Yesterday’s main article about the frustrations and the barriers being put in front of Australia’s effort to meet its 20 per cent renewable energy target was followed this morning by yet another aggressive push by the major utilities to have the support mechanisms for large-scale wind and solar developments removed or diluted.

The Australian Financial Review had as its front page lead, and several articles and commentaries inside, the story of how Origin Energy and Energy Australia, amongst others, had declared the renewable energy target to be both expensive and unachievable, particularly in light of the early move to a traded carbon price.

The utilities did not make it clear how a one-year change in the traded carbon price can affect a target that was framed before a carbon price was even put in place, let alone suddenly make it that much more expensive. Nor did it occur to the editors of the national business daily that the primary purpose of this intensive lobbying may be to protect the revenues of the incumbent assets of the energy industry. That, at least, would have been worth a mention to insert some context. The industry has already admitted some $4 billion of revenues are at stake.

But as the electricity incumbents continue to circle the wagons around their threatened business models, the renewable energy industry may be able to take comfort in some good news: Australia may be able to meet its 20 per cent renewable energy target by 2020, and go beyond that, simply because renewables will represent the cheapest option as the electricity industry looks for new generation and is forced to replace ageing and redundant capacity.

Kobad Bhavnagri, the Australia head of Bloomberg New Energy Finance, told the Clean Energy Week conference on Wednesday that renewables could supply 46 per cent of Australia’s electricity by 2030, compared to around 12 per cent now, and the official target of a minimum 20 per cent target by 2020.

How would this be achieved? Well, according to BNEF, large-scale solar – mostly PV – will account for around 17GW (17,000MW) of installed capacity. That compares to just 10MW now. This does not include at least 10GW of rooftop solar – compared to around 2.5GW now. BNEF expects wind energy to account for around 12.5GW, although it expects wind’s share in new investment to diminish rapidly from around 2017 as it is overtaken by solar PV.

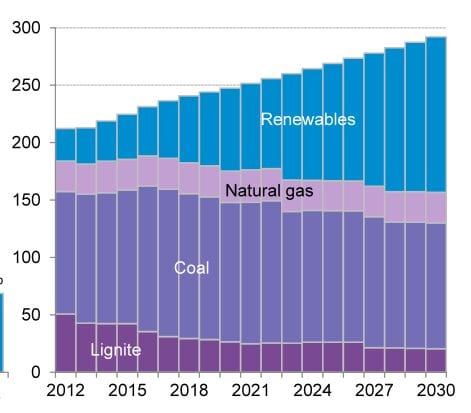

Here’s the graph to illustrate BNEF’s vision of the energy mix by 2030.

Costs are the critical part of the equation, because most of Australia’s existing capacity will need to replaced in coming decades, and the choice will be based around which technology is the cheapest to build new plant. The incumbent generators are concerned because they know that wind and solar make poor bedfellows with inflexible fossil fuel generators, and that an increased penetration of renewables will force many coal generators to close early.

BNEF notes – as can be seen in the first graph – that gas generation will also be too expensive, and its share of the electricity generation capacity will actually fall, as there is already enough capacity to deal with the variability and intermittency of renewables. And in any case, Bhavnagri says, developments in battery technology means “storage is coming faster than most people would think.”

BNEF says solar modules will continue to fall in price by 25 per cent for every doubling in global capacity, while wind generation will fall around 14 per cent for every doubling in capacity. The conclusions are an extension to their earlier study, which noted that wind is already cheaper than new coal and gas, and solar will be there soon.

Here are the latest graphics on costs: on wind ….

and solar ….

The issue of cost means that over the long-term there is little that the incumbent gentailers – the companies who own conventional generation and also act as retailers, packaging up bills to customers – can do about it, short of convincing the government of the day to consider banning wind and solar developments. (OK, so let’s not rule that out.)

That’s because, as Oliver Yates, the head of the Clean Energy Finance Corporation pointed out, developers and financiers will start to take matters into their own hands, and start looking to the “merchant market”, which means they will no longer wait for a utility to write a power purchase agreement (PPA) for a wind or solar farm to be built, and will finance it themselves.

Yates said the traditional view of the banks was to say ‘no PPA, no deal’. And utilities have been reluctant to sign PPAs because of “policy uncertainty” and because of the surplus of renewable energy certificates. “I think the banks are getting comfortable with the idea that they don’t need a PPA,” Yates told the CEW conference. “They have got to think creatively.” Yates noted, for instance, the growing interest in the use of mezzanine finance to fill the financing gap. But this still required, he said, the certainty of the fixed 41,000GWh target.

However, a merchant market does rule out many potential developers because they do not necessarily have the financial muscle to accept their share of the financing risk. And the utilities would be happy to pass on some of this risk to the developers. So to a certain extent, this plays into the hands of the incumbents.

But there is a another growing influence, which is consumers, who are also taking matters into their own hands. We have seen this with households and businesses looking to install solar to cater for their own needs; and last week Sunshine Coast council became the first significant large user to propose a utility-scale development of its own – saying it would build a 10MW plant to satisfy half of its own electricity needs. It doesn’t much mind what the retailer thinks.

This will be accompanied by the likes of SunPower and other aspiring providers and technology developers entering the home services market, offering 100 per cent clean energy at cheap rates. The energy retailer industry has been notoriously difficult to crack – Pacific Hydro and Infigen Energy are also having a go – but the home energy service” market, where providers enter the home and offer different services, rather than just delivering a bill to the letter-box, could provide a breakthrough.

This is what makes the future of the electricity industry over the next two decades so fascinating – does it remain a centralised, hub-and-spoke model, or does it move to the distributed model predicted by many? Can the circle of wagons drawn around the incumbent model successfully protect existing interests, or will it be pulled apart by the plunging costs of new technologies and new ways of thinking about the delivery of electricity.

The utilities remain deeply attached to the conventional, centralised model of generation and are guarding their remaining assets, hoping that by attacking the carbon price, the renewable energy markets, and even the regulatory rules and market design, they can protect their assets, or at least lift the wholesale price.

One issue is a resuscitation of the “contracts for closure” payments. Even Chinese wind developer Goldwind came out in support of a revival of the program, where large coal plant owners are paid by the government – or through a levy on consumers – to close their plants early. This is crucial for utilities to protect their revenues – some of them actually have job titles such as manager for revenue protection – and to underpin the wholesale price, but it seems that some of the larger renewables developers still rely on utility contracts. They appear as blind to progress of solar PV and distributed generation, which will surely push out “second tier” wind projects if the BNEF data and forecasts are right.

Another issue raised by the utilities, and others, is the scenario where retailers choose to pay a “penalty price” on renewable energy certificates rather than causing new generation to be built. This has been raised in the past by Origin Energy, suggesting it would be embarrassing for the government to have to explain why people are paying extra in their bills for renewable generation that is not being built.

Or it could be embarrassing for utilities to explain to their consumers why they didn’t build it in the first place. The likelihood is, though, that the costs of technology will come down faster than they realise, and unless the wholesale price falls to near zero, solar at least will be built, and consumers will find ways of cutting out the middle men – the networks and the retailers – and the huge costs that these add to bills. As the largest utilities in the US are concluding, they risk being “disintermediated” out of the market

As Bhavnagri says: “The only certainty is that the future won’t look like the present.” That will not prevent, however, the incumbents using their political muscle and lobbying power to extend the present as far into the future as they can.