Australia’s households and small businesses will be at the centre of the dramatic energy transition occurring around us, and will play a critical role in the switch to 100 per cent renewable energy, and saving around $100 billion in costs from the business-as-usual fossil fuel scenario.

That dramatic outline is the key takeaway from the final draft of the report of the Electricity Network Transformation Roadmap that has been painstakingly put together over the last three years by the government’s premier research body, the CSIRO, and Energy Networks Australia, which represents the grid owners across the country.

The key conclusion is that Australia can and should reach 100 per cent renewable energy for its electricity by 2050, and therefor zero emissions. It can, because the technology is there to do it. It should, because of climate change and the economics.

As it concluded in its earlier report in December, this consumer led transition to a grid centred around distributed generation, solar and storage, will save a heap of money in network investment ($16 billion), and network costs to consumers ($100 billion) by 2050.

Consumers will play a critical role and lead this transition. The report suggests that by 2050, households and businesses will have installed a phenomenal 80GW of rooftop solar, accompanied by some 97GWh of battery storage.

Consumers will play a critical role and lead this transition. The report suggests that by 2050, households and businesses will have installed a phenomenal 80GW of rooftop solar, accompanied by some 97GWh of battery storage.

The 10 million households who have distributed energy resources like solar, storage, smart homes and electric vehicles by 2050 will play a critical role in how Australia manages its grid, which will no longer be based around a scenario of centralised baseload and peaking plants.

Instead,it will be based around wind, solar, storage and other flexible generation. And the key to providing that flexibility lies in the distributed nature of the grid, and taking advantage of the consumer investment in solar and storage, which will provide half of all the power needed and much of the storage.

But the stunning falls in the cost of renewable energy technologies, solar in particular, and of battery storage, means that Australia not only needs to get its transition policies and roadmaps into place, it is running out of time to do so.

The risks, the report says, is that without significant market reform and long term climate policy, the transition will be uncontrolled.

“We thought we had about 10 years to change pricing incentives,” CSIRO chief energy economist Paul Graham says. “We don’t, and if we leave it too late, we will get more customers buying distributed energy systems in places where isn’t such a need, or they are calibrated wrongly.”

That, he says, is about ensuring that consumers are reacting to signals of not just how much electricity they are using, but when they are using it. And ensuring that their assets – solar and storage – can be accessed to help manage the entire grid.

The big risk, the networks say, is that without the right pricing signals, many customers (at least 10 per cent will simply leave the grid.

The key measures, the report says, are having a stable, bipartisan, and ambitious climate policy (40 per cent reduction in 2005 emissions by 2030), cost reflective network pricing (to ensure that peak demand is addressed) and clear transition plans at state level for the local networks.

These need to be in place by 2020 or 2021. The CSIRO and ENA are hopeful that the Finkel Review will lay much of the groundwork, although it is fairly obvious to RenewEconomy that if these policies are to be delivered it is going to require a complete change in the nature of political rhetoric around energy policy and energy supply.

That means a change in the politics as well as the policy. There is not a snowflake’s chance of hell of setting the path towards a 100 per cent renewable energy grid if politicians are still saying stupid things about wind and solar.

Interestingly, the network transformation report goes into details about the 100 per cent renewable energy grid would work, and its implications for individual states.

It notes that each state grid can comfortably reach around 40 per cent penetration of variable wind and solar without much problem: from that point on, battery storage and technologies such as synchronous condensers need to be considered.

But it is only in the latter stages of the transition that new wind and solar has to be backed up like for like with storage. And that is based on assumptions that each state grid is distinct from the others.

In reality, the variability of supply will mean less back-up is needed, and the greatest need for backup will not come from those hot summer peaks, because there will be plenty of solar and storage to address that – but in the mild winters after days of cloudy weather.

But that also means that the back-up simply need not be as great, and will likely come from gas peakers that transition to biogas or a similar technology. We go into those assumptions in a separate story.

But that also means that the back-up simply need not be as great, and will likely come from gas peakers that transition to biogas or a similar technology. We go into those assumptions in a separate story.

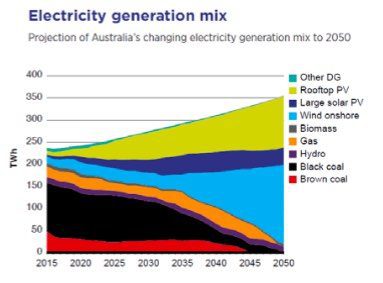

As this graph on the right suggests, brown coal will be gone by 2045 at the latest, and the remnants of black coal also gone by 2050.

Now that may come as a surprise to the likes of AGL Energy, which launched a much-vaunted rebranding campaign this week that talked of its intention to start getting out of coal by 2022 and all of it by 2050, by which point either Bayswater or Loy Yang A will be more than 60 years old. It only bought the plants in the last few years.

At this point it is worth repeating who is making this prediction of 100 per cent renewables by 2050 – not an environmental NGO, or a solar enthused university researcher. It is the government’s primary scientific research group and the owners of the networks whose responsibility it is to maintain supply.

In an ideal world, CSIRO and ENA would like greater co-ordination and for the states to move, more or less, in lockstep with each other as they transition towards 100 per cent renewables.

This graph below illustrates how the two bodies see the state-based renewables share evolving. It probably shows a conservative view, if anything, given that South Australia is already approaching 50 per cent renewable energy and the solar and wind plants already under construction will take it to her 60 per cent within the next two years.

Victoria is expected to be the next state to follow, given it is the only other state with a legislated renewable energy target. But the roadmap also suggests Western Australia will quickly adopt renewables, reading 48 per cent by 2030, even though it has not yet a formal target, but plans to pull back the massive subsidies to fossil fuel generation in the state.

The targets will require significant amounts of new renewable energy generation to be built at various points as fossil fuel plant, particularly large coal fired power stations, are retired.

“To achieve deep decarbonisation while keeping the lights on, it’s likely the eastern states will depend on the equivalent of 25 new large-scale solar or windfarms being built in just a five year window with new building activity focussing on Victoria in the 2020s, New South Wales and Queensland in the 2030s and Victoria and Queensland in the 2040s,” Graham said.

But the biggest change remains the “behind the meter” investment by households and businesses. If this is done right, the CSIRO and ENA say, it will reduce network costs by 30 per cent, cut household bills by between $400 and $600 a year, and save a total of $100 billion in spending on networks over the “centralised” or business as usual scenario.

ENA chief John Bradley notes that by 2030, the amount of solar in the current leading state, Queensland, will increase by more than 500 per cent, with more than 10,000 MWh in small-scale battery storage. By that time, the solar capacity will be greater than the current coal capacity.

This is what Audrey Zibelman of the Australian Energy Market Operator describes as the “consumer-led” transition, that will result in a grid that is cheaper, cleaner, faster and more reliable than the current one.

AEMO understands this, the networks understand this, most other energy insiders understand this too. Bradley says in the consultations held since the last version of the report was released in December has been positive.

“There has been a surprising strong level of support for the et of measures for roadmap,” he said. “The need for a clear transition plan seems to be widely endorsed.”

So, what’s the delay?