Accurate weather forecasting by the Australian Energy Market Operator could have circumvented the need for rolling blackouts in South Australia in February, an event that left tens of thousands of people without power during a searing heatwave and caused the South Australia government to seize powers to intervene in the market.

The rolling blackouts on February 8 caused a political storm and yet more accusations about the risks of too much renewable energy in a local grid. But in the first independent report on AEMO’s actions over the past summer, the Australian Energy Regulator has laid the blame squarely at the market operator.

As we reported here, this is much the same conclusion AEMO, itself, came to in its own report on the February 8 blackouts, which revealed that the network operator had relied on private weather forecasters, but had not been updating its forecasts during the day, even when it was clear that the temperatures would be above 41C.

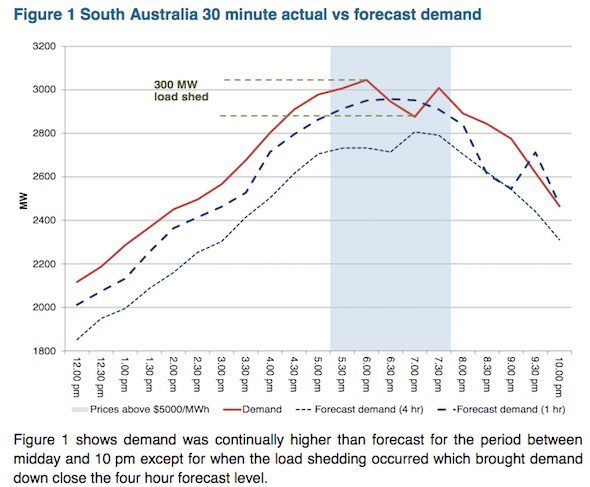

In the AER analysis the regulator notes AEMO’s forecasts, both of power demand and wind farm output, were out of whack significantly enough to have contributed to the implementation of emergency load-shedding, and to wholesale spot prices as high as $13,440/MWh.

The report notes that on February 8, the temperature in Adelaide soared to a maximum of 42°C – as had been forecast by BoM (and also by the 10-year old daughter of Green s Senator Sarah Hanson-Young) – leading to high demand for electricity in the state.

s Senator Sarah Hanson-Young) – leading to high demand for electricity in the state.

But AEMO, using lower temperature forecasts from its external service providers, “failed to adequately correct for the actual temperature observation,” the report said, leading to actual demand that was between 69MW and 312MW higher than was forecast four hours ahead.

“While events on the day [see table, right, and click on it to enlarge] are complex and some capacity was unavailable, difficulties in accurately forecasting demand contributed to the overall uncertainty of market outcomes,” the report finds.

“The lower demand forecasts and over-estimated wind generation resulted in lower price forecasts. Had the forecasts been more reflective of actual conditions, it is likely that the potential shortage of supply may have been visible to the market earlier, allowing for a wider range of potential mitigation actions to have been considered.”

One of these options would have been directing Engie to fire up the second unit at its Pelican Point power station. When AEMO finally got around to asking Pelican Point to fire up, it was too late.

The sight of one of the country’s most efficient gas generation units sitting idle while tens of thousands lost power infuriated the South Australian government, leading to its Energy Security Plan, and made others wondered what it would take for a gentailer to fire up its generation units rather than have its customers suffer blackouts.

The report is also an apparent vindication of the South Australia government, which has questioned the performance of AEMO, not just in that rolling blackout, but also in the September “system black”, and other incidents.

The only report into the system black has been conducted by AEMO itself, although it has defended its decision to take no preventative action in the lead-up to the cyclonic storms that felled major transmission lines. However, it has caused a review of its procedures.

The AER report also makes the point in the wake of the February event that it is not only renewable energy generation that can be subject to weather-related variability.

“Installed capacity isn’t always the best indication of what may be available at any particular time, particularly during summer, when high ambient temperature conditions can materially affect a generators ability to perform to its nominal installed capacity,” it says.

“It appears that AEMO did not monitor the accuracy of the forecasts such that they might have been able to make corrective action.”

AER chair, Paula Conboy, said on Thursday that – while challenging – accurate forecasting, particularly during Australia’s extreme weather conditions, was critical to the effective operation of the market.

“More accurate forecasts of both demand and wind generation may have led to earlier market signalling of a shortage”, Conboy said.

Similarly, in its review of February 9 – a 41°C day that saw state’s wholesale electricity spot prices hover between $6,755/MWh and $9,510/MWh over a two-hour period in the early evening – the AER found AEMO’s forecasts we’re again out of whack, this time in the other direction.

“On this day, AEMO’s forecasts for South Australia, four and 12 hours prior, over-estimated the state demand for electricity by around 150MW,” the report says.

“On the basis of the predicted shortfalls, AEMO encouraged generators in South Australia to voluntarily provide electricity,” the report notes.

“This request was unsuccessful, and as a result AEMO used its powers to require Engie to start and run an additional generator at its Pelican Point Power Station in South Australia, triggering the need for special pricing arrangements (“what if” pricing).

“What if” pricing affects prices in all states and ultimately led to the high prices in South Australia and New South Wales,” the report says.