Alinta Energy chief Jeff Dimery has warned that the owners of Australia’s remaining coal-fired power plants – particularly those in the Latrobe Valley – have “grossly understated” the cost of closing their ageing fossil fuel assets, and will be a cost that will be born by communities, consumers and governments if not managed properly.

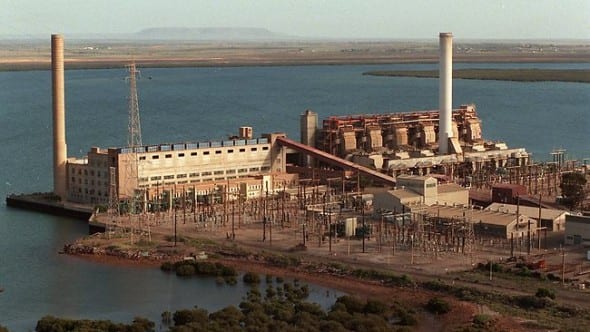

Alinta, which closed its Northern and Playford coal-fired power plants in South Australia in May, says “had zero government support or assistance” in making the decision to close the plant, Dimery said, a decision it made on the basis of economics.

But he said the cost of the closure of the South Australian Flinders Operations, including the associated coal mine – “a relatively small operation compared to other coal-fired stations on the NEM” – had cost the company $200 million; vastly more than what other generators were estimating for the withdrawal of their assets.

“This is interesting, when you look at the Latrobe Valley,” Dimery told the Disruption and the Energy Industry Conference co-hosted by RenewEconomy in Sydney on Wednesday, pointing in particular to the estimated costs of closing Engie’s Hazelwood and AGL Energy’s Loy Yang, both in Victoria.

“Our view is they’re still grossly, grossly understated ….. Have you guys seen the size of the hole in the valley?” He added later: “They are kidding themselves if they think that their provisions are in any way adequate.”

Dimery said the cost of closing coal plant and mines was divided fairly evenly between the cost of rehabilitation and restoration, the cost associated with the workforce, and the cost of “changing out your market position.”

According to a 2015-16 parliamentary report, the cost of closing the Hazelwood coal mine, alone, was conservatively estimated at $332 million. But the companies that own such plants have allocated only a fraction of those costs.

“It’s quite a big dilemma for companies,” Dimery said. “It’s not a straight forward thing to do… the unscrambling of the egg, getting your hedges, recuperating those in the market place.”

Interestingly, Dimery admitted that Alinta should have closed Northern much earlier than it did, and should have done so soon after the private equity group that owns the company bought Alinta.

“We got it wrong. It was a bad investment,” he said. But any company that did invest in coal generators knew the risks involved and he was not an advocate for contracts for closure, or payments to companies like AGL and Engie to close their plants.

“We shouldn’t reward people who make investments in yesterday’s infrastructure,” he said.

“I don’t have a lot of empathy or sympathy for governments paying coal-fired generators to close. Especially because they will catch those benefits of last man standing.

“In the case of Victoria, if Hazelwood was to close, there would be quite a big benefit to Loy Yang, so how much of that would flow back to the customers?”

As we have noted on RenewEconomy on various occasions before, the issue of closure of coal fired generators is complex.

AGL has argued in the past that governments should encourage early closures by helping fund costs – and did not respond well to a proposition by ANU researchers suggesting other coal generators should contribute to fund the closures.

But at a Melbourne conference in June, AGL chief Andy Vesey said he was “not a fan” of government paying for plant closure and that his company had been advocating for the orderly exit of plant in Australia, “because the alternative is ugly.”

“When we think about orderly transitions, we do need to be clever… There was always this question of paying for closure; I’m not a fan of paying for closure,” he said.

“I’m a fan of investors dealing with the consequence of their investments, good or bad.

“What we need is a holistic approach… (such as) a broad industry-wide securitisation program.

“This was done many times in many markets,” he said, noting the example of the deregulation of the US nuclear market.

“And it can be done here. It’s a manageable problem. But what we are saying here is that the move needs to be towards an orderly transition, because the cost of a disorderly transition is significant.

And to an extent, Dimery agrees: “Our closure didn’t come as any surprise to the authorities. We had been in communication with all the relevant authorities for a few years before we closed. Let’s say there was a very mediocre response.

“We know coal-fired power stations are going to close. Regulators and governments need to be planning for that now, not waiting and then responding,” Dimery said.

“What’s next? Hazelwood? It would be interesting to ask the state government what planning they’re doing for that.”

So how do we avoid what happened in South Australia since the exit of coal in the market?

“I definitely think something like a cap-and-trade scheme, the carrot and stick,” said Dimery.

“Over time the supernormal profits (generators) would earn as last man standing could be distributed more evenly.

“This is a more even-handed transition opportunity in the longer-term; the whole market design needs to be looked at.”

On renewables, Dimery said Alinta had plans to roll out 600MW of “incremental renewables” on Australia’s east coast, and argues that the mandate for renewables growth should be based on a federal policy, and not state-based schemes.

He also rebuffed the idea that a lack of incentives for the closure of coal plants had had the effect of stalling renewables growth.

“We didn’t makes space for (renewables) in SA with our Flinders assets, but they made their own space. And that will happen in other states,” Dimery said.

“I would argue the reason we’re not seeing new renewables in NSW and Victoria is that the big coal-fired generators (in those states) are also the big retailers.”