Western Australia is emerging as one of the most fascinating grids in the world – it has a huge proportion of rooftop solar, is fast-tracking its switch to renewables and, because it is a huge isolated grid with no links to other states or countries – has to manage all this with its own resources.

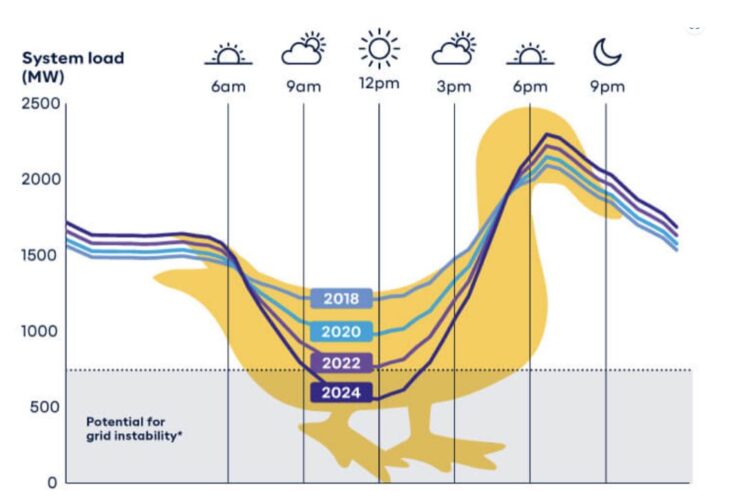

The biggest challenge is coping with the so-called solar duck, which in WA’s main grid, known as the South West Interconnected System, is reaching giant proportions (see graph below) – at least if you are a market operator trying to manage the ramp up and down of rooftop PV and its impact on the rest of the grid.

To try and control, or even squash that solar duck, the market operator and the state government this year have been busy writing first-of-their-kind contracts to three new big battery projects which are now racing to complete construction, and commissioning, before the end of next year.

