The Australian government and big oil companies like ExxonMobil found they had a lot in common this past week. Both went to the Lima climate talks convinced that the demand for their fossil fuels will never waiver. Both will leave with their confidence challenged.

The Lima climate talks ended – at about 3am on Sunday after running more than a day overtime – pretty much as expected: laying the groundwork for a new climate deal to be sealed in Paris, even if it didn’t remove any of the major road-humps.

Those road-humps will be gradually eliminated and managed in what will seem like an endless succession of mini-summits, bilateral meetings, and organized climate talks through 2015, ensuring that climate remains at the forefront of the political and economic agenda.

It is true that no one really expects Paris to be the big bang event that solves climate change. It will not have binding targets on all countries, and even UNFCCC executive secretary Christiana Figueres admits it will unlikely secure sufficient commitments to effectively cap global warming to less than 2C.

Those “top up” commitments will have to come in subsequent years. But what Paris will provide is a clear investment signal to move to clean energy and a decarbonised economy, and a clear signal that continued investment in fossil fuels is a high risk game.

Not much of any consequence got cut out in the Lima negotiations, and one of the key planks of a Paris agreement remains in place – the complete phasing out of fossil fuels by 2050. And – much to the horror of foreign minister Julie Bishop – it had the explicit support of more than 100 countries.

That fact that fossil fuels is now an incredibly high risk industry has already been made clear by the financial markets. The world’s stock exchanges have been struggling in recent weeks in the face of a plunge in oil prices to five-year lows.

Much of the world’s fossil fuel reserves – oil and coal – cannot now be economically extracted and delivered to customers at current market prices. Much of the analysis has focused on the short term causes of that – a refusal to turn off supply from the Saudis (who can still make a profit at such prices).

But not much is being said about the longer term impacts. The fossil fuel industry has for decades relied on uninterrupted capital flows. But those capital flows are now being re-assessed – both because the risk/reward investment in new resources is becoming unacceptable, and because competing technologies – wind and solar – are now cheaper and better bets in many parts of the world.

This is the great dilemma for the Abbott government. As global investment bank HSBC pointed out last week, exports are equivalent to 20 per cent of Australia’s economy and energy exports were 28 per cent of Australia’s total exports in 2012-13. We are now seeing the impact of a big fall in iron ore prices on Australia’s balance of payments, and its budget.

HSBC economist Zoe Knight wrote that Australia tried showcase its climate credentials at Lima (hijacking $200m in climate funds from the foreign aid budget and talking up Direct Action), but its efforts belied the fact that the Australian economy would still be vulnerable to policies set in the rest of the world – a “carbon isolation” made more acute by its repeal of the carbon price.

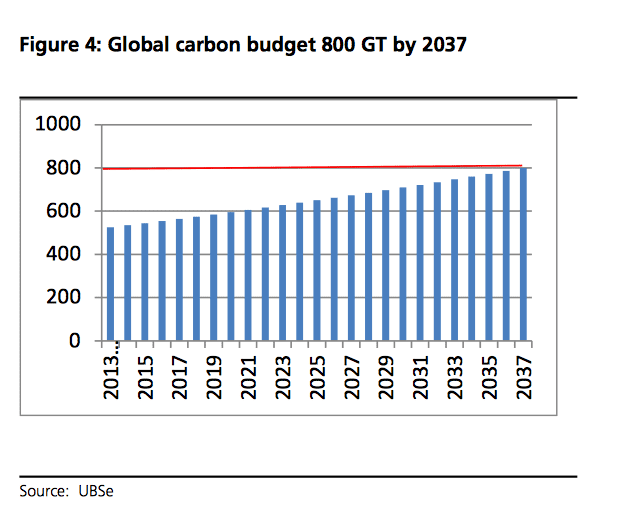

Another leading investment bank, UBS, used its analysis of the Lima talks to repeat the “carbon budget” (see graph) that underlines the point that financial analysts also see the decarbonisation of global and individual economies as a major factor in deciding where capital will flow.

Another leading investment bank, UBS, used its analysis of the Lima talks to repeat the “carbon budget” (see graph) that underlines the point that financial analysts also see the decarbonisation of global and individual economies as a major factor in deciding where capital will flow.

Erwin Jackson, the deputy CEO of The Climate Institute, said Australia will be under intense pressure to deliver a meaningful reduction target next year – as even countries such as Ethiopia and Mexico, as well China and India, make their commitments (for the first time from developing nations –this is a major development of Lima).

“All countries have to justify how they think it will fit in with the 2C target,” Jackson told ABC Radio National. “Countries cannot backslide.”

Australia is already facing difficulty because new analysis shows that – thanks to some creative accounting procedures – it will in fact be lifting industrial and energy emissions by between 26 per cent and 50 per cent by 2020 (from 1990).

Now, without any more sleight of hand on land use available to it, Australia must reverse that growth, and quickly. Backsliding, though, is exactly what Australia has locked itself into. It has dumped the carbon price – already provoking an increase in emissions – is trying to slash the renewable energy target, and has sought the abolition of a range of instiution.

“We’re heading on a trajectory where the world does not us traditional fossil fuels any more,” Jackson said. He said Australia needs to take broader view of its interests, beyond those of the Tony Abbott task force – like its review of the renewable energy target – is looking only to protect a narrow set of industries.

“The posture of the government at the moment appears to seek to minimise the imagined threats to major polluting businesses. This is blocking it from seeking economic opportunities in renewable energy and climate solutions that could maximise its influence in climate negotiations as we head to Paris next year.

“Lima has taken a broader view. This is an opportunity for the government to lift its head about short term sectoral interests … how do we prosper in a world moving towards climate change.” Rather than closing down access to carbon markets, and “knee capping” schemes lik the RET, it needs to be doing the opposite.

Jennifer Morgan, the global director of the Climate Program, at the influential Washington-based World Resources Institute, said the “most inspiring development” in Lima was an outpouring of support for a long-term effort to reduce emissions.

“Over a hundred countries now advocate for a long-term mitigation goal. This would send a strong signal that the low-carbon economy is inevitable,” she said.

A few politicians have seized on what this means.

Said former Mexico president Felipe Calderon, now chair of the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate: “This week in Lima we have made progress towards an international agreement that will send a clear signal to businesses and investors. There is still considerable work to be done. But I am encouraged that countries, all around the world are beginning to see that it is in their economic interest to take action now.”

And, of course, Australian Greens leader Christine Milne: “Phasing out fossil fuels will be the global conversation in 2015 whether Tony Abbott and Julie Bishop like it or not,” she said in a statement.

“Less than 2 degrees’ is not one of Prime Minister Abbott’s slogans. Nor is a commitment to a long term goal of decarbonising the planet by 2050. But that is what the world will be negotiating in 2015.

“Julie Bishop let the cat out of the bag when she said, “How could one possibly commit to having fossil fuel free world by 2050?” Readily Minister, if we care about the climate.

“Australia needs to phase out fossil fuels and move to 100% renewable energy for the climate and for our economy. The writing is on the wall for big coal, for the Galilee and Bowen basins and coal ports and railways. They will be stranded assets.”

The difference now is that this cannot be readily dismissed as a left-wing, enviro-fantasy. It is now part of not just mainstream political thinking (beyond the shores of Australia), but also mainstream financial analysis. And that’s what will count in the end.

But that is yet to sheet home to the Abbott government, with the possible exception of Bishop. Alhough this is not yet clear. Said Oxfam: “Australia attended the talks and that’s about the best thing you can say about their role in the process.”