A new report from economists at HSBC suggests European oil and gas majors such as BP, Shell and Norway’s Statoil could face a loss of market value of between 40 and 60 per cent if the International Energy Agency’s “unburnable carbon” scenario was put in place.

Last year, following detailed work by European research groups, the IEA said that if the world was to meet its climate change goals – giving it a better than even chance of limiting global warming to 2C – it needed to leave most of its fossil fuels in the ground.

Drawing on work from Meinhausen et al, it suggested the global carbon budget from 2000-2050 was only 1,440 gigatonnes of CO2. But the world had already burned 400GT. Given that the world’s proven reserves of oil, coal and gas amounted to 2,860GT of CO2, this would mean the budget would be exhausted without a significant deployment of carbon capture and storage.

The idea that fossil fuel company owners would have to leave a vast amount of their reserves – and their wealth – in the ground probably explains their antipathy, and outright opposition – to climate change policies and anything else that might slow down the use of oil, coal and gas. Though, given that few industries have been given such advance notice of their potential demise, it does seem extraordinary that comparatively little has been done to develop CCS, at least in the private sector.

Few, though, have attempted to quantify what this means for investors – even though groups such as Mercer, KPMG, have begun to raise the alarm for long term asset managers. Earlier this month, the Institute of Actuaries said the assets of pension schemes will effectively be “wiped out and pensions will be reduced to negligible levels” if investors continued to ignore resource constraints and climate change issues.

HSBC, which had a quick look at the coal sector last June, have now crunched the numbers for the oil and gas industry – or at least the European sector.

It says the greater risk to market value does not necessarily come from leaving stuff in the ground, because the market already applies a discount to undeveloped resources. Still, in the case of Norway’s Statoil, unburnable carbon reserves could amount to 17 per cent of market capitalisation. In the case of British group BG, it would be less than one per cent.

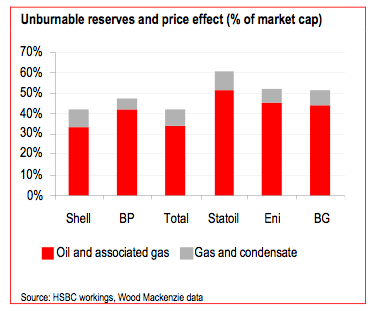

The biggest impact, says HSBC, will be on lower prices caused by reduced demand for their product, particularly oil. In this case, HSBC says, up to 60 per cent of the value of fossil fuel companies could be lost, as this graph below illustrates.

“Because of its long-term nature, we doubt the market is pricing in the risk of a loss of value from this issue.” the HSBC economists say. Indeed, we can only think of one other analysis, a smaller one done by Citigroup a few years ago, which looked at Woodside and Coal and Allied.

Such impacts may not be that far away. The IEA said in 2011 that the world could exhaust its carbon budget by 2017 if it continued unabated. A year later, it said focusing on energy efficiency could deliver a further 5-year window. Either way, the crunch could occur in the next decade.

“We believe that investors have yet to price in such a risk, perhaps because it seems so long term,” the HSBC economists write. “And we accept that our scenario probably exaggerates the risk as we assume a low-carbon world today rather than beyond 2020. However, we believe it does give an indication of the potential impact on the sector. “

HSBC says reductions in oil demand can be delivered more quickly than coal through improvements in transport fuel efficiency.

Under the IEA low carbon scenario, demand for coal would fall by 30% between 2010 and 2035 and oil by 12 per cent. Gas would not be as affected, but it would grow more slowly.

HSBC says that in this low carbon scenario, projects would be deferred or cancelled – and the first victims would be those with high costs. For oil projects, anything about $50 a barrel would struggle – that would include oil sands, some deep water plays and some US share oil projects – and presumably Australian shale oil projects such as the recently announced Linc Oil discovery.

For gas, the economic limit is put at $9/mmBtu (british thermal units, a measure of gas – it is equivalent to around $55/barrel). That could also put some future Australian gas developments at risk, given the predictions of the course of Australian gas prices.

The report’s analysis on stocks focuses on European oil majors. It says up to 25 per cent of BP’s proven and probably reserves would fall into its unburnable carbon category, equating to around 6 per cent of its market value.

Statoil’s unburnable carbon reserves amount to 17 per cent of its market capitalization, because it has a higher ratio of high-cost traditional projects in Norway. At least half of these are at risk

HSBC says oil is more effected than gas because its consumption is easier to reduce, as it is mostly used in transport, and the transport sector could more readily reduce its consumption.

For instance, it notes that India has a fuel efficiency of 6 litres per 100km for cars, compared with 9L/100km in the US. “Many passenger vehicles appear to hav been designed to be deliberately inefficient,” it says, because power and speed sells more cars than efficiency.

But this is changing, and even the new hybrid version of the Enzo Ferrari cuts emissions by 40 per cent, and new economy standards are being introduced in the US.

Ultimately, though, HSBC notes that the fate of many of these reserves lies in the hands of the governments and state-owned companies that control 70 per cent of the world’s proven oil reserves and 90 per cent of the world’s combined oil and gas reserves.

But for safety sake, HSBC says investors should focus on companies with low-cost future projects. Capital-intensive, high cost projects such as heavy oil and oil sands, are most at risk under its scenario.