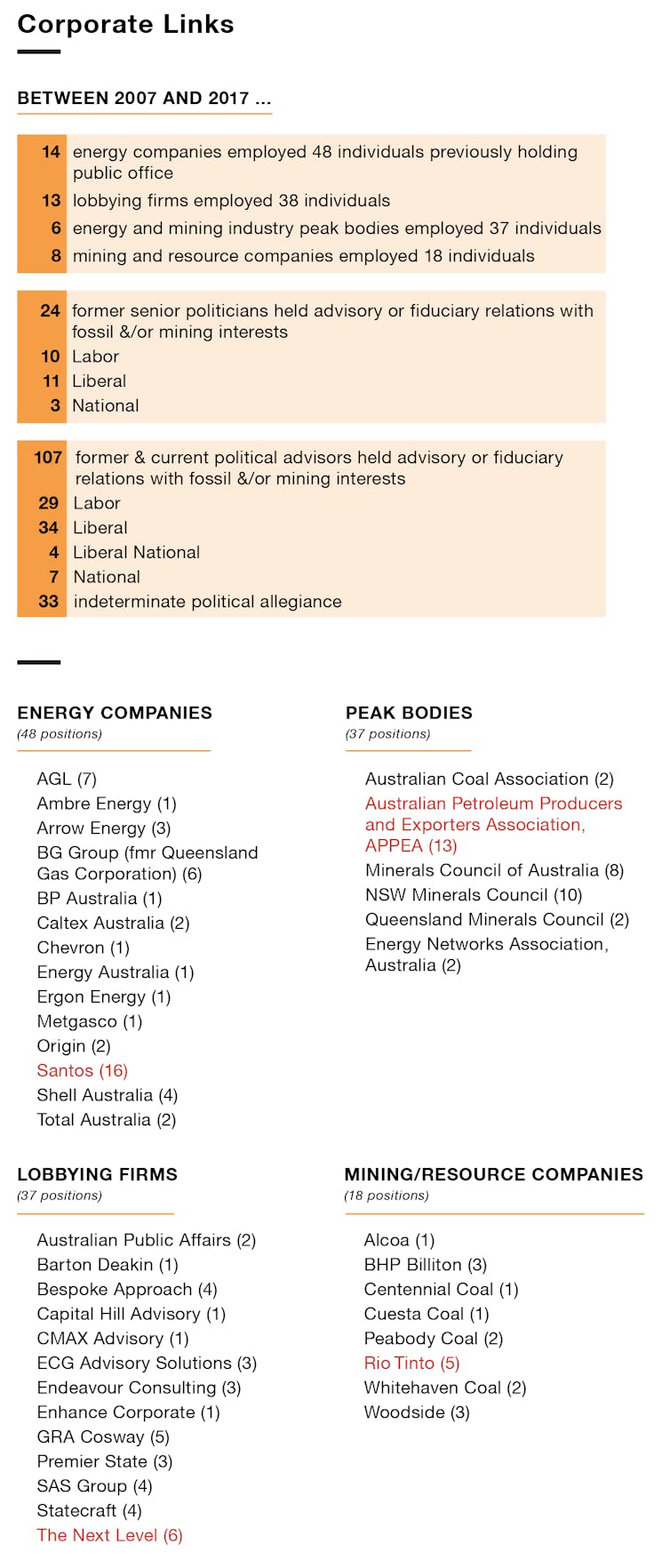

This is not just done through lobbying. All of these industries have been proactive in courting individuals who hold public office in relevant portfolios as potential allies and future employees.

Some are employed as lobbyists, some as advisors, some as consultants, and others as board members and company directors. This allows these industries to shape tax and regulatory regimes in their favour, and to drive major government and private sector investments in their own infrastructure.

The phenomenon we seek to highlight has previously been referred to as the “revolving door” between the political and corporate realms.

But although there is ample evidence for these kinds of arrangements, on closer inspection they look more like a golden escalator. The financial rewards on offer in the private sector can dwarf anything received by senior politicians and public servants while in office.

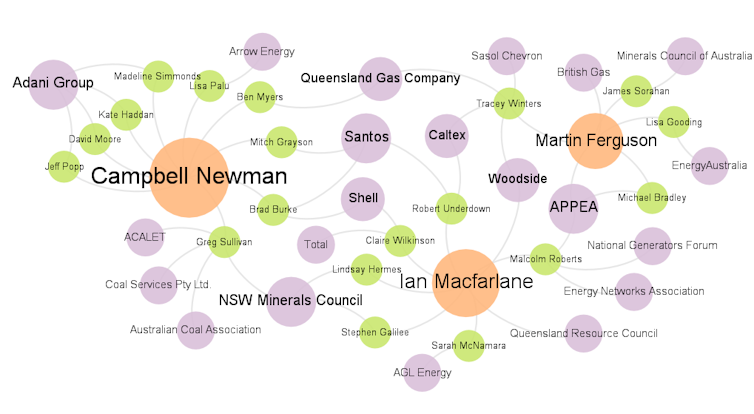

For evidence of this dynamic, we need only to look to former resource ministers Martin Ferguson and Ian Macfarlane.

Ferguson took up a position as a non-executive director of British Gas just weeks after leaving federal politics in September 2013, having already become chair of an advisory board for Australia’s oil and gas peak body, APPEA in October.

Macfarlane, meanwhile, was appointed chief executive of the Queensland Resources Council only four months after leaving federal politics.

The ‘service elevator’

There is another strategy that has also been used to great effect by the fossil fuel and mining industries in recent years. It is also used by powerful corporations in other economic sectors such as agribusiness, pharmaceuticals, gaming, and construction.

The industries in question either hire former ministerial staffers and policy analysts with relevant knowledge and expertise to advise them, or they encourage their own former staffers to take on positions as government advisers while maintaining close links with them.

When acting as staffers, these individuals are free to operate outside of public scrutiny and regulatory reach. This allows them to move seamlessly between the offices of powerful political figures and some of Australia’s largest resource companies and industry bodies.

We have compiled a database of more than 180 individuals who have moved between positions in the fossil fuel and/or mining industries and senior positions in government, or vice versa, over the past decade. This includes senior political staffers working for prime ministers and state premiers.

We have also found examples of key ministers hiring individuals straight from the fossil fuel and mining industries, who then return to those industries straight after leaving government.

This revolving door might be better dubbed a “service elevator”, ensuring that “delivery of the goods” happens away from public scrutiny.

Questions of influence

Australian governments clearly need to enact laws at the state and federal levels to prevent these kinds of activities.

We know that such legislation is not without precedent, and is therefore politically feasible. For example, in Ireland, the cooling-off period was recently set at one year, whereas in Canada it is two years and in the United States, five years.

But it is not just the rules around political lobbying that require reform. Many other areas of political activity are also in dire need of attention, including much stronger disclosure laws in relation to campaign financing and political party donations, and a significant increase in public funding for political parties, apportioned on the basis of electoral support.

Most significant, however, is the need for a federal anti-corruption body with independent investigative powers.

While there has been resistance from the major political parties to the creation of a federal anti-corruption watchdog, it would appear that the tide is turning. Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull recently countenanced such a move, as did Bill Shorten.

If our political leaders are not prepared to provide more transparency and accountability with respect to government decision-making, then we can only assume the resource extraction industries will continue to call the shots on Australia’s transport and energy policies.

Our collective failure to deal with these issues will ensure that the increasingly dire predictions about planetary boundaries being breached over the next few decades will indeed be realised.

Source: The Conversation. Reproduced with permission.