West Australia’s regional utility Horizon Power has become the first major Australian utility to embrace the concept of “base-cost renewables”, recognising that the plunging cost of solar and wind is set to turn traditional theories of energy supply on their head.

Horizon boss Frank Tudor has outlined a vision that he says will be an R&D “sandbox” for bigger and more centralised utilities across the country – and the world.

And it’s about shifting to a future of “distributed energy”, built around low-cost renewables and enabling technologies like storage and smart controls to fill the gaps.

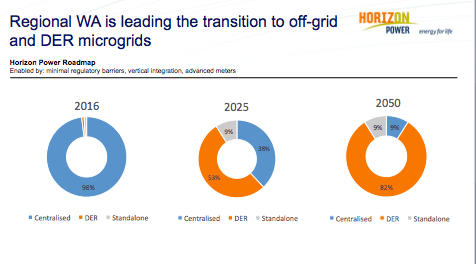

Horizon’s own vision is to provide 82 per cent of its supply in the form of distributed generation by 2050, a massive shift from the conventional view that all customers should be served by centralised generation and fed by long networks of poles and wires.

The concept of “base-cost renewables” is being championed by Bloomberg New Energy Finance to reflect the plunging cost of solar and wind, and to replace the traditional concept of “baseload” and peak plant.

The idea is to build the grid up from the base by using these cheap renewables, and then adding in storage and other smart technologies such as demand response and energy efficiency to fill in the gaps.

This idea is getting stronger support now that it is clear that the cost of solar has already fallen to below 2c/kWh in places like Mexico and the Middle East, and will soon follow elsewhere.

UNSW professor Martin Green says 1c/kWh solar will likely be reached by 2020 – making the idea of burning coal when the sun is shining completely redundant, or even insane given its environmental impacts and the lack of flexibility in coal-fired technology.

Tudor also thinks that 2c/kWh solar will reach Australia soon enough. “The marginal cost of generation will be close to zero” he says, and adds Horizon is well placed to benefit from this.

Tudor says while it will result in a wholesale cost much reduced from today, it must also translate into reduced costs for consumers. The distributed model seems to be the best way to deliver that.

“It’s a paradigm change …. we are turning the model on its head,” Tudor says.

Tudor describes the future as “distributed, decarbonised and digitalised”, although not necessarily “democratised”, because he is unsure that consumers themselves will want or need to invest in this technology.

That may be true in Horizon’s area, where the cost of energy is heavily subsidised by the government (it guarantees the same price of power in remote areas as it does in the big cities).

That puts the onus on utilities like Horizon and Western Power, which services the main grid in the state’s south west corner, to invest in renewables, storage and distributed energy to lower the cost of service, so long as they can get a regulatory re-set that smooths the transition.

Horizon has already been down this path, replacing poles and wires with stand alone systems after fires swept through areas around the south coast town of Esperance in late 2015.

Like Western Power, Horizon has found the SAPS – based around solar and storage, with the support of diesel genesis, to be cheaper, cleaner and more reliable than the grid-based alternative, and Tudor speaks of a “huge pipeline” of opportunities in remote areas, and on the fringes of Perth.

“We are collaborating with Western Power to unlock the enormous financial, reliability, safety and emissions benefits, and it is only a matter of time till the regulatory frameworks catch-up and we see hundreds and thousands of these systems across the country,” he says.

Indeed, Western Power shares Horizon’s view of a more distributed grid. It wants to break up its centralised grid into a more modular arrangement, where some areas are off-grid completely (using micro grids), some have “thin” attachments to the main network, but are mostly self-reliant.

To address the regulatory issues (the regulator is still locked into the old hub and spoke model), Horizon says it is developing an innovative regulatory framework that supports these renewable microgrids, protects customers, and provides appropriate incentives for utilities.

Tudor says that even the bigger grids within its area will operate at higher renewables. It is currently trialling two 1MW batteries at the Mungullah Power Station in Carnarvon to slash costs.

And it is undertaking what it says is Australia’s largest remote microgrid project in the coastal town of Onslow, where it is targeting 50 per cent renewable energy with a high proportion of distributed energy resources.

Horizon says it the Onslow DER microgrid project is the first major deployment of a complete DER business model by an Australian utility.

It has also completed a demand based pricing trial with 400 customers in Port hedland, and plans to roll out the pricing model, dubbed MyPower, to other towns.

“The trial was a huge success. It showed that customers “got it”, liked it and made changes for it, (and we are) seeing some reduction in peak demand for the group as expected,” Tudor says.

The key, however, is to develop the technologies to enable this.

Up till now, most renewable investment have been “unmanaged”, and this graph illustrates the sort of technologies that will be needed to meet his goals, including voltage and frequency control, ramp rate installations, virtual power plant and storage co-ordination, and other technologies.

“Most of our towns will flip over to high distributed energy at some point or another,” Tudor says. “The landscape is changing pretty dramatically.”

And he says Horizon’s unique position as a fully integrated utility – it is the generator, network operator and retailer – makes it the ideal place for a regulatory test bed for how this will play out in larger networks. That, and the massive subsidies that support its largely fossil fuel generation now.

“The future is very much distributed and I would say that we in Western Australia, and in turn for Australia, and then in turn for the world are the real sandbox for research and development.”

The goal, he says, is to make energy boring again, in other words, to remove the controversy by ensuring that customers benefit with reduced costs from the dramatic energy transition.

“Our job is to make energy boring. It was boring in the last 100 years and it’s going through a transition point at the moment. It should be boring.”

(The quotes from Tudor in this article were taken from a speech he made at the National Energy Efficiency Conference in Melbourne two weeks ago, and in a subsequent interview with RenewEconomy at the same venue).