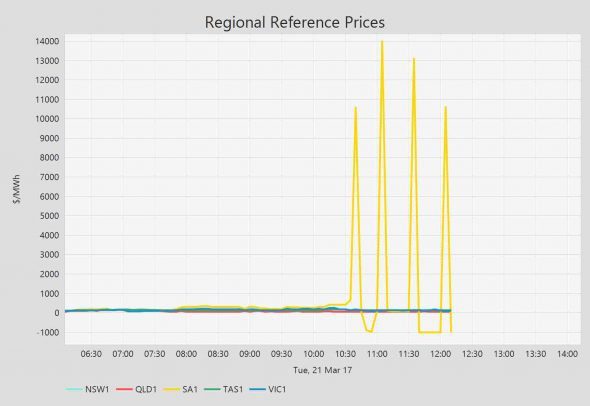

Wholesale electricity prices in South Australia soared again on Tuesday in what is being seen as another example of the small cabal of gas generators exploiting their market power to push up prices.

It comes as yet another investigation by the Australian Energy Regulator highlights how the same generators pushed the price of frequency and ancillary services to stratospheric heights in October, just as they had done a few weeks earlier.

It highlights, yet again, the fundamental problem with the Australian energy market. It has less to do with wind, solar or any technology than the market power of the incumbent generators, who have created market rules that allow them to exploit and distort pricing.

The most prominent of these is the so-called 30-minute rule, which means that prices are settled every 30 minutes, even though bidding occurs every 5 minutes. Critics, including large energy users such as Sun Metals, say this allows gaming of the prices.

Yesterday’s trading appear to be a perfect example. Note how the prices were bid up to high levels in the first or second five-minute intervals – a pattern identified by research by the Melbourne Energy Institute and others.

This guarantees a high price for the entire 30 minute period. Having created scarcity by withdrawing capacity in one five-minute interval, the market is flooded with bids as generators try to get in on the action in the subsequent five-minute intervals.

The best time to do this is when there is little competition, and that usually happens when the interconnections are constrained, often for upgrades or maintenance.

There are numerous other examples of this, such as when Origin and Snowy Hydro combined to push down prices, forcing competitors out of the NSW grid, and then used the scarcity to push up prices afterwards.

South Australia and Queensland are the most exposed, because they are at the end of the grid and their market is dominated by just two major players, and South Australia is particularly exposed when the interconnetor is down for upgrades or repairs.

When this happens, AEMO calls for enough locally sourced FCAS – frequency and ancillary services – to maintain grid security. There is actually heaps available, more than 450MW, but when AEMO calls for 35MW, that spare capacity can be mighty hard to find.

On October 18, because the interconnector was to be closed, AEMO called for 35MW of FCAS and expected it to cost no more than $100/MWh. But it ended up costing more than $5,000/MWh for more than five hours because of unexpected “problems” with two gas plants.

Engie’s Pelican Point experienced “plant problems” in the morning and had to withdraw 165MW of capacity. Wouldn’t you know it, but all that of lost capacity was the “low-priced” capacity. Tarnation!

“Difficulties in stabilising the combustion in the turbine that consequently delayed its returning to service” – the AER reported – and only 33MW of low-priced FCAS could be found anywhere in the state. So AGL’s Torrens Island filled in for the last 2MW – at a price of $11,499/MWh, which means all that capacity got that amount.

In the afternoon of the same day, it was Origin’s Quarantine gas station’s turn to have problems, with a “faulty valve” causing the plant to trip. You’re not going to believe the coincidence, but the capacity that was lost was all the lower priced FCAS. Tarnation again! And all that could be found was 29MW of lower priced FCAS in the whole of the state.

So again, Torrens Island rode to the rescue with the extra 6MW of FCAS to meet AEMO’s requirements – this time at a price of more than $12,000/MWh for low and raised FCAS – for most of the dispatch intervals from 7.05 pm to 11.30 pm.

This is not the first time that consumers have been burned. Almost exactly the same thing happened in August when the same players in the market contrived to bid FCAS prices up to similar levels. Apparently, the market operators and the regulators say, it is all within the rules.

May be those rules should be changed. In US markets, if you haven’t met your capacity commitments made a day earlier, you’d better have a bloody good reason. And the regulators go to the trouble of checking, too. Maybe that should happen here as well.