The screenshots in the tweet below, published last month, brilliantly illustrate both the best and the worst of current climate science.

In 2020, the @metoffice produced a hypothetical weather forecast for 23 July 2050 based on UK climate projections.

Today, the forecast for Tuesday is shockingly almost identical for large parts of the country. pic.twitter.com/U5hQhZwoTi

— Dr Simon Lee (@SimonLeeWx) July 15, 2022

The best, because what was predicted has come true. The worst, because it happened nearly three decades ahead of schedule. Oops!

Perhaps we are placing too much faith in the predictions of the climate science community. Even as climate models become more rigorous and detailed, we may be falling into the trap of turning science into scientism, “an exaggerated trust in the efficacy of the methods of natural science…”

We assume that if we change one variable (eg, CO2 emissions), it is likely to lead to a relatively predictable response in respect of another variable (eg, atmospheric temperature at a certain future date).

Thus, hundreds of climate scientists are beavering away on their laptops and mainframes around the world on ever more sophisticated and granular models of the planet’s future climate scenarios and potential impacts.

There are three problems with this colossal and laudable effort.

First, as any climate scientist can tell you, there are several factors that can subvert the idea of a predictable future—beyond the fact that any model has a margin of error, which naturally increases over the timespan of the projection.

For starters, there are compound events: when, say, drought and wind storms combine to produce much more damage from falling trees than would have been the case with only one of these impacts. Compound events are much harder to predict than those with single causes.

Another is feedback loops: the way that, say, the loss of arctic sea ice from summer melting is leading to lower sea surface albedo, thus increasing the warming of Arctic waters, thereby in turn accelerating the melting of sea ice.

Finally, let’s not forget tipping points: the fact that some climate impacts, once triggered, are irreversible (eg, the melting of the Greenland or West Antarctic ice sheets, or the release of methane from previously frozen tundra and vents in the ocean floor).

Together, these factors or processes mean that, having already warmed the atmosphere by over one degree and with more warming locked in due to the lag effect (even if we stopped burning fossil fuels today), the future climate is to a large degree unknowable.

This conclusion is borne out even in the IPCC’s periodic assessment reports, which are careful to spell out the limitations of the models. For the most part, they therefore do not take these factors into account—essentially because to do so would make the modelling task too difficult and uncertain.

This brings us to the second reason for scepticism.

When we hear climate scientists, politicians and environmentalists say things like “We need to cut emissions by X percent by 2030 to keep global warming to 1.5°” (or Y percent by 2050 to keep warming to 2°—the actual numbers are not important here), what degree of certainty do you imagine they are assuming? Depending on how you interpret the IPCC reports, as far as I can tell their level of confidence in the mitigation models is either one in two or two in three.

In other words, there is either a 50% chance or perhaps even a 67% chance that they may be wrong – either too conservative or too radical.

This is horrific. If I was standing on the edge of a busy road, and I asked the nearest statistician what the chances were of safety reaching the other side if I try to walk across it, how confident would I need to be in order to take the first step? Personally, I’d want at least 90%, and preferably 99% plus.

Translated to climate science, if we wanted a higher degree of confidence than two in three in the projections about the action required to keep global heating to no more than 1.5°, we would need to take much stronger action today than even the most radical mitigation plans suggest. Delaying emission reduction means we are playing Russian Roulette with the climate and our future.

So to the third and final reason to be sceptical about climate modelling. It just doesn’t square up with our recent lived experience. Around the world, we are already experiencing extreme weather events – wildfires, floods, droughts and storms – and biodiversity loss consistent with or exceeding the upper bounds of IPCC projections.

The tweet above is a stark illustration of this new reality. The recent heatwave affecting the UK, Ireland and much of Europe is consistent with the UK Met Office’s projections for 2050—that is, one human generation early.

In Australia, it would be a brave climate scientist who would interpret the last three years of drought, followed by bushfires, floods and storms, as an aberration rather than being either part of a long-term trend or indicative of a step change in climate impacts.

The climate science community tends to be conservative in its projections in order not to fuel the fires of denialists, who pounce on uncertainties to argue that while the science is unsettled, we should not act to reduce emissions. But in so doing, scientists may unwittingly have lulled us into a false sense of security, as if tweaks to current policy settings can help us to avoid a chaotic future.

In reality, the future is here. And we are obviously unprepared.

So, what to do?

First, stop pretending that there is still time. Climate change is already catastrophic, and it will get worse. That doesn’t mean we should give up, though, because every action to reduce emissions, however seemingly infinitesimal, will help to limit the severity of future damage.

Second, stop imagining that the past is a reliable guide to the future. The classic example is the use of probabilities in taking adaptive action. When a supposed 1 in 100 year flood happens, we can’t assume the next one will be a century away. It could be a year, even a month away, as it was on the NSW North Coast and in Western Sydney earlier this year.

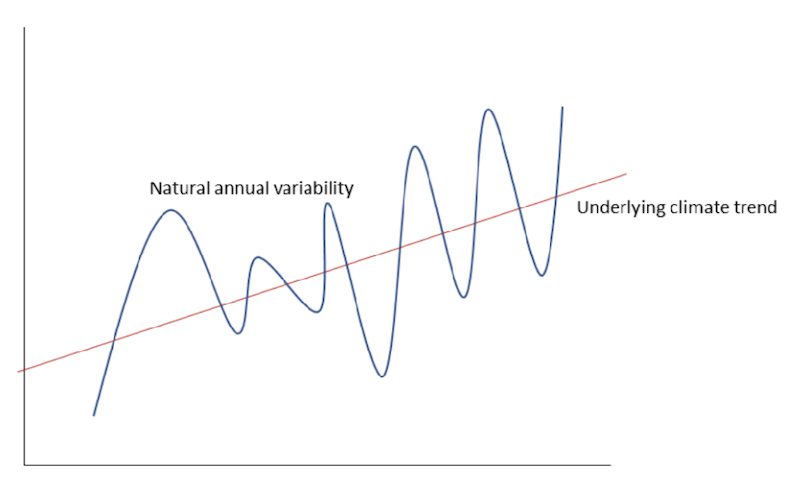

Third, be sceptical of projections out to 2100 and graphs of linear timelines. As in the graphic below, change is likely to involve considerable short-term “static” (ups and downs) that are usually hidden in long range projections, as well as step changes that may arise without warning. Encourage climate scientists to talk about the uncertainties in their models as reasons to act now, rather than to defer action.

One of the other key lessons from the modelling that is beyond debate is that we can still shape the future, especially if we are able to “draw down” emissions already in the atmosphere. So, as ever, hope for the best, plan for the worst – and don’t give up.

Mark Byrne is Energy Market Advocate at the Total Environment Centre. Thanks to Dr Jill Cainey for the graphic.