When the ALP lost government in 2013 Australia had a secure, but rising, cost of electricity. Network prices had risen substantially, causing bill shock mainly because the AEMC and COAG had failed to rein in the Australian Competition Tribunal; and because networks were – and are – entitled to earn a perpetual rate of return on sunk costs, even when those costs have been fully recovered and notwithstanding that capacity utilisation has fallen.

The carbon tax was adding around $30/MWh to electricity prices, but the increase in network costs and the community emphasis on energy efficiency driving lower consumption were the key factors. The wires and poles cost tripled between 2008 and 2013.

However, over the next five years it’s the generation cost that drives prices up from $274/MWh (before retail discounts) to maybe $324/MWh (and the federal government loses, say, $10 billion of tax revenue in the process).

More importantly Australia had a suite of policies that:

- Encouraged energy efficiency. Every large corporate had to explicitly report on its energy efficiency plans.

- A carbon tax. Although this was meant to transition to floating carbon price it was actually far more effective as a tax. The advantages were.

- It raised final prices encouraging efficiency.

- Simple to administer

- At $30/t raising more than A$10 bn a year. By contrast fuel excise which most people don’t really think about raises about $12 bn a year. For an average house in Australia that carbon tax added $180 per year to their costs. By contrast the fuel excise at $0.38 litre and assuming a motorist uses 9 litres/100 Km, and drives 15,000 km a year costs say $600 a person. In two car households the cost could easily be over $1000 a year. This to your author’s mind shows the difference between perception and reality.

- The known price enabled both generators and consumers to plan around the fixed cost. Space does not permit in this article but providing confidence around the cost of capital is the main way Govts can contribute to keeping electricity prices low.

- Most importantly it penalized high carbon emission raising the variable cost of brown to or above that of black coal and making gas cheaper, at the time, than coal

But what if the carbon tax forced old generation to close but no new generation was built? Wouldn’t that be a problem for energy security? So that’s where…

- Renewable energy incentives come in. That was done by the LRET. In addition, state governments decided to offer high feed-in tariffs for rooftop PV. This lead to a glut of RECs and so the LRET scheme was split in two, small and large. The surplus of large certificates has only recently been worked off. We’ve criticised the LRET policy several times as being a high cost and unreliable way to get new renewables into the system but it did at least a provide a carrot. Reverse auctions can do the same job in a cheaper and more targeted fashion.

The net impact of these policies was to raise final electricity prices to households by 10 per cent and to business by about 15 per cent. By and large the Australian system was regarded as one of the best in the world. Fig 1 shows that the explicit cost of the LRET and SREC scheme is small, even at today’s inflated REC prices.

The coalition eliminated the old policies, but didn’t replace them with anything new

Energy efficiency was completely de-emphasised.

The carbon tax was abolished. This worked in the short term to lower final prices but also made coal-fired electricity much more competitive against gas, and this partly explains why gas generators sold off their gas.

Because demand was low (consumption had fallen by a cumulative 9 per cent) there were no peak price events and so gas peakers sat idle.

The Federal government also attempted to eliminate the RET, but in the end was able to do no more than reduce it. The main reason why the scheme wasn’t eliminated was because all the consultants said – surprise, surprise – that the new supply the scheme engendered helped to keep prices down. Technically there was a transfer of wealth from thermal owners to renewable owners.

Because renewable energy investment is all about confidence (specifically 40 per cent of total costs are the cost of capital) and the federal government had made it very clear it was anti-wind and anti-renewable energy, it took a long while for investment to get restarted.

Low prices worked as well as high prices at causing adjustments

Coal and gas fired generators weren’t making much money, so their owners responded by merging and closing the least profitable generators. By far the worst and most disgraceful example of this was in Queensland, where the state government merged three generating companies into two and sat by while those two companies rorted their competitive advantage in the state.

But we also had the closure of Wallerawang which was 5 per cent of the NSW market, and AGL buying Macgen. The cumulative impact was shown when Hazelwood closed. Holding an ACCC inquiry today when the government had chances to intervene in the AGL/Macgen takeover is a clear case of shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted. And, it needs to be said, typical of policy in this area.

Announcements as a substitute for policy

To this day there is no federal policy other than what’s left of the RET. Zero, zip, nada. There is no policy because the federal government is opposed to the policies being adopted all over the world, which a majority of Australians want and which the electricity industry wants.

This is leading to a breakdown of the cooperative federalism of the past decade and is another impediment to reform of the management of NEM. In fact, there is no management, just a committee (COAG energy committee) and government organisations with no KPIs (the AEMC for instance). There are announcements “Snowy 2”; and now, an after-the-horse-has-bolted ACCC review of retail prices.

I mean this is genuinely humorous. Everyone in the industry knows why prices are going up. It’s not greedy retailers. I mean retailers are greedy, but it doesn’t do them any good. Most small retailers struggle. Origin Energy, AGL and EnergyAustralia have had a terrible return on funds employed until very recently.

