LIMA: Australia may be able to lift its industrial emissions by around half over the last 30 years and still be able to meet its Kyoto Protocol targets, according to new analysis released on Thursday at the Lima climate talks.

The research by Climate Analytics and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impacts Research highlights the extent to which Australia has gotten a free pass on emissions targets over the past two decades.

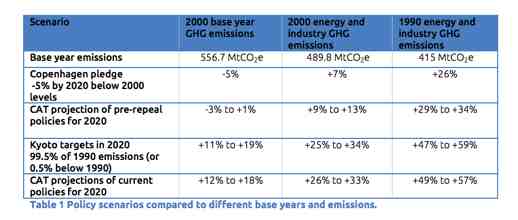

The research shows that Australia will be able to meet its legal Kyoto target: a meagre half a per cent under 1990 levels by 2020. But, in doing so, its industrial emissions will still rise dramatically. The analysis shows that national industrial emissions are likely to be 26 per cent above 2000 levels in 2020, or up by 47–59 per cent since 1990.

“Australia will be able to meet its [Kyoto] target by taking barely any action at all,’ says the report, largely because of the generous allowances it received on land use.

However, as RenewEconomy reported on Monday, in our story Australia scrambles to avoid blowout in emission targets, unless Australia can force changes to amendments made in Doha two years ago, it may not be able to meet its separate commitment made in Copenhagen to cut overall emissions by 5 per cent on 2000 levels by 2020.

As we reported, this could result in 40-90 million tonnes of Co2 abatement being disallowed. This could cause serious embarrassment on the domestic and international front, and Foreign Minister Julie Bishop has intervened to try to get the matter resolved in Lima, rather than have the issue punted to next year, as was suggested in negotiations.

Australia, as RenewEconomy flagged, Australia is putting its signature to the second period of the Kyoto Protocol on the line to protect its interests.

Whilst in Lima, Andrew Robb and Bishop kept repeating to anyone who would listen that Australia would meet its international commitments.

Australia, under successive governments, has elbowed its way through each round of climate talks to secure accounting rules in its favour, successfully pleading for special treatment on land management and baselines. And its behaviour in Lima is no different. As the graph above shows, Australia could lift industrial and energy emissions by 26 per cent and still meet its “minus 5 per cent” reduction targets. On the basis of current policy, it is likely to lift industrial and energy emissions by 49-57 per cent.

Little wonder, then, that Australia seems to be squeezing hard, trying to wring every last drop out of every legal pore in the Kyoto Protocol. Not satisfied with this, it has been attempting to redefine emissions such that it can add another 6 per cent to its allowable surplus emissions to 2020.

A really big part of the problem is that, like quantum physics, there exists only a handful of people who really know their way around carbon accounting at this level. This stuff is hard, which makes it even harder to communicate to a lay audience. Even Bishop had to refer to the delegation’s expert when a question on the subject was put to her here on Tuesday.

As the report’s lead author and CEO of Climate Analytics, Bill Hare, said: “It has become increasingly apparent that whenever Australia has talked of committing to reducing emissions, what it really means is that it will continue to increase emissions from fossil fuel and industry sources.”

To date, every independent assessment of Government’s Direct Action plan shows that it will just plain fail to arrest the rise in emissions. Essentially, it is a tax-and-spend scheme, with the funds coming out of central revenue and the spending allocation a lot, lot less than needed.

“This is just the most recent example of Australia lobbying for rules that undermine the integrity of the emissions accounting system as a whole and/or rules that carve out special exceptions to the detriment of all, but to the benefit of a few,” said Hare.

That Australia may not need to do anything to meet its Kyoto second is a situation that also prevailed for the first commitment period (2008 to 2012). The CAT has quantified emissions credits from land use activities that could result in Australia’s allowed emissions approaching or exceeding 5 per cent above 1990 levels.

“Australia’s lack of fully transparent data does not permit scientifically based verification of the published Australian Government estimates of Kyoto LULUCF debits for the second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, which are the opposite to those we estimated,” said Dr Louise Jeffrey of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

“Fully transparent data on Australian projections and estimates of future LULUCF emissions and removals are needed in order for the CAT to revise, improve and, hopefully, even reverse our estimates,” she said.

Back in the Lima conference, to a packed audience packed in a hothouse press room, US Secretary of State John Kerry held up to the heat and made a powerful call for action, saying there was no alternative to a new deal in Paris.

‘If you are a big developed nation and you are not helping to lead, you are part of the problem,’ Secretary Kerry said. ‘The science of climate change is science and it is screaming at us.’

Meanwhile, Australia won yet another Fossil of the Day Award today – its fifth in 10 days of talks – after Trade Minister Andrew Robb declared that there was no way Australia would sign on to any agreement in Paris that didn’t include its competitors.