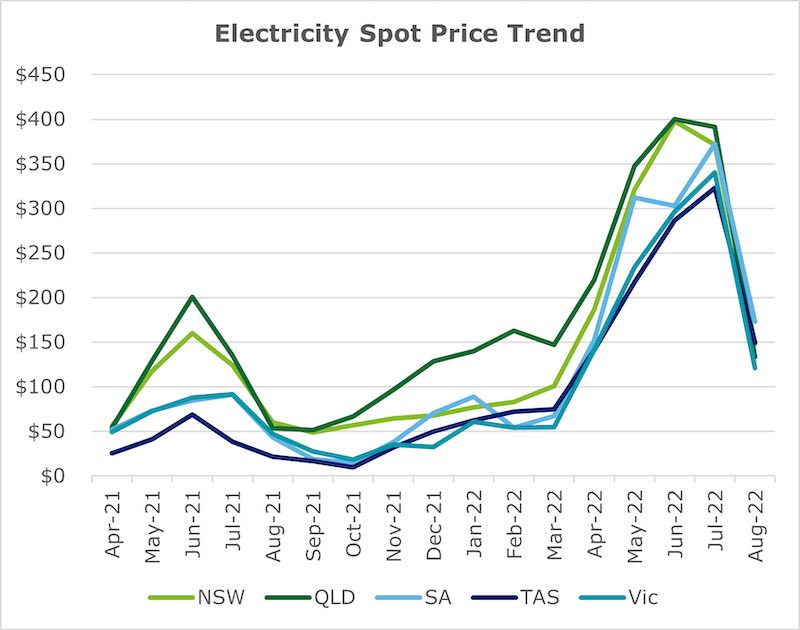

Never before has Australia seen energy prices in the wholesale market spike like they have over the last five months.

Between May and August 2022, average wholesale prices in the National Energy Market (NEM) states have increased by 324% compared with the same period last year ($282 per megawatt-hour (MWh) in contrast to $87 per MWh in 2021).

At the height of this unprecedented volatility, the Australian Energy Market Operator stepped in – for the first time – and suspended the wholesale market for a week.

Amid this very elastic situation, industry participants were left wondering where all this was going, and looking for policy reforms and perhaps wholesale (excuse the pun) restructuring of the market.

And all that’s before sparing a thought for energy consumers.

Energy retail customers and small business owners could be forgiven for being both concerned about massive electricity price rises, while also quietly confident that price rises are ‘constrained’ by regulation.

The ceiling or the floor?

The default market offer (DMO)/Victorian default offer (VDO), also known as the reference price or the ceiling price, is described by the Australian Energy Regulator as the “safety-net price cap that ensures consumers are protected from unjustifiably high prices”.

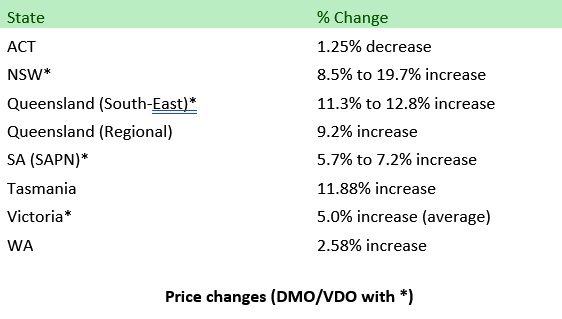

The DMO/VDO increases from 1 July 2022 (with different impacts in different states) appeared not so bad compared to rises in the wholesale market.

But the impacts belie an uncomfortable truth for many energy consumers – the DMO/VDO is applicable to no more than 7% to 16% of residential and small business customers.

As a result, most consumers are on competitive market offers – exactly the outcome policy makers have been aiming for since full retail contestability was adopted in the NEM states.

When energy prices are stable – or even falling – and there are many energy retailers to choose from, shopping around for the best energy deal is easy, and the astute consumer can save hundreds of dollars a year.

However, prices aren’t stable and consumers on competitive market offers are watching their rates rise much higher than the DMO/VDO.

Retailers are not obliged to sell electricity to customers at the default rates, so many are not. Some are, in fact, increasing their prices dramatically by as much as 285%!1

Consumers are finding that the lowest rates on offer are, in fact, the DMO/VDO. Many consumers have been searching for better deals on the government-run comparison websites (Victorian Energy Compare and Energy Made Easy, which facilitate easy switching to the best energy deals in the market, normally saving consumers hundreds of dollars a year).

Now, this search will show very little difference between the DMO/VDO and the best offer. In fact, many offers on these sites are much more expensive.

It’s an upside down world where the previous ceiling has become the floor price.

A perfect storm for retailers

While energy retailers have different hedging strategies and most are – to some degree – protected from the direct ravages of the spot price, many have at least some exposure.

For consumers, retailers are like an insurance policy – protecting them from the extremes of day-to-day wholesale price changes. However, just like insurance, with greater variability comes increased premiums.

Smaller retailers without their own generation capabilities are feeling the downside of this dynamic the most. The DMO/VDO has not risen to levels to provide enough revenue to recoup their costs – let alone make a profit.

As these retailers are effectively resellers, they are being squeezed. Some have already gone out of business, while others are trying to reduce the number of customers to limit their wholesale exposure.2

The UK market is a good indication of what can happen. In 2021, Britain experienced similar dynamics, with half of Britain’s electricity retailers exiting the market or put into administration, affecting around one in six customers.

The impact of this structural dynamic means that competition was lowered. Like the insurance industry, premiums are going up to recoup current and perceived future costs.

So, what can be done?

The good news is that the forward futures price curve is showing a gradual decline in wholesale prices, albeit this is heavily dependent on the government’s commitment to intervene in the gas market and redirect exports to the domestic market.

In other words, the outlook for future pricing, and relief for consumers, is contingent on the government’s reform agenda and the speed with which this can be achieved.

However, the government’s commitment to a 43% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 and also the federal, state and territory energy leaders’ agreement to dump the Energy Security Board’s model for a proposed so-called “capacity mechanism” (which could have possibly aided energy reliability – and put downward pressure on prices) could mean high(er) energy prices may be here for a lot longer.

Industry regulators are ‘stress testing’ energy retailers to ensure their viability to participate in the market. Energy retailers should be ready to:

– Demonstrate their ability to deal with ongoing volatility in wholesale markets.

– Minimise current debt and have provisions for large, unexpected debts.

– Demonstrate in-depth knowledge of their vulnerable customers.

– Provide easy self-service payment arrangements to deflect voice contact.

– Pay attention to customers who don’t respond as they may include customers who are struggling the most.

Uncertainty around prices is very much a part of Australia’s energy transition (which is now in full swing) and an inevitable by-product of the turbulent pathway towards rapid decarbonisation of the electricity sector (which is responsible for 36% of emissions).

Australia is experiencing the pitfalls of delaying energy reform and not approaching the transition in a planned manner – and that’s before allowing for potential global market shocks.

Domestic consumers, residential and business alike, will have to accept fluctuations in energy prices as we navigate the energy transition ahead. Gone are the days when a price ceiling means anything. Perhaps it was a glass ceiling all along and aren’t glass ceilings meant to be broken?

Simon Vardy is a consulting partner at Deloitte with more than 25 years’ experience in the resources, utilities and professional services industries.

1. Joel Gibson from consumer advocacy One Big Switch quoted here.

2. NOTE – this author’s own retailer has sent him numerous emails and texts advising him to switch to another retailer. They also advised that if he didn’t switch, his tariffs would go up by 82%.

This article was originally published by Deloitte, republished here with permission.