The French company that owns the Hazelwood brown coal generator in Victoria – the dirtiest power station in Australia – has issued a “call to arms against coal.”

Gerard Mestrallet, the chairman CEO of GDF Suez, which now calls itself Engie as part of a major corporate make-over, signalled a big push against coal-fired generation in a series of meetings earlier this month at a major gas conference and a pre-Paris business seminar.

The comments were made as Europe’s major gas companies – of which Engie is one – called for a switch from coal to gas, and for a significant carbon price to be imposed to hasten that transition.

Engie – which owns plants ranging from coal, gas and nuclear, to increasing investments in wind, solar and hydro – is also forecasting the decline of centralised fossil fuel generation.

It argues that 50 per cent of all generation will be sourced locally, rather than from centralised coal or nuclear generators. It is forecasting a massive energy transition as generation becomes decentralised and digitised.

“Technical progress is powering an energy transition that is not just European, but global,” chief operating officer Isabelle Kocher told the World Gas Conference in Paris earlier this month.

“As energy solutions become smaller and smaller, so energy itself is becoming increasingly local: looking to the future, more than 50 per cent of energy generation will rely on local sources. The sun is local, and so is the wind.”

That view conforms with the outlook of other major European and US utilities. Australian utilities are also seeing the transition taking place, although they differ on just how profound it will be.

Engie has also pulled out of bidding to build a new 1,000MW coal-fired power plant in South Africa. A report in finance journal IJGlobal said no official reason had been given for the withdrawal, but quoted a source that said Engie was “purely exiting due to new concerns over supporting new coal generation.”

Engie recently opened a new wind farm in South Africa and is leading a consortium that is building the Kathu solar park, also in South Africa – a 100MW concentrated solar plant along with a storage system.

The company has declined to comment on the South Africa coal decision, but recently Mestrallet said this about quitting the coal industry in Europe: “The choice we have made is very clear. We have stopped investing …. in thermal power generation in Europe and we are investing in renewables.”

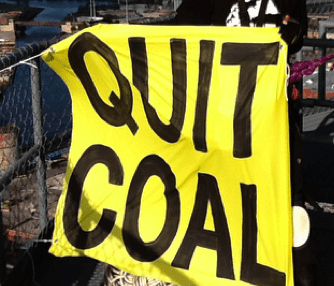

At the WGC, Mestrallet and Total CEO Patrick Pouyanne issued what the official program described as a “call to arms against coal”, pushing for gas to be adopted and helped by an international carbon price.

But what does this mean for Australia, where Engie owns the 1.5GW Hazelwood power station and the 1GW Loy Yang B coal generator, along with other assets such as the Pelican Point gas generator in South Australia? Can Engie say one thing on the international stage, and do another in its portfolio?

The 44-year-old Hazelwood power station is the dirtiest coal generator in Australia and the third-dirtiest in the world, with a carbon intensity of 1.4 tonnes/MWh. The new Victorian Labor state government is coming under pressure to push for the closure of the generator, given its health impacts, the fire last year and the damming follow-up report, as well as the huge amount of excess capacity in the network.

Currently is has a licence to keep operating until 2026, although an analysis by two Harvard fellows estimated the cost of the plant’s emissions at $900 million a year.

Given Engie’s new rhetoric about climate change in the lead-up to Paris; its ownership by a government desperate to seal a climate deal, its own push to dump coal, its push to to impose a carbon price, the falling profits of the generator, the controversy and costs of the mine fire and its impact on local communities, and the company’s recognition that the world is changing rapidly to decentralised generation, it is hard to imagine how they could justify any moves that call for the long-awaited closure.

As Mestrallet himself noted when speaking to analysts earlier this year, there is no doubt about the pace of the “energy transition” across the world.

“It is really a global trend. It is an irreversible movement pushed by the technology, at the same time through the digital revolution and also the renewable revolutions in technologies for wind, for solar, for heat and miniaturisation of the equipments.”

Mark Wakeham, from Environment Victoria, said pressure will increase on Engie in the upcoming inquiry into the Hazelwood fire, which has already cost them hundred of millions of dollars in lost income and repairs, and the potential liability that the company faces in future.

“You would think it will concentrate some minds in Paris,” he said. “That highlights the need for a Victorian government plan for the future of the region,” he said, noting the abrupt closures of smaller power stations in Anglesea in Victoria and Port Augusta in South Australia.