The National Electricity Market (NEM) is designed to operate at 50 Hz. Frequency deviation occurs when generation and load are mismatched. It is important in a lightly meshed and long network such as the NEM to maintain tight frequency control and that frequency response is available throughout the network.

Changes in the approach to frequency control on the synchronous units has resulted in technical and regulatory changes which have compromised the resilience of the power system to frequency variations. Consequently, an accumulation of small contingency events (as on 28 September 2016) can leave the power system exposed.

Prior to 1999 frequency deviation was addressed by mandated governor controls on the synchronous generating units. The governors operated to control frequency deviations larger than 0.1 Hz around 50Hz.

The governors provided a continuous control of frequency as they commenced acting within the normal operating band when frequency deviated by 0.05Hz from 50 Hz (rather than commencing only when the operating band was exceeded). This form of primary control, that provides fast response to frequency deviation, is mandated in other countries.

In 1999 the regulatory arrangements for the NEM were redesigned to create a real time market for the provision of all of its frequency control. The changes introduced in 2001 included:

- redefining the normal operating band from 49.9 Hz to 50.1 Hz to 49.85 Hz to 50.15 Hz

- introducing eight frequency control ancillary services (FCAS) which operate in distinct bands.

Subsequent changes in the regulatory framework discourage tight governor control by:

- attributing poor causer pays factors to synchronous generators with tight deadbands that are contributing to good frequency control

- penalising generating units which ramp in a non-linear fashion because they are providing a primary governor response to frequency deviations within the normal operating band.

Over time, as a consequence of these changes and disincentives, governor deadband have been widened from 0.1Hz to 0.3Hz or more and units can disable their governors when not economically dispatched to provide frequency control. This has resulted in a significant deterioration to the fast frequency response of the power system.

In contrast to the original efficient control action of governors, the FCAS services are inefficient because the action starts later requiring more service to control frequency and may not be located where it is required. Due to the switching between services, the control is not optimal and does not provide good primary control of frequency. For example, frequency needs to fall to below 49.85 Hz before contingency FCAS is provided to contribute to arresting the fall in frequency.

Fast primary control response to frequency deviation within a narrow deadband ensures that frequency deviations are effectively and continuously addressed. By delaying the response to a fall in frequency synchronous generating unit momentum is lost because its rotating energy is extracted into electrical energy – this is the “inertial contribution” and deceleration sets in, therefore, frequency drops lower and will require more energy to recover.

An analogy to this is a truck has to accelerate in order to maintain its speed as it goes up a hill. It must accelerate (or increase its energy input) early enough to maintain its momentum. Failure to accelerate earlier enough will result in the truck slowing down. It cannot easily regain its original speed and can only gear down and crawl up the hill or worse stall.

The resilience of the power system has been compromised by the shift to market based frequency control on the synchronous generating units. The deterioration of fast acting governor control represents a significant deviation from Good Electricity Industry Practice and fails to meet the National Electricity Objective as more services are required to be dispatched than if services were re-designed with narrow deadbands.

Current proposals for improved frequency response remain focused on market mechanisms. Implementing another market for fast frequency response will result in the same issues described above unless the market and the regulations reconsider how to incorporate good frequency control into the normal operating band. The type of frequency control required cannot be centrally dispatched – it must be in continuous operation in the control systems – central dispatch responds too slowly to be effective.

Reassessment of the approach to frequency control should be undertaken with a view to:

- reintroducing narrow mandated deadbands across the NEM

- removing regulatory disincentives to tight governor action.

Further details and supporting data are set out in the accompanying paper published 3 Feb 2017.

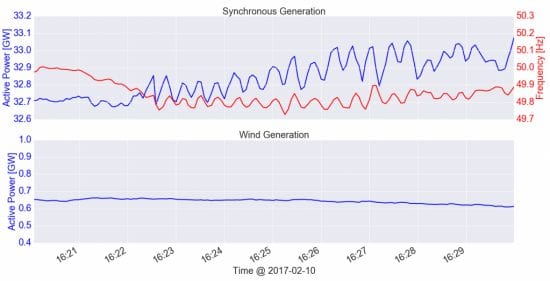

On 10th February 2017 hot weather placed the NSW region at risk, the AEMO report on the event noted that (after a number of other heat related issues occurring in the region) at 16:22 a Tallawarra unit tripped from 408MW, this reduced the frequency to below 49.85Hz and for the following 7 minutes there was a sustained frequency oscillation on power system with a 24 second period. Analysis of the 4 second data illustrates why there is an immediate primary control issue with the synchronous units on the power system.

The control (or lack of control) of the synchronous ‘baseload’ generation units are the cause of the instability of the frequency control on the power system.

Kate Summers is the Manager of Electrical Engineering at Pacific Hydro, which she has been with for over 12 years.She specialises in technical regulation issues with renewable energy in the NEM and power system engineering.