Elon Musk has managed to get people to drool over an environmentally friendly electric vehicle. But it is neither the good looks nor fantastic acceleration – but rather the automation of his cars – that will lead us to abandon oil-thirsty cars.

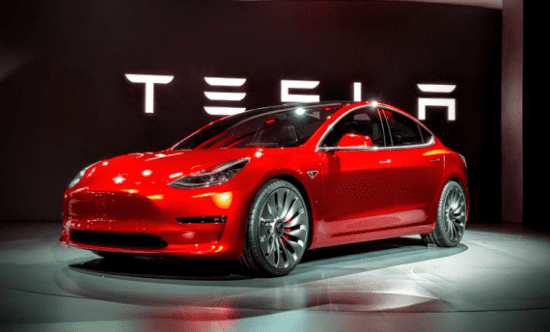

The unveiling of Tesla’s car targeted at the masses, the Model 3, evoked plenty of admiring oohs and ahhs over its good looks and incredibly rapid acceleration.

Yet the real fundamental breakthrough in encouraging us to abandon oil-thirsty vehicles was barely commented on. Elon Musk announced that even though the car would cost less than half that of its flagship Model S, it would incorporate the ‘autopilot’ feature, that allows the car to drive itself, not as an optional extra but as standard.

The technology that enables this car to drive itself may seem exotic, but just like other safety features, such as anti-skid braking and stability control, it will rapidly filter down to more affordable cars (to see Tesla’s Model S drive itself down one of Melbourne’s busiest roads – the Westgate Freeway check out this video or see these clowns play pattercake while the Tesla drives itself around a semi trailer in this video).

Car afficianados and transport experts are already well aware of this, and planning for the advent of cars and trucks that drive themselves pretty much on any formed road you might want to go.

But what is yet to receive widespread attention is how fully automated cars, when matched with mobile apps like Uber, are likely to lead to a major breakthrough in lowering carbon emissions.

How is this possible?

The reason boils down a superb triumph of convenience and lower cost, over car manufacturers’ extraordinary past success in manipulating our emotions to buy bigger and more powerful cars, at the expense of fuel efficiency and our wallets.

To help explain I need to give you a quick personal history lesson.

What is holding us back from reducing emissions – not technology but emotion

Presumably as punishment for horrible sins in a past life, back in 2002 I was hired into the Sustainable Transport Team within the Australian Howard Government’s Greenhouse Office. We were supposedly tasked with finding ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from transport. But in reality we weren’t allowed to do the only thing that we knew would make a meaningful difference– introduce regulatory standards to mandate improvements in vehicle fuel efficiency.

The reason why we’d come to realise you needed mandates is because it is not a lack of affordable technologies that was holding us back from reducing vehicle emissions. The problem boiled down to:

- no matter what fantastic technological innovation was dreamt up within the engineering departments of car companies to improve engine and drivetrain efficiency;

- their marketing department would piss the fuel (and emission) savings up against the wall converting these innovations into cars that went far faster or were far bigger than anything we would have ever thought we needed just a handful of years previously.

That chart below helps illustrate my point in hard quantitative numbers. The data is for the US passenger vehicle fleet, but similar trends have occurred in Australia as well. Fuel economy (shown in the blue line) experienced a rapid improvement in the 1970’s spurred in part by skyrocketing fuel prices but critically also new fuel efficiency regulations. Then over the 1980’s to mid 2000’s fuel efficiency of the overall passenger vehicle fleet slowly but steadily got worse.

US average new passenger vehicle fuel economy (miles per gallon), power and weight over time

One hundred years on from 1908 when Henry Ford made motor vehicles a mass consumer item in the US with his Model T, the average fuel economy (and therefore carbon emissions) of the American vehicle fleet had barely improved. In fact, the best-selling car in the US back in 2008 – the F150 pick-up truck – had worse fuel consumption than the Model T.

But this wasn’t for want of technological improvements in the efficiency of motor vehicle engines and transmissions. As the chart above illustrates, while fuel economy slowly got worse between the 1980’s to mid 2000’s the power of cars absolutely skyrocketed (fuel economy has since improved significantly but this is in large part down to upgraded fuel efficiency regulatory standards).

At the same time an increasing proportion of consumers decided a standard passenger car no longer cut it. Instead they needed a four wheel drive or SUV capable of taking their family, and their caravan, off into the wilderness. This led to an increase in the average weight of cars.

The Australian Bureau of Transport and Regional Economics estimated back in 2003 that over the prior 20 years while vehicle fuel economy stalled, the average fuel consumption of vehicle engines per unit of maximum power output had decreased by around 45 per cent.

In other words, if cars’ weight and power were kept constant then we would have achieved almost a halving in vehicle fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions per vehicle kilometre travelled.

That’s a massive technological advancement, but instead greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles in Australia and the US rose considerably.

