The Northern Territory government has unveiled plans for a massive renewable hydrogen zone, as well as a new rewewable energy hub, as it seeks to grab a major share of Australia’s renewable hydrogen export opportunities and transition its local electricity networks.

The plans are laid out in three key documents released this week that are focused on what’s needed to deliver on its promise to reach 50 per cent renewables by 2030, and to grow a multi-billion dollar market in renewable hydrogen that it hopes will replicate its success in LNG.

The documents make clear that the NT has some of the best solar resources in the world, particularly in the southern part of the territory. “Sunshine for sale”, it boasts.

This has been long recognised, but the NT’s efforts to reach 50 per cent renewables – first announced in 2017 – have been stalled by divisions over grid design and market rules, and how to accommodate new technologies into ageing networks, and controversies over a series of blackouts.

So far more than 45MW of large-scale solar has been built, but not connected because the local regulators are scared of what might happen when they do. Some of the solar farms have been sitting idle for nearly two years, and legal action is being threatened over new rules.

The new document is recommending a three-stage process to facilitate the transition, and recognises that a lot of battery storage will be needed to accommodate solar, particularly as no significant wind resource has been identified.

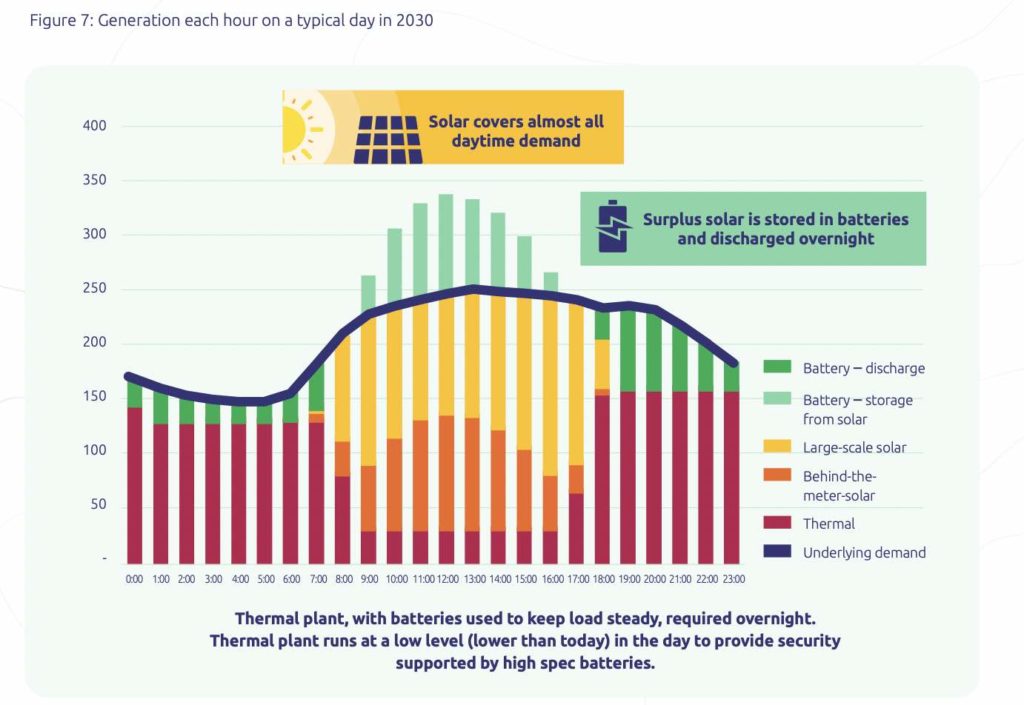

It now envisages an energy mix of 50 per cent renewables by 2030 coming from small-scale solar (15 per cent), large-scale solar (26 per cent), with battery storage (9 per cent), which will provide overnight storage and critical grid services.

The remaining 50% of electricity generation will come from more efficient and agile thermal energy, replacing the existing less flexible plant, and including equipment that can be fuelled by renewable hydrogen.

