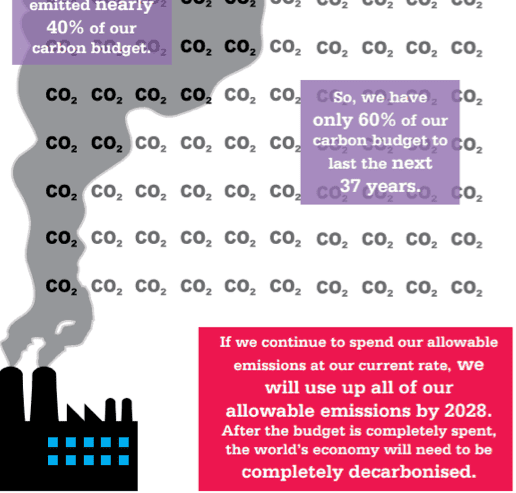

Scientific consensus on anthropogenic global warming is stronger than ever; greenhouse gases have reached the highest level in over one million years and continue to climb at the fastest rate on recent record; and the world is rapidly squandering its dwindling carbon budget – the allowable amount of greenhouse gases we can emit over the next 36-odd years to have any hope of restricting global warming to 2°C and thus limiting ‘dangerous’ climate change.

That’s the rub from the Climate Commission’s latest report card, The Critical Decade 2013: Climate Change Science, Risks and Responses – a comprehensive document that sets out the scientific basis for urgent action on climate change, reminds us of the risks for Australians, tracks our progress – and warns that we’ve got some serious work to do.

The report, written by Professors Will Steffen and Lesley Hughes, is an update of the Commission’s equally comprehensive 2011 report, the first to describe the 2011-2020 period as the “critical decade” to begin decarbonising Australia’s economy and reducing the risks posed by climate change.

Two years on, says the report, many of the risks scientists warned us about are now playing out: “Climate change is already having a significant impact on Australians and people around the world… through its influence on extreme events, on human health, agriculture, fresh water supplies, property, infrastructure, and the natural ecosystems upon which our economy and society depends.”

In Australia, heatwave, bushfire weather, drought conditions and heavy rainfall events have become more frequent and forceful, the report says. And now, further risks are being predicted.

“Changi

But the good news – and the main take-away message from the report – is that it is still possible to keep global temperature at “manageable levels,” if – and it’s a big if – global efforts, including from Australia, accelerate.

A big part of this accelerated effort, says the report, will mean “major changes to the ways in which energy is produced.” And one of the most major changes – one that was recently flagged by the IEA – is that most of the world’s known fossil fuel reserves will have to be left in the ground.

As the IEA has also pointed out, the current amount of carbon embedded in the world’s indicated fossil fuel reserves (coal, oil and gas) would, if burned, emit an estimated 2,860 billion tonnes of CO2 – nearly five times the allowable budget of about 600 billion tonnes of CO2 scientists say we can emit to 2050 for a 75 per cent chance of limiting temperature rise to 2°C.

As it is, says the report, “the rate at which we are spending the (carbon) budget is still much too high.” Under a business-as-usual scenario, scientists say we are on track to have spent it by 2028, at which point we could emit no more and the world economy would need to be completely decarbonised.

For Australia, this means leaving most of its thermal coal in the ground. But this is no longer such a radical concept – even corporates and energy producers such as AGL Energy have proposed a tight carbon budget for Australia.

The report does, however, point to some promising signs that steps are being taken towards decarbonising the global economy in a somewhat orderly fashion. “Renewable energy technologies are being installed at increasing rates in many nations. The world’s biggest emitters – China and the United States – are beginning to take meaningful actions to limit and reduce emissions,” it says.

“However, the rapid consumption of the carbon budget, not to mention the discovery of many new fossil fuel reserves, highlights the enormity of the task. Much more needs to be done to reduce emissions… and quickly.”