Researchers from the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) say they have developed a new material for use in the construction of wind turbine blades that is both bio-derivable and easily recyclable.

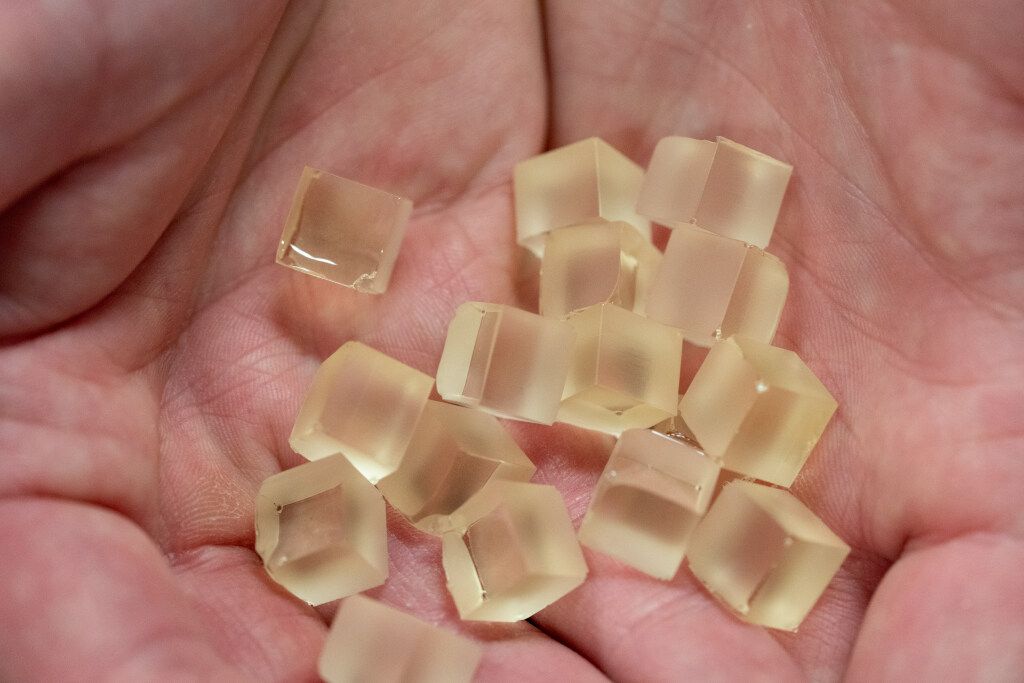

The NREL researchers believe the newly developed resin, made from materials produced using bio-derivable resources, paves a “realistic path” towards the manufacturing of wind blades that can be chemically recycled and the components reused, ending the practice of old blades winding up in landfills at the end of their useful life.

Importantly, the new resin – nicknamed PECAN for PolyEster Covalently Adaptable Network – can be dropped in to current manufacturing techniques, avoiding the need for completely new manufacturing lines or production techniques.

While there already exist several methods for recycling wind turbine blades, these are time and labour intensive, making it a less than attractive option for some operators, leading to the much-hyped fear of landfills filled with turbine blades.

PECAN, however, could revolutionise the recyclability of wind turbine blades, requiring only the use of mild chemical processes.

The researchers built a prototype 9-metre blade to demonstrate the manufacturability of PECAN and which helped them to demonstrate an end-of-life strategy for the blades which included recovery and reuse strategies for each component used in its construction.

According to Ryan Clarke, a postdoctoral researcher at NREL, the chemical recycling process was able to break down the prototype blade in only six hours. Further, the recycling process allowed the components of the blades to be repeatedly recaptured and reused, allowing for the remanufacture of the same product.

The new resin – which is made using bio-derivable sugars – also disproved the idea that a turbine blade designed to be recyclable is inherently less durable.

“Just because something is bio-derivable or recyclable does not mean it’s going to be worse,” said Nic Rorrer, one of the two corresponding authors of the paper, which was published in the journal Science.

According to Rorrer, concerns about these bio-derivable or recyclable materials is that the blade would be subject to “creep” – when the blade loses its shape and deforms over time.

In fact, composites made from the PECAN resin were able to hold their shape, withstand accelerated weatherisation validation, but can still be made within a similar timeframe to the existing cure cycle for how wind turbine blades are currently produced.

“It really challenges this evolving notion in the field of polymer science, that you can’t use recyclable materials because they will underperform or creep too much,” said Rorrer.

The 9-metre blade was also able to “demonstrate all of the same manufacturing processes that would be used at the 60-, 80-, 100-meter blade scale,” according to Robynne Murray, the second corresponding author.