We react to disaster compressed in timescale, in proportion. This is why COVID19 spurs emergency action but the slow-burn of fossil-fuel caused climate change doesn’t quite manage the same (among other things). It’s also partly why the spectre of nuclear meltdown is so salient. That sensation – of the fear of a sudden, inescapable catastrophe – is universal. The immobilising feeling of a health and safety risk you cannot escape, but that you never asked for and that you don’t benefit from is the root cause of plenty of sub-types of technological backlash, from Wi-Fi, to 5G to wind turbine syndrome.

In fact, the very first piece I wrote for RenewEconomy, in 2012, was about backlash to technology on the grounds of safety and health. “Significantly, individuals will come to harm as they experience needless anxiety as the direct result of unscientific health claims. The onus is on the wind industry, and the media, to present clear and relatable information”, I wrote. I was employed by wind farm company Infigen Energy at the time, in the company’s operations centre.

Health fears around wind farms emerged in Australia roughly around the same time as a combined earthquake and tsunami struck Japan. On the 11th of March 2011, this disaster disabled the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, located on Japan’s east cost. Several thousand residents were evacuated. Hydrogen explosions occurred in the reactors, blowing off the roof and resulting in the spread of radioactive fission products into the atmosphere.

Why couldn’t the power plant withstand the tsunami? The official Japanese government inquiry found that it was “collusion between the government, the regulators and TEPCO, and the lack of governance by said parties. They effectively betrayed the nation’s right to be safe from nuclear accidents”.