This is what it imagines an average day to look like in 2030.

It is looking at 320MW of solar – 80MW from rooftops, 60MW committed large scale solar, and another 180MW of large scale solar from a new renewable energy hub.

There will also be a need for more big battery storage – a total of 110MW. Homes and businesses will provide 10MW/40MWh, with utility-scale batteries providing another 100MW/560MWh; so it is planning batteries with up to six hours storage.

A further 100MW of “hi spec” batteries (and presumably short-term storage) will be needed for grid security. Virtual power plants and demand management will also play a role.

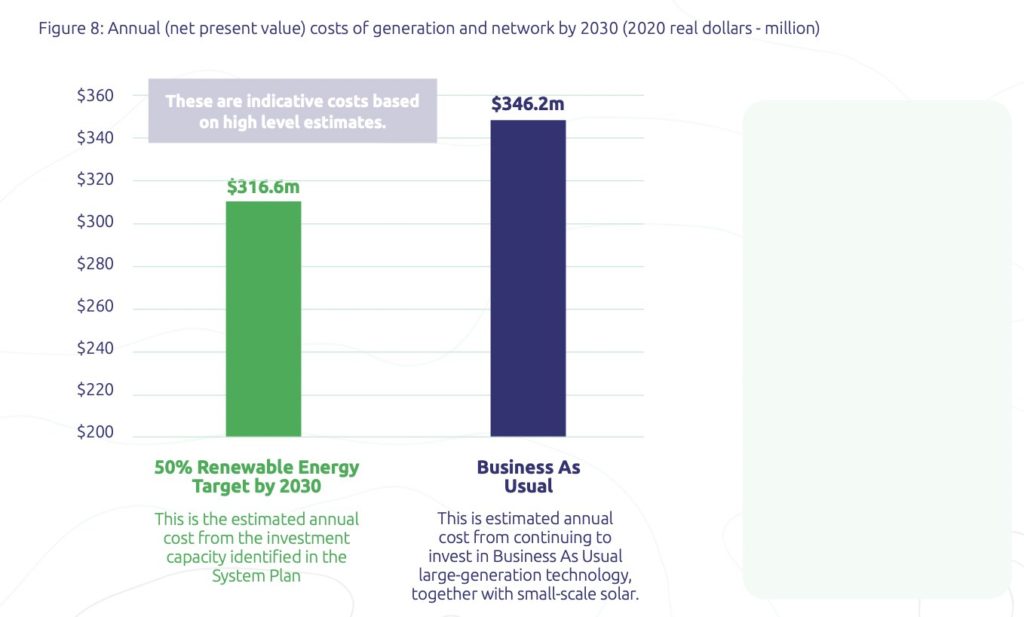

The rollout is expected to be steady over the next eight years, but the government says the good news is that it will result in cheaper electricity costs. It estimates savings of around $30 million per annum, compared to following a Business As Usual scenario, where ageing gas plants were replaced with the same technology.

But it hopes that the gas plants will not be burning fossil fuels over the long term, and will instead turn to renewable hydrogen, fuelled by vast arrays of solar panels – and possibly wind farms if the resource can be firmed up – from the southern part of the territory.

Sun Cable has already planned a massive solar farm of up to 20GW, and more than 40GWh of battery storage in the NT, primarily to provide cheap solar power to Singapore, but also to support low-carbon manufacturing and industries in the NT with cheap power.

It remains to be seen what role that massive project will play in the NT’s own hydrogen plans, and its mission to reach 50 per cent renewables in the grid (given its sheer scale will be more than 20 times the needed capacity of the local network).

The NT government recognises the long-term storage potential of renewable hydrogen and is looking at creating a “renewable hydrogen zone” that would stretch from around Tennant Creek down towards Alice Springs.

“Renewable hydrogen could be produced in arid regions of the Territory using either water capture technology, such as that being developed by Aqua Aerem, or utilising ground water resources where available,” it says

“While hydrogen production is water-intensive, even export-scale production utilisation is comparable with other existing industrial water allocations.