Over the last couple of days, wind energy has experience a short “drought” in most Australia states, but it is nothing compared to the drought of new connections and registrations of large scale wind and solar projects in the country’s main grid.

Buried in the detail of the most recent quarterly report from the Australian Energy Market Operator was this bleak assessment: “There were no projects registered and connected to the NEM (National Electricity Market)” in the first quarter of 2024.

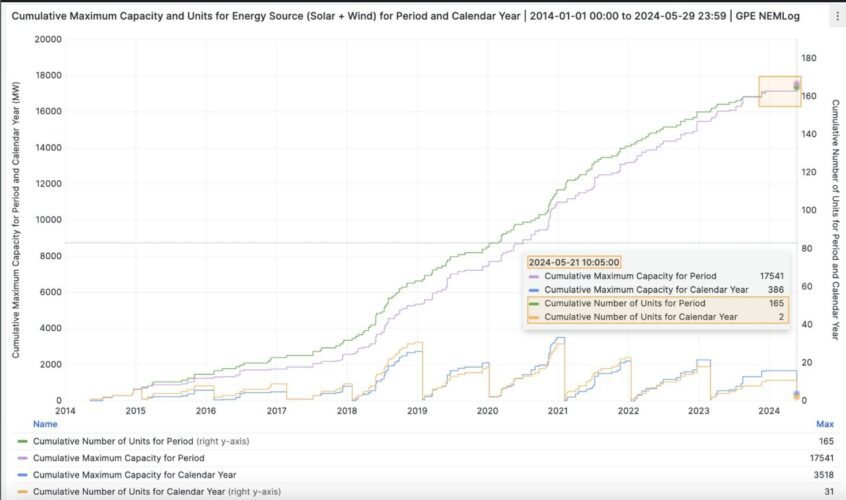

That drought – at a time when the country needs an extra 6 GW of new capacity a year to reach its 2030 renewable energy target of 82 per cent – continued until late May when the 56 MW Crookwell 3 wind farm and the 330 MW Wellington North solar farm both entered AEMO’s management system, known as MMS, on May 21.

According to Geoff Eldridge, from data collector firm GPE NEMLog, these were the first projects entering the commissioning pipeline on Australia’s main grid since the Mannum 2 solar farm in South Australia in mid-December.

Another big project has since been added to the MMS, with the introduction of the 200 MW, two hour Western Downs battery in Queensland, located next to Neoen’s 400 MW solar farm.

According to Eldridge, it is the longest drought in new wind and solar projects since 2014, when Tony Abbott was prime minister, bent on ditching the carbon price and trying to scrap the renewable energy target, and the agencies that went with it.

It’s not the only piece of data that paints a grim picture of the current pace of the green energy transition in Australia, despite all the big announcements and plans for the future.

The Clean Energy Regulator says just 56 MW of new capacity was approved to generate renewable energy certificates in April, with the biggest being the 11 MW Robertson Barracks solar system in the Northern Territory, which was actually built years ago but until now was one of a handful of solar projects prevented from joining the local grid.

All of the other projects approved by the CER in April were small ground-mounted solar systems, or large rooftop solar systems, confirming the story of the last few years that it is consumers – be they household or business – that are getting on with the job of installing new capacity.

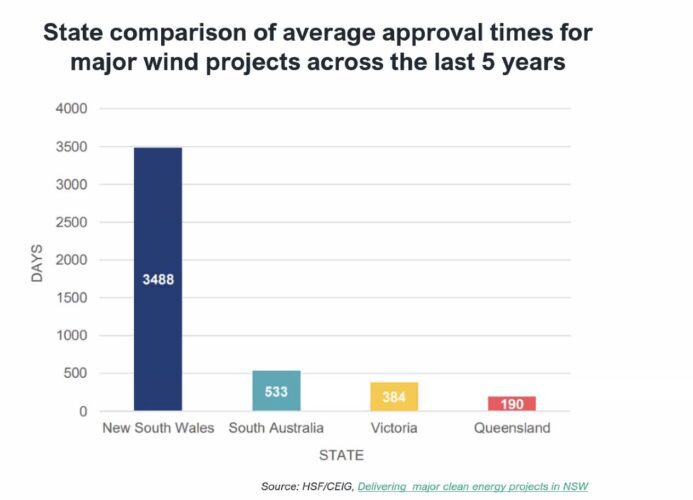

Large scale systems have been stalled by a myriad delays – in planning approvals, connections, and commissioning, and policy and market uncertainty.

The planning approval delays have been particularly bad in NSW, where IEEFA’s Amandine Denis-Ryan noted in a webinar hosted by Renew Economy this week, wind projects have taken nearly 10 years to get through the planning system.

The impact of those delays is already being felt, with the closure of the Eraring coal fired power station in NSW, at 2.88 GW the biggest in the country, put off for at least two years and possibly four because of the lack of new capacity in the grid.

Its owner Origin Energy has completed no new large scale renewable projects since flagging the early closure in early 2022, and other project developers have been unable to get going fast enough.

It’s not as though there is no queue. According to AEMO’s quarterly report, there was 41 gigawatts (GW) of new capacity progressing through the end-to-end connection process from application to commissioning at the end of the March quarter, up 70 per cent from a year earlier.

But the total number of “proposed projects”, including those who have yet to enter the connection process, totals more than 250 GW, according to AEMO’s most recent Generation Information data.

That pent up demand was reflected in the 19 GW of applications for just 600 MW of four-hour storage capacity on offer in Victoria and South Australia as part of the new Capacity Investment Scheme.

It is hoped that the CIS can, in fact, unlock that pipeline and open the doors for at least some of the projects queued at the gate. Its first tender of 6 GW of new wind and solar is opening this month, and will be followed by similar sized tenders later this year and next.

In all, the federal government is targeting 23 GW of new wind and solar capacity and 9 GW of storage capacity to be tendered so they can be built by 2030. Analysts such as Denis-Ryan say that target for wind and solar should be lifted from 23 GW to 36 GW to ensure that the renewable target is met.

But one of the issues is that new developments – with the exception of some of the largely “behind the metre” projects for large customers, such as the gigawatt scale wind and solar deals proposed by mining giants Rio Tinto for its smelters and refiners – are now captive to the CIS process.

Indeed, it has been argued that the CIS process itself has slowed recent developments because potential off-takers and developers have waited to see what they can achieve in that auction process before moving forward with their projects.

The federal Coalition, on the other hand, wants to scrap it all – demanding that all new wind and solar projects be brought to a halt, and has even threatened to tear up contracts with the federal government.

It has made clear it thinks coal fired power stations should be kept open until the first nuclear plants can be delivered, likely to be in the early 2040s. Most in the energy industry point out that would be a disaster for emissions, costs, and grid reliability.