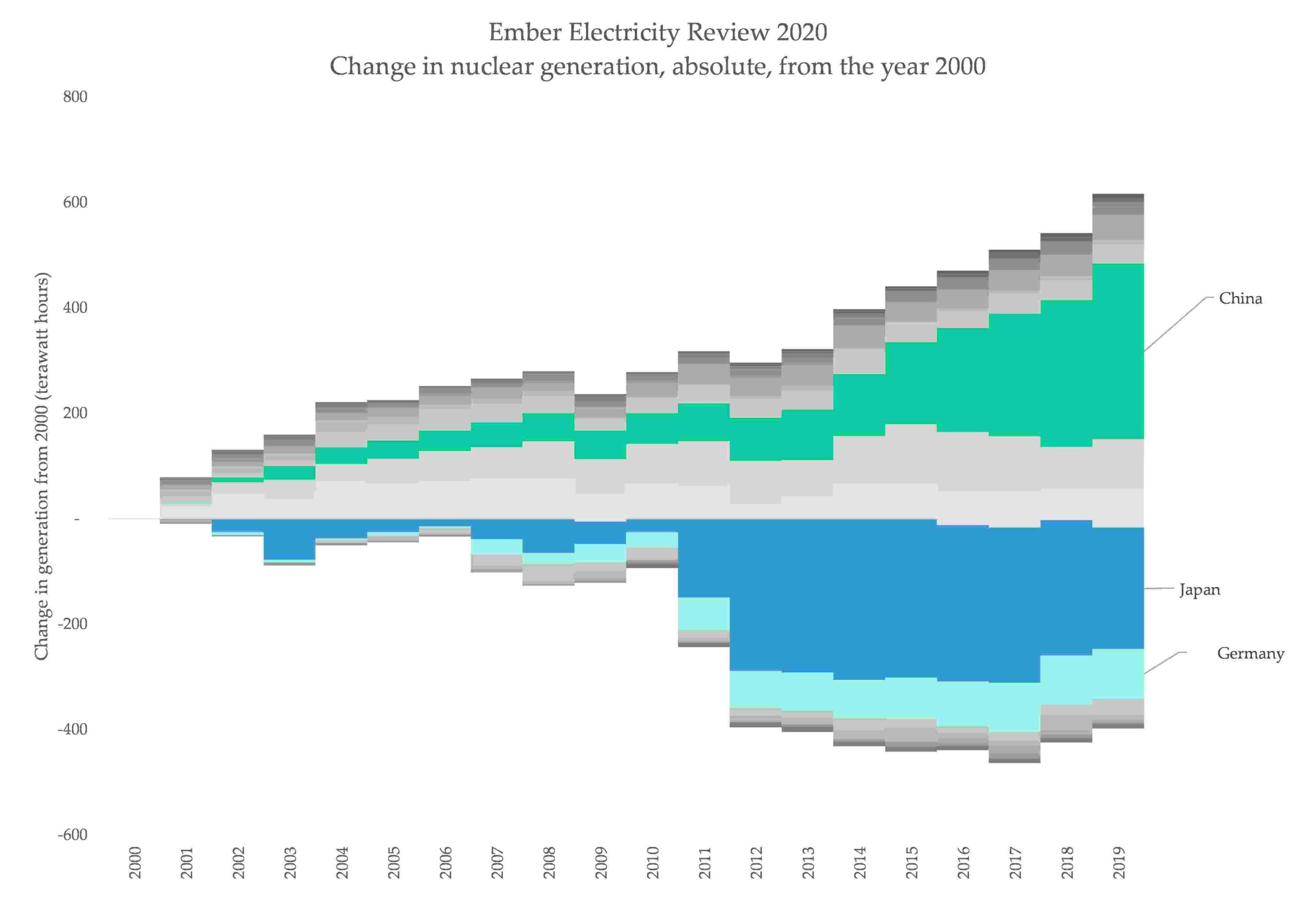

The impact of the accident was unmissable. Japan’s fleet of nuclear power stations were shuttered almost immediately. The most noticeable flow-on impact was Germany bringing forward its planned nuclear phase out from 2036 to 2011. However, these shutdowns levelled off only a few years later, and the reduced output from these decisions has been entirely cancelled out by rising nuclear output in China, as shown in Ember’s 2020 electricity review:

