The lack of any policy to meet the climate targets agreed to in Paris will mean that Australia’s large-scale wind and solar boom will quickly come to an end, even as wind and solar costs fall further below the benchmark price of the grid.

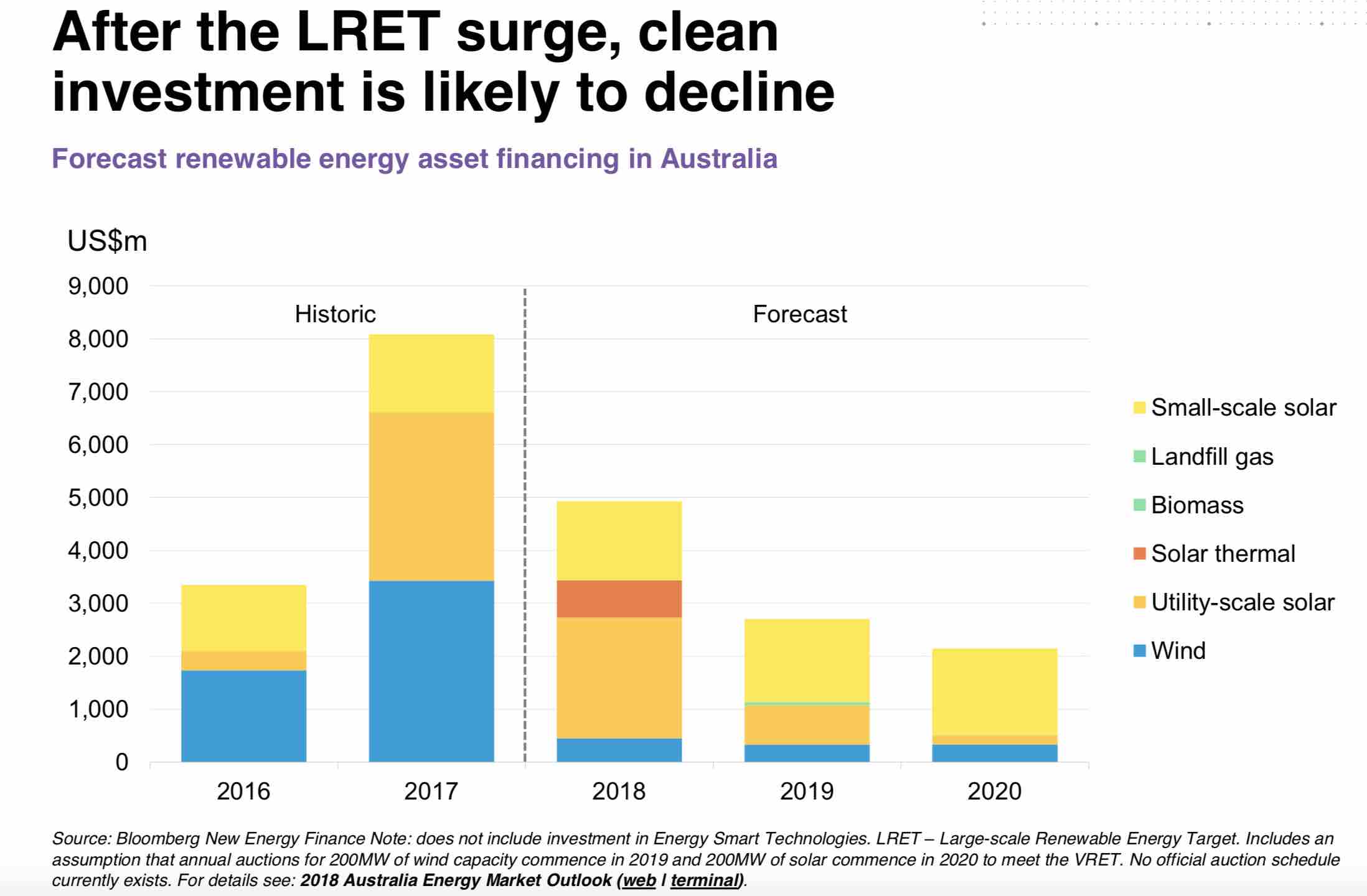

Kobad Bhavnagri, the chief analyst for Bloomberg New Energy Finance in Australia, says the current investment boom to meet the federal renewable energy target – $8 billion committed in 2017, and $5 billion in 2018 – will quickly slow as the target is met.

By 2020, investment will slow to around $2 billion, and for the next decade – without any changes to stated federal policy – the only drivers for the uptake of large-scale renewables will be state schemes, such as Victoria’s, and the emerging corporate market.

The proposed National Energy Guarantee, Bhavnagri says, will add little to demand because the 26-28 per cent emissions reduction will be met almost entirely by the LRET by 2020 (23 per cent), leaving little to be done over the next 10 years.

“That’s a very weak target,” Bhavnagri said, noting that according to his company’s analysis, it will mean less in the way of new wind and solar capacity by 2030 than business as usual. (See chart above)

Bhavnagri said this would be true whatever the policy – a carbon price, an emissions intensity scheme or a clean energy target; if the ambition is low, then little new renewables would be built because there would be no driver to displace existing coal and gas.

And it is clear that the current government has every intention of trying to keep existing power generators, including ageing coal plants, in the system as long as possible, dramatically reducing the need for new supply.

This bleak assessment is broadly consistent with other analyses, most notably by Reputex, which also said last month that the emissions reduction target is actually worse than business as usual.

However, Bhavnagri said there re a couple of factors that should be cause for optimism for the renewables industry, and this was based largely around economics.

It was clear now, he said, that the cost of new renewable – large-scale wind and solar – was already below wholesale electricity prices.

Wind and solar were being built at or around $60/MWh, and would continue to fall in cost in the coming five years.

After a brief fall in wholesale prices as the current surge in wind and solar investment had its impact on the market, the course of wholesale prices would then resume their upward curve.

This meant that wind and solar would be attractive, not just for big utilities looking to loosen their reliance on fossil fuels (Origin has pledged an exit from coal by 2032), but also for the growing corporate market.

On the subject of policy choices, amid all the criticism of the proposed NEG, Bhavnagri said that if it was accompanied by meaningful remissions reductions targets, then it would do the job.

“What really matters is ambition,”Bhavnagri said. “If the NEG were to be configured to 45 per cent, recommended for 2°C pathway, which has been adopted by Labor, the outlook for investment would be much stronger.”

As this graph above illustrates, that would result in 1GW less coal, but 4GW more large-scale wind, and 10GW of large-scale solar – according to BNEF’s estimates.

The only constant through the two scenarios (ambition or no ambition) is small-scale solar – which BNEF expects to add at least 1GW a year out to 2030 – taking the total installed capacity across the nation to 19GW by 2030, overtaking coal.

“What about the NEG? The answer to that, quite simply, is that Malcolm Turnbull needs to grow a spine on this particular issue, if it’s going to be meaningful,” Edis said.

But, as John Grimes, the head of the Smart Energy Council said, there is just no chance of that anytime soon because of the secret deal that Turnbull signed with the far right when they agreed, reluctantly, to have him replace Tony Abbott.