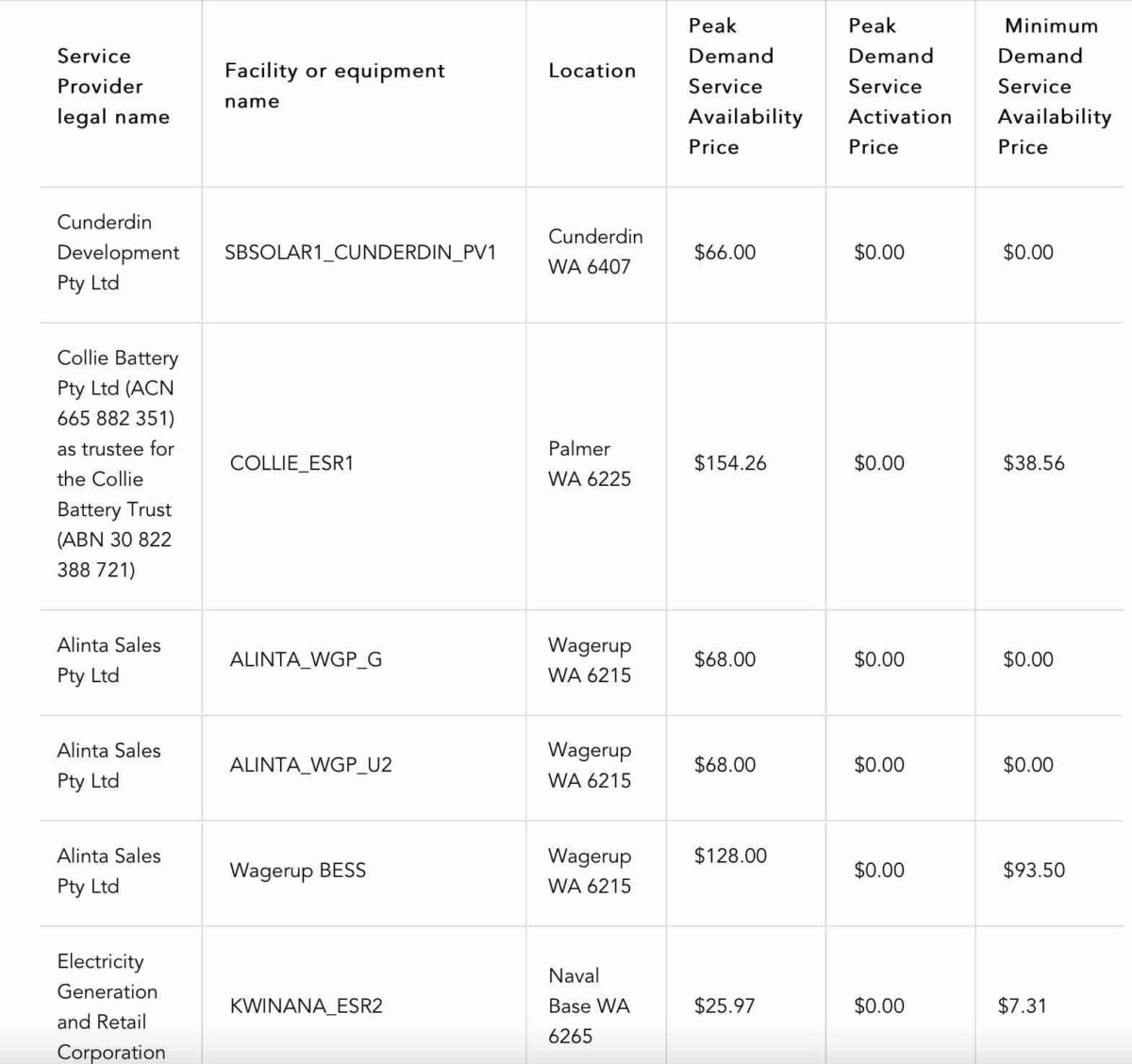

It has now been quietly revealed how much money these batteries will be paid to soak up solar in the middle of the day, and inject it back into the grid in the evening peak under the so-called Non-Co-optimised Essential System Services (NCESS) procurement process.

The program is designed to address two problems at once: the growing challenge of managing ever lower levels of minimum demand in the middle of the day – now creeping below a deemed critical threshold of 600 MW – and the need for sufficient firm capacity in the evening peaks.

But it is no small sum, even if it is for just a two year period until more firm capacity is built into the grid.

According to the data released by the Australian Energy Market Operator, French company Neoen, which has contracted 197 MW of capacity from the 219 MW/ 877 MWh Collie battery it is now building, will be handsomely rewarded.

It will get paid $38.56 a megawatt (or a total of $7,556 per half hour interval) for being available to soak up minimum demand in the middle of the day, and $154.26 per MW (or a total of $30,389 per half hour interval) for being available in the evening peak.

The payments itemised by AEMO to Neoen’s Collie battery – which will use Tesla Megapack technology – equate to around $304,000 a day.

Assuming that the contract runs on a constant basis over two years (and that is not 100 per cent clear) that translates into $111 million a year for the two-year contract, which is in line with Neoen’s dramatic lift in profit guidance announced in June when the lucrative contract was first announced.

Alinta’s 100 MW/200 MWh Wagerup battery has a different price structure for the estimated 50 MW of capacity it has entered into the scheme.

For the solar soak in the middle of the day, it has managed to negotiate a much higher payment than Neoen of $93/MW per interval, and a lower payment of $128/MW per interval for making capacity available in the evening peak.

The Kwinana battery, owned by the state-owned Synergy, is getting paid just $7.31 to soak up solar in the middle of the day, and $25.97 for being available to supply power into the evening peak – with its relatively low rates possibly being a factor of government ownership.

It continues a remarkable run of success for Neoen, which has led the field by some distance in battery storage and grid service innovation since it built the original Tesla big battery at Hornsdale in South Australia 2017.

The Collie payments are way bigger than the contracts Neoen negotiated for its Victoria Big Battery (for a system integrity scheme that supports the network) and the Hornsdale Power Reserve for a similar SIPS service (about $12 million a year and $4 million a year respectively).

It is not clear exactly how much capacity the Wagerup and Kwinana batteries have offered into the scheme, but it is assumed to be around 50MW and 150MW respectively.

Peter Kerr, from the Perth-based ATA Consulting, says the payments are good for battery storage, and reflect Neoen’s leadership in the sector.

“The payments are obviously good news for owners of operating (and near operational batteries),” Kerr told RenewEconomy. “There was always going to be a first mover advantage, but the market and regulators have been calling for improved incentives to encourage investment in storage for some time.

“We now have that, at a time when coal fired power plants are struggling to stay online and meet peak demand needs in summer. Just in time investment, you might say!”

According to the AEMO document a total of 11 projects – some including demand management packages – were contracted to provide up to 630 MW of peak demand service and 446 MW of minimum demand service.

That contrasts with the 830 MW of peak demand and 269 MW of minimum demand sought. But they got more minimum demand than asked for because of the “indivisible nature” of the submissions, which presumably refers to the fact that the batteries will both charge and discharge.

The contracts will run for just two years from October 1, 2024, to October 1, 2026, presuming the three big batteries are built and commissioned on time. Neoen has added extra capacity to its Collie battery to allow it to source other revenues, and has planning approval to expand it to up to 1GW and 4GWh of storage.

That would make it the biggest in the country, by some distance. Synergy has also flagged its own big battery at Collie, another in the south west of the grid, which could both be sized at 500 MW and 2000 MWh as the state races to install enough firm capacity to handle the planned shut down of its last coal generators before 2030.

Kate Ryan, the executive general manager of AEMO in Western Australia, says the contracts are essential to help it maintain power system security and reliability.

“However, AEMO continues to call for the urgent investment in generation, storage and transmission in the SWIS as we transition to a cleaner and more sustainable energy future,” she said in a statement to RenewEconomy.

“NCESS are procured through a competitive tender process, and are also subject to an overall cost benefit assessment to ensure they are in the overall interests of consumers.”