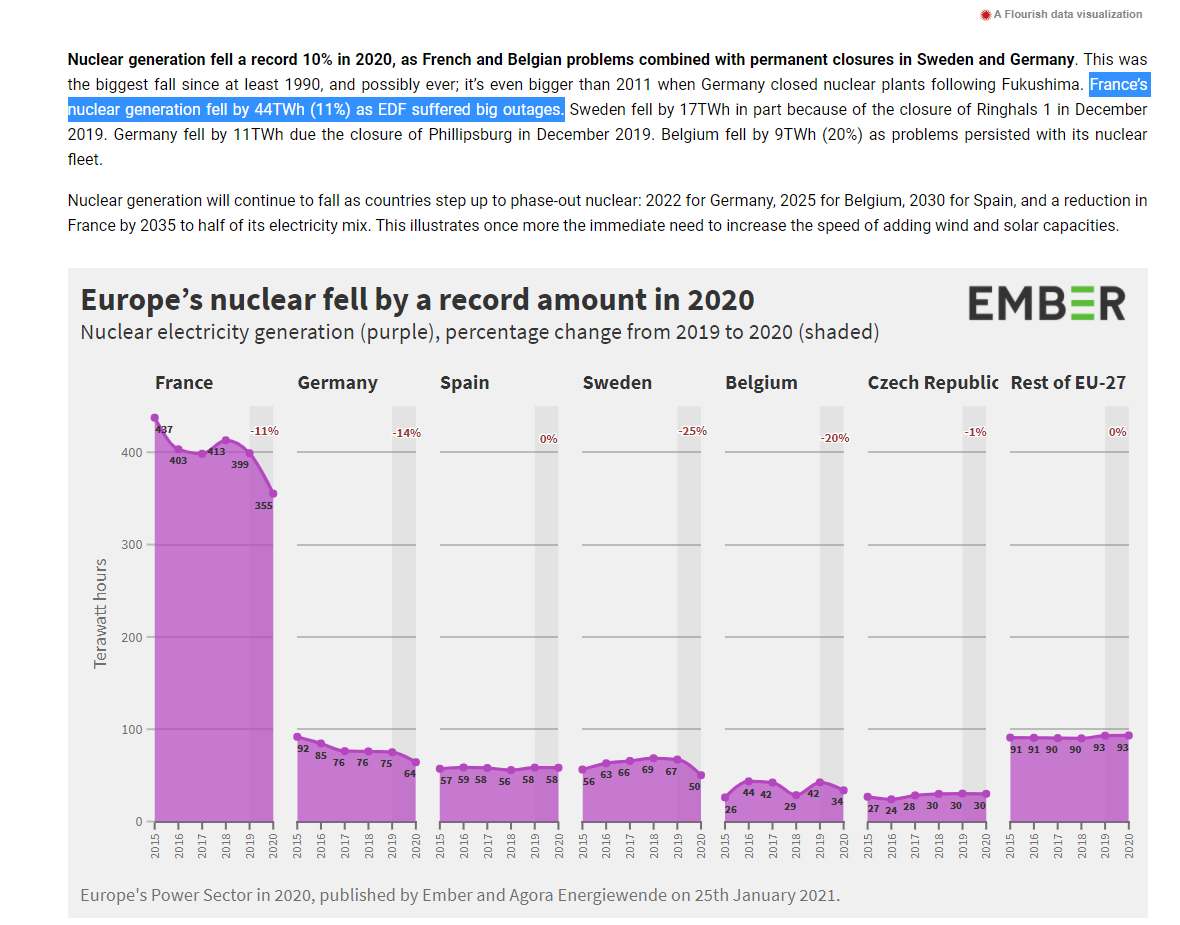

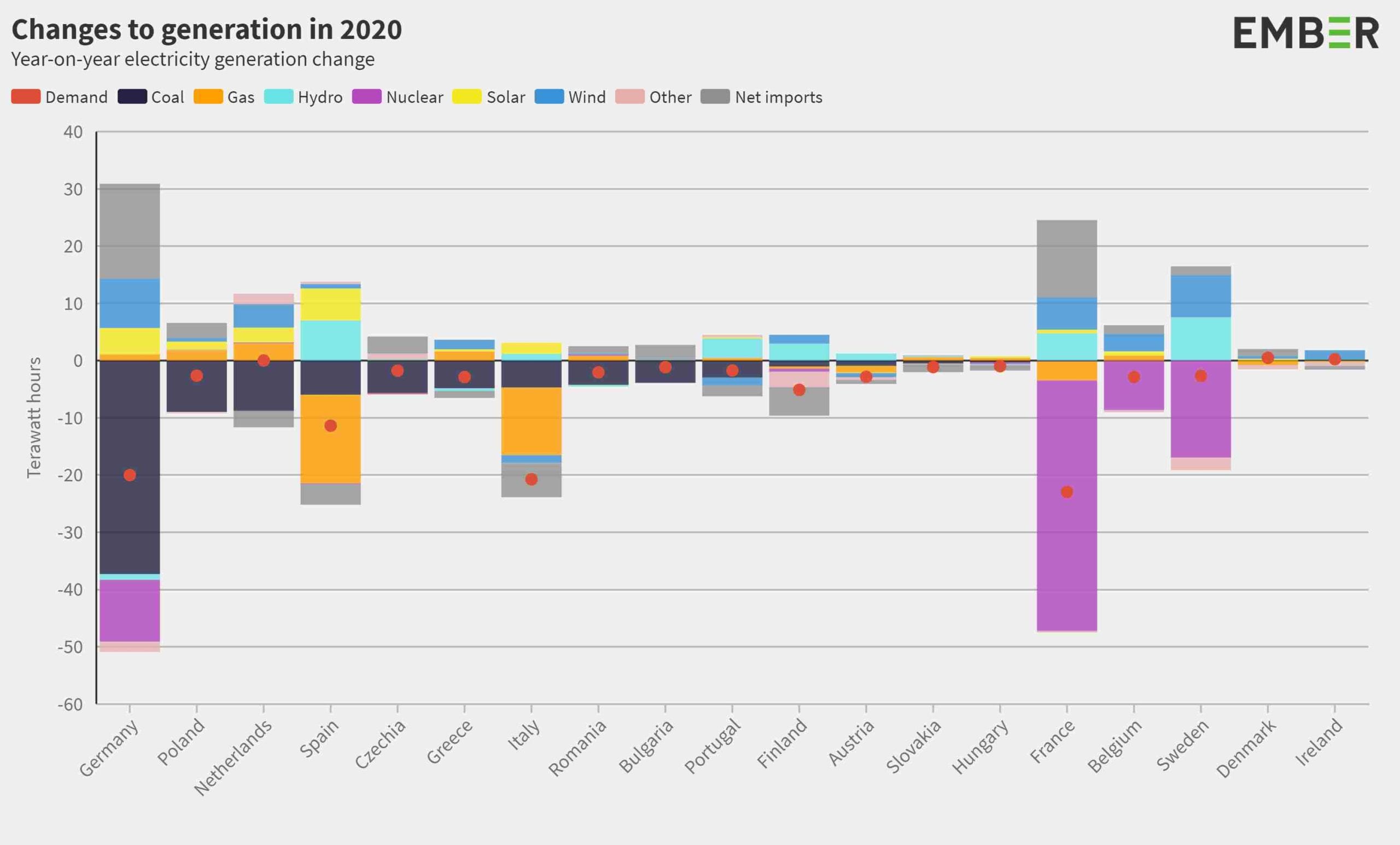

A more recent report from Ember focused on Europe highlights the magnitude of change in Europe, and in particular, in France, often heralded as the flagship country for nuclear power deployment, and utterly unavoidable in debates or discussions about nuclear.

A more recent report from Ember focused on Europe highlights the magnitude of change in Europe, and in particular, in France, often heralded as the flagship country for nuclear power deployment, and utterly unavoidable in debates or discussions about nuclear.

What that report shows is that in 2020, nuclear power suffered its most significant fall in output probably on record – notably, even greater in scale than the drop after Fukushima. Belgium and Sweden too have seen significant drops in nuclear power.

In an alternative universe where the political and cultural factors never led to the Fukushima nuclear accident, it’s tough to imagine a global electricity system all that different from today’s. Wind and solar would likely still be on a steep downwards cost curve, fossil fuels would still be raking in subsidies (sometimes with the support of the nuclear industry), and though nuclear’s output would still be higher, it would still certainly face the deeper, longer-term economic issues that have defined its growth and decline over the past several decades.

“The history of nuclear power is something of a rollercoaster from inflated claims and optimism to disillusionment,” said Dr Simon Taylor, of Cambridge Judge Business School, to mark the ten year anniversary of the accident. The only advanced economies looking to build nuclear power are the UK, and Finland. “But the main reason is not a shift in public opinion following Fukushima, with attitudes remaining surprisingly favourable in the UK. The problem with new nuclear remains economic: it costs too much to build,” said Taylor, author of the book The Fall and Rise of Nuclear Power in the UK: a history.