Prices have gone up, firstly because of constant returns to monopoly regulators on an ever increasing regulated asset base, but lower volumes and secondly because federal government policy has eliminated confidence in new investment, leading to a shortage of supply relative to demand. There is also a cost to consumers from the RET scheme, but that’s double what it should be due to federal government killing off investment.

SNAFU but still a great future awaits

So what have we got?

- An ageing thermal fleet.

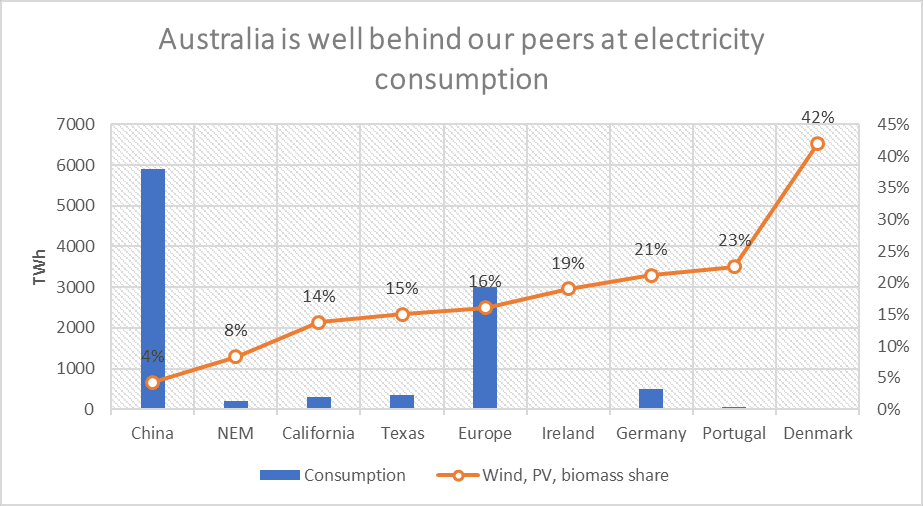

- A globally low share of wind and PV. Across the NEM wind and PV were 9 per cent of output in 2016 compared to 18 per cent in Europe, 14 per cent in California and 15 per cent in gas and oil rich Texas.

- Prices which are now high by global standards

- A thermal supply oligopoly

- No gas to run the existing gas generators let alone new ones

- An electricity system where security is dependent on fewer and fewer thermal generators.

Some might see this as a hopeless situation, but because of Australia’s fantastic wind and PV resource, and because the cost of wind and PV has fallen, its actually a great opportunity to build a 21st century grid that will be the envy of the world.

Wind in the USA produces electricity at US $42/MWh = A$63/MWh unsubsidised (the consumer pays $20/MWh and the tax credit is worth about $22/MWh). Capacity factors in the USA are getting up to 45-50 per cent – by comparison, a typical combined cycle gas plant is at 50-60 per cent. Australia’s newest wind farm is at 43 per cent in its first three months.

Australia’s 5GW of distributed solar and the low energy density of networks (electricity consumed per Km of wires) makes this a fantastic country to build a decentralised grid using solar PV and household storage. But again, where is the federal government vision? Where is the policy? Where is the modelling? The lack of initiative and policy cannot be excused on any level, 3 year election cycle or no. Australians have a right to, and do expect more.

Despite our advantages we are well behind what the rest of the world is up to.

In the USA a very recent survey of 600 utility companies confirmed they they plan to continue their decade old shift to wind, and PV and distributed energy despite the election of Donald Trump. And why wouldn’t they? Its good economics and sound policy with a decade of experience behind it.

The federal government has criticised state policies but offers nothing in return

The Victorian and the Queensland governments have all gone through a process in putting together their policy. In Queensland, the government commissioned a report, lead by an ex-Macquarie Banker (“The Mugglestone Report”) that found there would be no impact on prices from a 50 per cent renewable target. That report might be right or wrong, but where is the federal government’s expert report that contradicts it? Guess what? There isn’t one.

In Victoria there has been a long process with workshops and industry consultation. Everyone has a say and the process is modelled on the demonstrably successful ACT process.

Contrast that with the Snowy 2.0 announcement (just announced out of the blue one morning, well in advance of the final Finkel Report), or the federal government’s attempts to get a new coal-fired station built in North Queensland. Make no mistake, it’s the coal industry that wants that power plant. CS Energy, one of the Queensland generators, Origin Energy, AGL and Energy Australia, the four largest generators in Australia have made it clear that the project can’t be justified without an explicit subsidy and is contrary to their policy direction.

How can this be the way to do policy development in Australia? Is it any wonder that people lose faith in government when it proceeds in such an obviously irrational fashion? Any large company listed on the ASX would be in deep trouble with its shareholders if it proceeded in the same way.

David Leitch is principal of ITK. He was formerly a Utility Analyst for leading investment banks over the past 30 years. The views expressed are his own. Please note our new section, Energy Markets, which will include analysis from Leitch on the energy markets and broader energy issues. And also note our live generation widget, and the APVI solar contribution.