Out with the old, in with the new. That’s the dramatic new strategy of E.ON, Europe’s largest utility, which on Monday announced it was dumping conventional energy generation and would focus instead on renewables, distributed generation, and customer solutions.

The stunning divestment – coinciding with the first day of the annual climate change talks in Lima, Peru – is the most dramatic in a series of announcements by major utilities in the EU and the US in recent months, flagging a move towards wind and solar, decentralised generation, and a move away from the centralised model and conventional generation that has dominated the energy market for more than a century.

E.ON says it will focus exclusively on renewable energy, energy efficiency, digitising the distribution network and enabling customer-sited energy sources like storage paired with solar. Its main markets will be Europe and North America, and CEO Johannes Teyssen said the split was necessary because the new energy system required a compete change of culture, and it was impossible to grow two businesses in the same organisation.

“We’re already experiencing how difficult it is to combine these two very different cultures in a single organisation,” Teyssen told a news conference on Monday. “And we have to assume that the new energy world will become even more dynamic and diverse than we can imagine today,” he said.

Effectively, what E.ON is doing is a new take on divestment, occurring within the biggest companies. E.ON is divesting its fossil fuel interests before investors divest themselves of it. It follows a move by RWE to focus on distributed energy, while Vattenfall, another major utility, is looking to divest its brown coal generation business in Germany just as the German government contemplates exiting coal in the same way that it put a deadline on nuclear.

It also follows the announcement by NRG, the largest private generator in the US, with a portfolio the equivalent size of Australia’s entire grid, which announced last month that it would cut its carbon emissions by 50 per cent by 2030 and 90 per cent by 2050. It said this would establish a “clear course towards a clean energy future.”

The E.ON announcement is significant because it, along with the other major utilities, has been one of the strongest opponents of the “energiewende” (energy transition) in Germany. Ultimately though, in the face of strong government policies, it has accepted the inevitable.

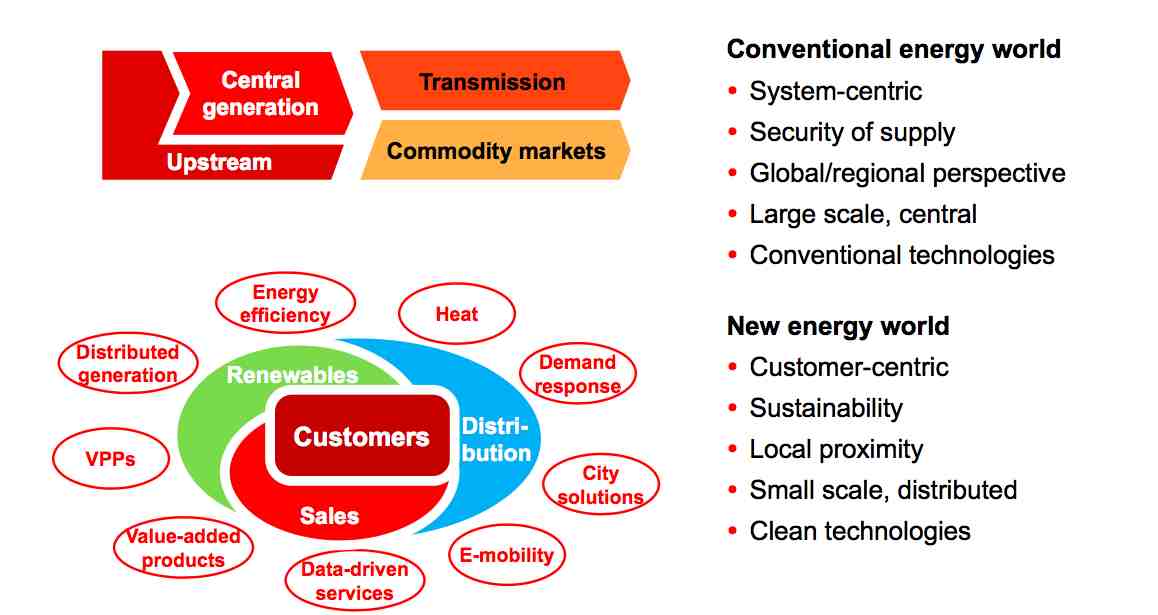

This is how E.ON sees the future of energy generation. There is the conventional energy world, based around large scale, centralised generation (coal, gas, nuclear), and the new energy world, focused on the customer, on sustainability, on distributed energy models (local generation and storage), and renewable energy.

What they are doing is splitting into listed companies. The new E.ON will consist of renewables, networks and customers, while the “old utility” will own all thermal and hydro plants and the global commodities business, and the remaining nuclear assets. E.ON shareholders will receive a majority stake in the “old utility”, but E.ON itself intends to sell its stake in the old utility.

Like any company or bank with dud assets – they are splitting their business into two, good and bad, old and new.

As UBS analysts noted: “This is the most radical transformation E.ON could have chosen, but we think it makes strategic sense and could create more value and growth than the traditional integrated business model.” It noted that E.ON clearly thought there would be no renaissance of conventional generation, and recognised that “green utilities” would get a higher rating by investors.

This is how Teyssen explained the new system:

“Until not too long ago, the structure of the energy business was relatively straightforward and linear. The value chain extended from the drill hole, gas field, and power station to transmission lines, the wholesale market, and end customers. The entire business was understood and managed from the perspective of big production facilities. This is the conventional energy world familiar to all of us. It consists of big assets, integrated systems, bulk trading, and large sales volume. Its technologies are mature and proven.

“This world still exists and will remain indispensable. In the last few years, however, a new world has grown up alongside it, a world characterized above all by technological innovation and individualized customer expectations. The increasing technological maturity and cost-efficiency and thus the growth of renewables constitute a key driver of this trend. More money is invested in renewables than in any other generation technology. Far from diminishing, this trend will actually increase.

“At the same time, the costs of some renewables technologies — such as onshore wind farms — have sunk to parity with, or below, those of conventional generation technologies. We expect that other renewables technologies could become economic in the foreseeable future.

“Renewables aren’t just revolutionizing power generation. Together with other technological innovations, they’re changing the role of customers, who can already use solar panels to produce a portion of their energy. As energy storage devices become more prevalent, customers will be able to make themselves largely independent of the conventional power and gas supply network.

“The proportion of customers that want to play a more active role in designing their energy supply is growing steadily. Above all, they want clean, sustainable energy that they can use efficiently and in a way that conserves resources.

The question for other utilities, including in Australia, is how long they can continue to marry the “old and the new” in the same organisation. As we have seen in recent months, all the three vertically integrated utilities – Origin Energy, AGL Energy, and EnergyAustralia – have recognised the threat of the “new energy” system, but downplayed its impact on their business.

They still act as though it is a threat rather than an opportunity, and the very fact of their vertical integration means that their policy position is to protect their incumbent businesses. Part of the problem is that unlike E.ON, they do not own network assets. That is for whom distributed generation makes most sense. The big assets for the Australian utilities are generators – who stand to lose from local solar and storage – and retailing, essentially packing bills for consumers.

Contrast the approach from Australian utilities with that of NRG, which could see the way that technology was changing, and decided to act before it was forced to by policy makers and regulators,

“We got sick of waiting around to see what was going to happen on the policy end,” Leah Seligmann, NRG Energy’s chief sustainability officer, told ThinkProgress last month.. “Frankly if the industry does not follow us and start moving, people are not going to have much patience with it. We can either become extinct or we can become involved.”