In Australia, nuclear power remains illegal, under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Act. It has sat around the middle of popularity surveys for some time, but has seen an extremely gradual softening in public perception over the years. Politically, it’s only ever mentioned as a tactic for conservative politicians to provoke their foes, and is championed mostly by those who also aggressively oppose climate policies, including those that would be needed to make nuclear economical in Australia, such as carbon pricing.

The Fukushima accident has been at times framed as a turn-around point – a disaster exploited by cynical Greens. It was exploited at times, but at most it accelerated pre-existing trends.

In some places in the world, it seems important to sweat nuclear plants for as long as possible. In the US, for instance, the boom of cheap fossil fuels and an absence of strong renewable policies mean gaps will be filled by higher-polluting plants. In Europe, the drumbeat of closures is essentially inevitable, and that means deploying replacement clean energy portfolios as quickly as possible to ensure fossil fuels don’t take hold.

The Fukushima disaster simply catalysed a collection of deep, systemic factors that were already in place, and remain in place today. Nuclear will certainly play some role in the world’s future electricity grids, most likely in countries like China and India. But elsewhere, it is wind and solar that have become the most favoured to serve as the workhorses of grids. They too are not immune to public backlash, to poor economics or to industry headwinds, and there must be far more effort put in to ensuring they don’t suffer a similar fate.