Rooftop solar and battery storage will account for more than half of Australia’s electricity needs by 2040, reducing the need for fossil fuel generation, as the share of fossil fuels falls by more than half to around 40 per cent.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance says Australia’s power sector will fundamentally change over the next two decades, as households and businesses turn to rooftop solar and storage and utilities shift to renewables to replace ageing coal and gas plants.

It is part of a massive global shift, with more than $3 trillion being invested in small-scale solar and battery storage worldwide, as the global energy system becomes largely decentralised.

The report predicts more than 50 per cent of Australia’s generating capacity will be located “behind the meter” by 2040, meaning that consumers will become “pro-sumers”, generating and consuming their own electricity. BNEF predicts 37GW of small-scale solar PV – mostly on rooftops – and 33GW of battery storage will be installed by then.

“This will be driven by the superior economics of these technologies, which will be able to supply consumers with electricity at a lower cost than the grid” said Kobad Bhavnagri, the Australian head of Bloomberg New Energy Finance and co-author of the Australian chapter of the report.

The BNEF report follows predictions from the Australian Energy Market Operator, and even some of the main utilities, which follow along the same lines. Last week, AEMO forecasts suggested that rooftop solar capacity would overtake coal capacity by 2030 and that, within 10 years, rooftop solar would be providing 100 per cent of grid demand at certain times in South Australia.

The BNEF predictions for Australia are part of a global trend that will see energy systems move from centralised to decentralised grids, including in developing nations.

Some $2.2 trillion is expected to be spent globally on small-scale solar, as capacity grows 17-fold to 1.8TW (that’s 1.8 million megawatts). But nearly half of this ($US1 trillion) will be in developing economies, in many cases bringing electricity to remote villages for the first time.

Indeed, solar and wind energy will dominate global installations out to 2040, with $US3.7 trillion spent on solar (mixed between large and small-scale) as the cost of solar technology halves again. The forecasts above are based on no further subsidies after 2018, be that feed-in tariffs or net energy metering – from 2018, except for offshore wind, which will see subsidies end from 2030.

Part of the problem is that the high cost of gas means that gas-fired power stations will likely close before coal plants, meaning that the great “gas transition” will not occur. This is one reason why Big Oil recently called for a substantial global carbon price to help push out coal generation. The one exception might be the US, where gas is cheaper and the government has strict emission limits on coal generators.

In Australia, the grid faces similar problems. Just over 29GW of fossil-fuel plants will be retired by 2040, including some 12GW of coal capacity, but 8GW is refurbished to prolong its operational life.

“Old coal is very cheap”, Bhavnagri said. “With our existing suite of policies, coal generators will run for as long as is physically possible.”

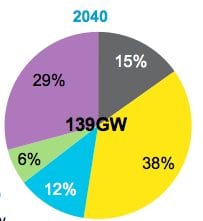

But Bhavnagri said any new large-scale capacity in Australia would be almost exclusively renewable. He predicts large-scale solar PV (currently little more than 130MW) will reach 15,000MW, overtaking wind energy (now 3,500MW) which will be 13,000MW.

BNEF says these future large-scale solar projects will be lower in cost than building new coal or gas generators, even without subsidies.

“The economics of new plants are very different from old”, Bhavnagri said. “Old coal is cheap, because only the running costs need to be met. But building new coal or gas is very expensive, as construction is capital intensive.”

Coupled with the relentless growth in rooftop PV, this will mean over half of Australia’s power capacity, and 59 per cent of generation, will be renewable by 2040. The grid will be kept stable by large amounts of flexible capacity, which includes at least 33GW of battery storage – also more than Australia’s current coal-fired fleet.

“This will require sophisticated market mechanisms to be developed to enable the system to effectively utilise these assets”, Hugh Bromley, BNEF’s specialist in distributed energy, said.

“Energy storage will need to be used to meet peak demand in winter from 2033, and households will have more than enough battery capacity to do this. But the grid will need to be managed in a much smarter way to co-ordinate the millions of new household participants.”

Despite the change in makeup, Australia’s power sector will not decarbonise substantially until 2036. The low cost and long life of coal generation will mean power sector emissions fall by only 9 per cent by 2030, compared to 2014.

“It is not until 2040, when the bulk of fossil-fuel retirements have taken place, that power sector emissions substantially fall,” Bhavnagri said.

“Carbon emissions will remain stubbornly high unless coal closure is accelerated. Additional policy will be required if Australia is to set a goal for emissions reductions at the Paris Summit that is in line with our major trading partners.”