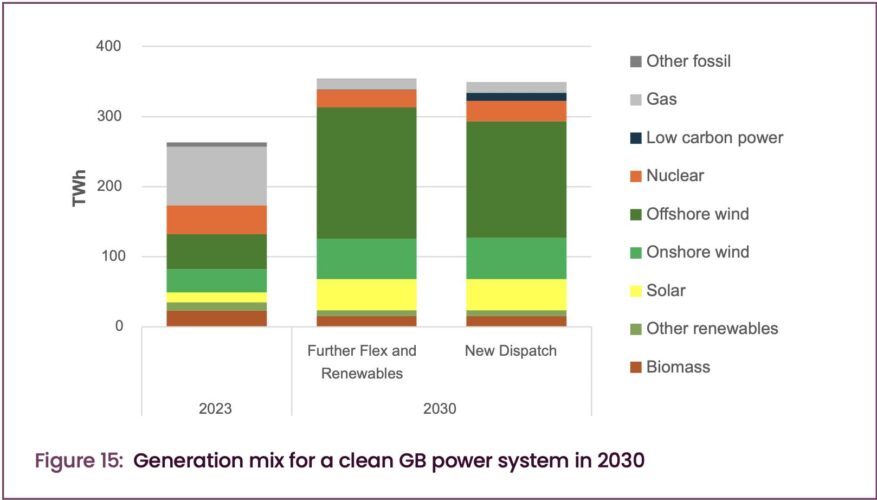

The system operator for the United Kingdom’s electricity grid has released its pathways to reach a “clean energy system” by the end of this decade, and it involves a three-fold increase in wind and solar capacity and a significant decrease in nuclear.

The National Energy System Operator (NESO) presents two pathways to achieving Clean Power by 2030 which it defines as reducing fossil fuel services to less than five per cent gas, and exporting more than it imports.

Both include significant increases in renewables, mostly offshore wind in one scenario, and with a greater share of onshore wind and solar in the other.

“We present two main pathways to clean power in 2030. Both involve increased electrification of heat, transport and industry – a reductionist approach that slows down electrification to lessen the challenge of clean power would undermine the core objectives of cutting energy costs and supporting net zero,” it says.

“One pathway, Further Flex and Renewables, sees 50 GW of offshore wind and no new dispatchable plants. The other, New Dispatch, has 43 GW of offshore wind and new dispatchable plants (totalling 2.7 GW, using either hydrogen from low carbon sources or carbon capture and storage (CCS).”

However, the real significance of the document is that the pathways include no new nuclear power capacity, despite the fact that the UK is an established nuclear power and operates several nuclear power plants. In fact, the assumed nuclear power capacity will fall by up to 43 per cent by the end of the decade.

This, of course, is contrary to the story spun out by nuclear boosters in Australia and elsewhere. But for all the talk about a global nuclear renaissance, it is not really happening – and any increase in construction in some markets is being dwarfed, more than 100 times over, by new investments in wind, solar and storage.

The NESO conclusions are no real surprise to most energy experts, even if they would be deflating for many Australian nuclear ideologues, many of whom advocate a complete halt to the rollout of new wind and solar, an extension to ageing coal fired generators, and a greater dependence on gas.

The only nuclear plant to begin construction in the UK in recent decades has proved to be a complete financial disaster. Hinkley C was supposed to be finished and roasting turkeys by 2017, according to initial boasts by its French manufacturers EdF.

But it will now not likely be completed before 2031, and at an eye watering cost of up to $A92 billion, roasting an entirely different set of turkeys imagined by the former head of EdF. And it may cost more and be further delayed.

Meanwhile, a new report from the UK National Audit office says the cost of waste management at the soon to be decommissioned Sellafield nuclear plant has now blown out to £136 billion ($A267 billion).

And despite all the talk of small modular reactors, including from the UK company Rolls Royce, NESO is not impressed, saying the technology would add overall costs to the system, and have little impact in reducing the already small amount of unabated gas assumed to be in the system by the end of the decade.

“Including 1.8 GW of additional firm capacity in 2030, such as from nuclear small modular reactors, would provide around 13 TWh of generation and reduce the share of unabated gas by 0.9 percentage points (3 TWh),” it says.

“Much of the remaining 10 TWh would be lost to curtailment or exported at low cost, implying an increase to overall costs of the power system.”

That added wastage, and extra costs, would be particularly significant in Australia, where any “firm capacity” needs to be flexible enough to dance around the growing share of rooftop PV, still being installed by households and businesses at record levels. And Australia, as a whole, cannot export to another grid.

NESO says its pathways were developed from the analysis set out in its Future Energy Scenarios, with adjustments based on the greater challenge of clean power, our deeper assessment of the 2030 pipelines and our stakeholder engagement for this report.

It follows a similar process to the Australian Energy Market Operator’s Integrated System Plan, and comes to largely the same conclusions on the benefits of renewables, albeit with a different technology mix because of the two countries’ respective wind and solar resources

“Stakeholders encouraged development of a wider set of sensitivities and emphasised the importance of some technologies for the period beyond 2030, even where their 2030 role is limited,” it said.

“Based on feedback and our pipeline analysis, we reclassified a proposed pathway with 55 GW of offshore wind as a sensitivity and added a further sensitivity with more new dispatchable generation.

“Our clean power pathways push the limits of what is feasibly deliverable, but there are some flexibilities at the margin. For example, onshore wind and solar could substitute for offshore wind; more demand-side response could substitute for batteries; more hydrogen or CCS could substitute for most other supply options.”

The UK’s secretary of state and net zero Ed Milliband says defeatists should take note of the NESO report.

“It is conclusive proof that clean power by 2030 is not only achievable but also desirable, because it can lead to cheaper, more secure electricity for households, it breaks the stranglehold of the dictators and the petrostates, and it will deliver good jobs and economic growth across this country in the industries of the future,” he wrote in The Guardian.

“We are going to build the energy projects we need across the country – windfarms, solar farms and, yes, new grid infrastructure. In doing so, will get our country off the rollercoaster of volatile fossil fuel markets so we can deliver cheaper electricity.

“We know there are trade-offs when we build new infrastructure, and we will work with communities so local people feel the benefit. But we don’t shy away from making these pro-energy security, pro-growth, pro-climate decisions.”