The fundamental transformation of energy markets brought about by the growing incursions of renewables such as wind and solar has been underlined in a new report by the European energy analysts at Macquarie Group, who have concluded that the plunge in costs for rooftop solar PV has fallen to such an extent that its continued rapid deployment may be unstoppable.

In an analysis that broadly reflects the conclusion of UBS energy analysts about how rooftop solar PV is heralding an energy revolution, Macquarie notes that many existing fossil fuel generators in Germany are losing money and could go out of business. And even steep subsidy cuts to renewables would not reverse the trend.

“Traditional wisdom suggests that steep subsidy cuts can bring the solar build-out under control again,” the Macquarie analysts note. “We disagree, though, as the ever-increasing prices for domestic and commercial customers as well as rapid solar cost declines have brought on the advent of grid parity for German roofs. Thus, solar installations could continue at a torrid pace.”

Here are some key graphs to illustrate its point. Macquarie notes that wholesale prices in Germany have fallen 29 per cent over the last five years, while retail prices have risen 31 per cent – both movements at least partly due to the impact of renewables. But those movements pale in comparison with the dramatic fall in the cost of rooftop solar PV.

(If the graph is partly hidden in your browser, please click it to see it in full).

Macquarie says rooftop solar generation in Germany currently costs between €0.12kWh and €0.14/kWh (assuming 85 per cent debt financing and 4 per cent interest rate). These compare favourably with retail grid electricity prices of €0.28/kWh (even at just 50 per cent on-site self-consumption). But solar PV can even offer savings at industrial and commercial grid prices which are even lower at €0.11-0.17/kWh.

“Consequently, solar installations could continue at a rapid pace even without subsidies,” Macquarie notes. “Ultimately, this would threaten the role of coal-fired generation as the price setter in wholesale power price formation.”

Macquarie says that these effects seem self-reinforcing and hard to stop, unless there is a total power system overhaul. That, though, is unlikely. “We cannot see political will for such an overhaul. Quite to the contrary, German Environment Minister (Peter) Altmaier proposed in October 2012 to lift the country‟s 2020 renewable energy target to 40 per cent” (and its 2030 target to 80 per cent).

Moreover, in an election year that is likely to see the Social Democrats elected, either in coalition with the Greens or a “grand coalition” with Chancellor Merkel’s party, the pace of renewables expansion is likely to increase.

And as this story we published today tells us, support in Germany for its “energiewende” (transformation) program remains strong. (It would be interesting to see how this corresponds in Australia, because utilities here appear to be simply taking matters into their own hands, by changing tariff structures or refusing and delaying solar connections).

As we highlighted nearly a year ago now, in our story of Why generators are terrified of solar, Macquarie has its own illustrations of what is happening to the energy market. It makes mention of key milestones on May 25, when solar contributed more than 20GW of capacity into the German grid for the first time – accounting for one-third of peak demand – and on September 14, when wind and solar combined to produce more than 31.5GW (solar 16.1GW plus wind 15.4GW) in the early afternoon.

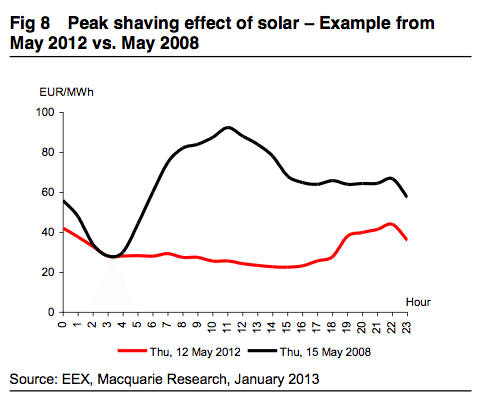

Macquarie’s examples compare typical days in May and in March – the changes to the price curve are even more dramatic than that highlighted by the Melbourne Energy Institute’s Mike Sandiford in the case of South Australia last week. The loss of the curve represents a loss in revenue.

Here is the example from May …

And here is the example for March ….

Again, the gap between the black and red lines represents lost revenue for generators.

And while the proliferation of renewables is proving to be a painful experience for utilities, it is forcing the energy industry to challenge their traditional baseload/peakload approach to energy supply. The alternative is now viewed – even by the major generator companies – as non-flexible and flexible generation, with the dispatchable energy produced by gas plants, or at a later date storage technologies, filling in the gaps between renewables. Germany is also reportedly about to announce a new tariff to encourage battery storage deployment for solar PV.

Still, the transition period promises to be problematic.

Macquarie does highlight some perverse impacts of this situation – the fact that cleaner gas-fired fuel is being priced out of the market, while lignite – what we know in Australia as brown coal – survives, and that ageing gas-fired generators are not being replaced by state-of-the-art modern plants.

However, it notes this has as much to do with the plunging carbon price in Europe, which has effectively removed the pollution price signal on dirtier fuels in the energy market, as well as the high cost of gas – most of which has to be imported from Russia. It notes that the current cost of new-build gas is nearly 50 per cent above average wholesale prices, and recently announced demand management initiatives, such as load shedding, are removing another major part of the market. That load shedding will result in up to 1,500MW of demand to be switched off in a matter of seconds, and up to 3,000MW within 15 minutes,

(Australia faces a potentially similar issue because, while it has a carbon price – at least for the moment, the main brown coal generators have been largely insulated from this by the generous compensation package, and the emergency funds provided by the government. And Australia also faces increasing gas prices).

Macquarie goes as far as to say that the German energy market is “kaput”. “Without radical overhaul, we conclude the German power system is structurally broken,” they say. The analysts note that in the normal course of events, up to 20GW of conventional capacity would be shut down, but authorities would likely prevent 10GW to retain structural integrity to the market.

Still, despite the closure of nuclear facilities, Macquarie estimates that production from thermal generators (gas and coal) would likely fall by 40TWh by the end of the decade – a reduction of 10 per cent in current output – as solar (18GW) and wind (9GW) continued their capacity additions.

German authorities are currently trying to get their head around a new design for the market, that rewards not just renewables but provides the right incentive to retain the capacity that is required to usher in that transition.

One radical proposal came from the former Head of the Federal Network Agency, who proposed to temporarily shut off, without recompense, renewable energy sources during times of excessive peak production. But Macquarie said it was difficult to imagine how this would work, as it would be difficult to decide exactly at which times the market is excessively supplied. “Moreover, it would require retroactively changing the subsidies for renewable energy plants, which would presumably not just lead to lawsuits against the German government in international courts, but also weaken general investment confidence into Germany.”