The Australian government is expected to put hydrogen energy near the top of its clean energy investment shopping list, as it looks to tackle issues such as the domestic gas crisis, the increased reliance on transport fuel imports, and an opportunity to establish the country as a renewable energy export powerhouse.

Next week, the Australian Renewable Energy Agency is expected to announce that hydrogen projects will become one of its new investment priorities in the coming year, just as the country is being urged to seize an opportunity to maintain its status as a major energy exporter, but this time with “green” hydrogen fuels rather than coal or gas.

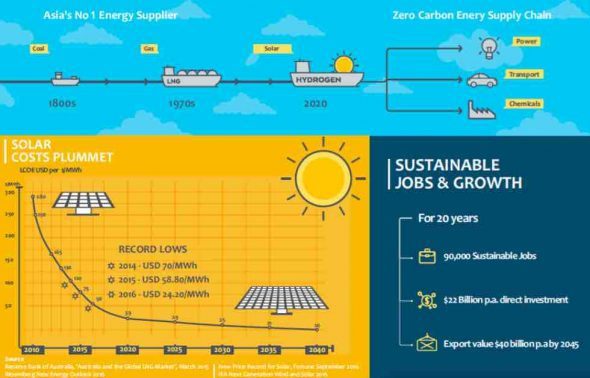

The government is being told that “green fuel” exports – powered by wind and solar – could reach $40 billion a year in the next few decades, a market equivalent in size to the export coal industry, and essential if Australia is to maintain its pivotal position as a major fuel supplier in a decarbonised world.

Hydrogen is also being pushed as an alternative to battery storage and pumped hydro to store “excess” wind and solar output in Australia, particularly in wind and solar rich South Australia, and is also seen as a potential transport alternative to electric vehicles as petrol-fueled internal combustion engines are phased out.

Victoria’s brown coal resources have been the focus of some investigations into hydrogen-based exports, particularly by the likes of Kawasaki, but this is seen as untenable in a carbon constrained world, even if they are dubbed as “carbon neutral” thanks to sequestration.

The main push now is in renewable-based hydrogen, and it is being led by South Australia and the ACT, the two states and territories with the biggest commitment to wind and solar energy.

The ACT, which expects to source the equivalent of 100 per cent of its electricity needs from wind and solar, has facilitated $180 million into hydrogen investments, including an electrolyser, a fuel cell trial and using hydrogen to store excess wind and solar.

South Australia, which is already meeting 50 per cent of its local demand through wind and solar, and could jump to more than 80 per cent within five years, has also commissioned a major study into the hydrogen economy, both for storing excess wind and solar, and as a possible export, as we reported earlier this week.

These two states are being supported by various private groups that are urging Australia to seize the opportunity to become an exporter of “green fuels” – using the nation’s huge solar and wind resources to produce hydrogen and meet huge demand for clean fuels from Japan, South Korea and other growing Asian economies.

It is also being painted as a significant military and energy security issue for Australia, given the country’s huge reliance on imported fuels, most of which comes through south-east Asia. And it is being touted as a complement to battery storage and pumped hydro to provide long-term storage to ensure there is enough energy supply for the local grid.

The push for hydrogen fuels is not new; the likes of Ross Garnaut, ARENA and the Clean Energy Finance Corporation have been pushing the idea for several years – but the plunging cost of solar and wind energy is creating what Siemens Australia head of strategy Martin Hablutzel says is a potential “tipping point” for the concept.

Siemens last month held a series of hydrogen roadshows in Sydney, Melbourne, Perth and Adelaide, attracting hundreds of energy industry participants, consultants and senior government officials to their analysis of the big three opportunities in hydrogen for Australia.

“The catalyst to this being topical is the big reduction in wind and solar costs, and the whole conversation about storage,” Hablutzel told RenewEconomy in a phone interview. “If you go back 10 years, the economics didn’t stack up. But we are now reaching a tipping point.”

Australia, he says, needs to seize the opportunity, given the huge interest in clean fuels from the likes of Japan, Korea and other economies. “We can maintain role as a major global power exporter – beyond coal and gas. But we need to start thinking about how we can continue to be a major supplier” in a carbon constrained world.

Siemens sees three big opportunities for hydrogen.

The first is within electricity grids, where using it as storage could be an answer to the excess output of wind and solar that cannot be readily used in the local grid, or exported to neighbouring states through interconnectors.

“South Australia will be the first state to encounter this,” he says. And, as if on cue, South Australia on Anzac Day reached record output of 1,540MW on Tuesday, getting close to the level where some analysts suggest that wind farms will need to be curtailed, because there is not enough capacity on the interconnector to export all the capacity surplus to the state’s needs.

“South Australia will be the first state to encounter this,” he says. And, as if on cue, South Australia on Anzac Day reached record output of 1,540MW on Tuesday, getting close to the level where some analysts suggest that wind farms will need to be curtailed, because there is not enough capacity on the interconnector to export all the capacity surplus to the state’s needs.

Hablutzel says curtailment is already happening in Germany, where some 4,722GWh of wind was curtailed in 2015, with forecasts suggesting 28,000GWh could be curtailed by 2020.

And while storage options such as batteries and pumped hydro were being considered, hydrogen could store bigger quantities and for longer periods, for weeks at a time rather than seconds, minutes, hours or days. It removes the prospect of excess wind and solar generation becoming a “stranded asset”.

The second element is using Australia’s vast resources of wind and solar – and taking advantage of their plunging production costs to supplant fossil fuels as the main means to create exportable “green fuels”, first using electrolysis to produce hydrogen (which can be used in a variety of ways), and then into chemicals such as ammonia for transport and delivery.

“Energy conversion technology (electrolysers) are still relatively early on the technology cost curve,” Hablutzel says.

“Trends suggest that production of renewably produced chemicals could be done commercially by around 2025. For some niche markets that point has been already reached today, but Australia’s objective should be to position itself as an exporter at scale.”

The big industrial giants in Japan and South Korea are already exploring such technologies, and have developed innovation and master plans to do so, and both those two countries remain among Australia’s biggest coal and gas customers.

“Renewable energy export builds on our historical role as a global energy superpower and will support the transition of our energy trading relationships beyond coal and gas into an increasingly carbon constrained global economy for decades to come,” Hablutzel says.

Another group advocating for hydrogen fuels as a significant opportunity for Australia is RenewableH2, which says Australia has huge solar and land assets that would deliver world-leading competitive advantage for solar (and wind) hydrogen production.

“Australia’s ‘stranded’ solar and wind assets have immense domestic, export and strategic value,” the company says in presentations to government and business interests earlier this year.

It says that total solar and wind hydrogen fuel exports could be worth $40 billion a year by 2045 – equivalent to the current value of coal exports.

“Japan, Korea, Europe and the US are all implementing hydrogen infrastructure and mobility (vehicle) programs. There is now major industrial, as well as policy, weight behind the hydrogen industry among our key strategic partners.”

But it also warns that Australia is as reliant on imported diesel and liquid fuels as Japan and Korea, and this reliance on imports could be an “Achilles heel” for the country’s energy security, particularly the military.

“Renewable hydrogen and ammonia production capacity is modular,” it says. “Scale-up can be progressive, located to support grid, market and defence security objectives, and aligned to demand growth.”

But, another advocate says, the potential is enormous: “We could power half of south east Asia with solar from the desert,” Geoff Walker, from the Queensland University of Technology, told a recent conference. “We have done it with LNG, why not do it with the green version?”

“The question is, how do you get to zero tailpipe emissions? There will be a portfolio of technologies, just as now there are choices between petrol, diesel, EVs and hybrids.”