For the most part we struggle to take advantage of these advancements in vehicle power and off-road ability. Speed cameras have proliferated to enforce speed limits, while traffic congestion means that the average car trip in our cities is about 35 to 50km/h. In addition it is well acknowledged by car companies that most buyers of SUVs would rarely take the car off a bitumen road.

You see, car marketing departments worked out long ago that Henry Ford had it all wrong. You don’t make particularly good profits by producing cars that play to some rational evaluation of practicality and cost. No, you make good money by playing to our emotions.

How the automated car divorces us from an emotional attachment to our cars

But the arrival of the automated car, when coupled with a smart phone completely undermines this clever marketing ploy. It opens-up the possibility of vastly reducing the number of cars that we need, saving us large amounts of money, while at the same time radically reducing the fuel consumption of cars. Indeed it will help rid us of petrol-burning cars altogether.

This is a function of the fact that once cars become automated two things happen which are now well recognised by tech companies, stock analysts and the auto-makers themselves.

- The end of car ownership

Firstly, why own your own individual car when you can call one up at a moment’s notice which will cost vastly less than owning your own car while being no less convenient?

The reality is that cars are expensive. Yet for most of us, the car sits around doing not much other than depreciate for 22 out of 24 hours in the day. Automated cars can drop you off at work and then be easily redeployed to transport someone or something else (look out couriers) rather than sitting in a car park. This offers up room for vast savings by reducing the number of cars we need without sacrificing convenience.

- Rightsizing cars to suit individual trips not lifelong dreams

Secondly, if you no longer drive the car you’re in, and you no longer own it, do you really care about the performance of the car or whether it matches your image as an adventurous outdoorsman?

For the most part cars are incredibly over-specified to fulfil their most regular functions. Australian city dwellers for most the year would use their car to travel less than 30 kilometres in a day at an average speed of around 35-50km/h, usually carrying just one person and little luggage. Yet these cars are almost always built to be capable of travelling substantially above the national speed limit of 110km/h for several hundred kilometres between refuelling while carrying five people and a fair bit of luggage as well. Sometimes we need this functionality, but most of the time we don’t. And this excess functionality comes at significant cost.

Now imagine if we move to a model of hiring cars by the trip rather than owning them outright – a business model tech giants Google and Apple as well as General Motors are already developing. Using an Uber-style app, we’ll punch in the trip we want to undertake and the number of passengers and any unusual luggage requirements. The hire car company can then right-size the car to match requirements for that specific trip. So instead of getting a car that’s built for that one time each year you take the entire family and a caravan off-road camping (or perhaps only just dream about it), it might instead be suited to simply transporting say two people 10 kilometres across town at a speed lucky to exceed 80km/h.

Hire car companies have a very strong incentive to downsize vehicles because smaller, less powerful cars are vastly cheaper to purchase and fuel. A small Mitsubishi Mirage costs $15,000 and consumes 4.9 litres of petrol per 100 kilometres of travel. By comparison one of the best selling cars in Australia – the Toyota Hilux Dual-Cab costs $46,000 and consumes 7.6 litres of diesel (in a lab test but a lot more in real life), while a slightly smaller Toyota Camry costs $27,000 and consumes 7.8 litres of petrol. Multiply that over several thousand vehicles and it represents an incredible amount of money a hire company could save through rightsizing.

How automation overcomes electric vehicles’ greatest weakness

Ultimately though rightsizing will facilitate the step to cars that don’t consume any petrol at all.

The Achilles heel of electric vehicles is that batteries cost a lot of money per kilometre of driving range. Otherwise electric vehicles are superior to a conventional car in every other respect. Electric motors are cheaper, simpler, more efficient and provide better durability than an engine that explodes fuel several thousand times per minute.

But batteries’ driving range shouldn’t be that big an Achilles heel once you consider that the vast majority of car trips don’t actually go more than 20km. Once cars are hired out by the trip, rather than owned outright, the driving range of a car between refuelling becomes far less relevant. For those rare occasions when you need to take a long trip then the hire company can send you a petrol-fuelled car capable of travelling 500 kilometres or more on a tank. Otherwise an electric vehicle with 150 kilometres of range between refuelling should still manage to do multiple trips between a 30 minute recharge. Within the decade such an electric vehicle will probably cost about the same as a conventional small car, while being more reliable and less costly to operate and maintain.

The automation of driving offers to relieve us of one of our most annoying tasks – dealing with congested traffic. But it offers something far more profound – a circuit breaker between our ego and our means of transport. In doing so it could facilitate huge reductions in vehicle carbon emissions and ultimately the proliferation of vehicles with no tailpipe carbon emissions at all.

Tristan Edis is the Director – Analysis & Advisory at Green Energy Markets, a firm that helps its clients make informed decisions about renewable energy, energy efficiency and carbon abatement markets. He was the former editor of Climate Spectator.