The Northern Territory is a tough place to do renewables.

Yes, Australia’s two richest men Andrew Forrest and Mike Cannon-Brookes duelled over the rights to build what could be the world’s biggest solar farm, but the reality is that three smaller facilities in the Darwin grid have been sitting idle for several years, cut out of the market by zealous rules made by cautious regulators.

Further south, in Alice Springs, the transition to renewables has been no less painful. It boasted, in 2012, what was briefly the biggest ground mounted solar facility in the southern hemisphere – all of 3.8 MW at Uterne – and the first solar facility in Australia to strike a price from a reverse tender.

Since then, not so much has happened. One quarter of homes have installed rooftop solar, but the grid operators have struggled to manage the deepening solar duck curve, and when a lengthy blackout hit the town in late 2022 there was hell to pay in media headlines, and the two most senior executives in the territory lost their jobs.

But some people cared deeply about the town and its green energy transition, and whether it can actually meet the territory’s 50 per cent renewable target by 2030, a target that seems low compared to what is happening in the rest of the country, but is made difficult by the near zero prospect of competitive wind.

The Alice Springs Future Grid, a detailed analysis of the options to reach 50 per cent renewables, and how to build the systems to get there, is a remarkable collaboration of energy experts, community advocates, government officials, energy workers, regulators, policy makers and the biggest utilities in the region.

It has delivered a collection of scenarios that, given the context and history of the NT’s renewable roll-out, seems pretty stunning. One of them suggests running the town solely on solar and battery storage for up to five hours a day, every day. Another scenario suggest 1.5 hours of 100 per cent solar, per day.

Even more remarkably, the two scenarios have been agreed – both by the owners of the fossil fuel gas and diesel generators, and by those responsible for keeping the lights on – as entirely plausible.

Such scenarios now seem everyday for other isolated grids, particularly mine sites. But these are facilities that are controlled by a single owner – the challenge with Alice Springs, as we reported earlier this week – is negotiating through a maze of regulatory layers, and utilities, and managing the needs of the 26,500 people that live there.

“We’re imagining a world where for up to 20% of the year, for five hours a day, you’re turning the engines off in one of our scenarios, and we’re all looked at it and gone, ‘yeah, that’s plausible’,” Frearson tells Renew Economy in an interview in the latest episode of its popular and weekly Energy Insiders podcast.

“10 years ago, if I’d suggested that, I would have been put into an institution of some form, people would just not have considered that as being a viable way of thinking about our system.

“To have been part of a project team that included the owner of those generators, and included the system controller …. and the network operator. To have all them sitting in the right room going well, it wouldn’t be easy, but if we did it, it would have to look like this.

“And then to be able to produce a report where two out of the four scenarios …. agreed by all the parties as being plausible scenarios – to contemplate a world where we have zero fossil fuel generation – that’s actually pretty remarkable.”

So, what do those scenarios look like?

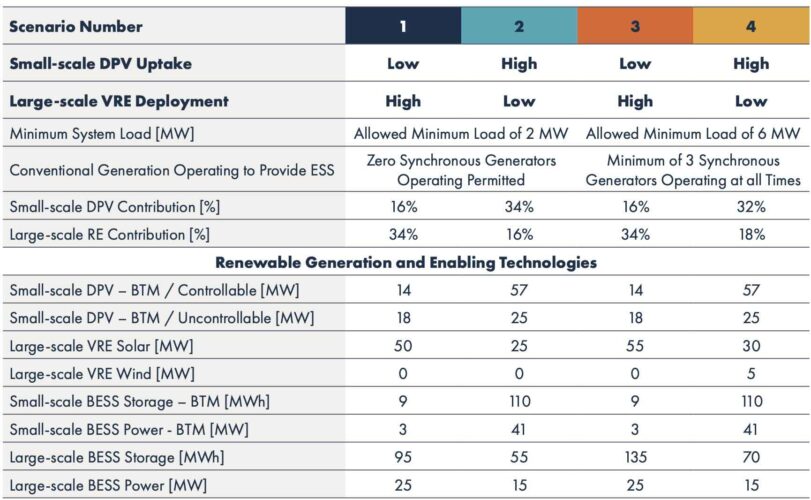

The two options differ from the amount of rooftop and utility scale solar, and the amount of behind the meter and utility scale storage.

In the behind the meter scenario, small scale solar makes up 34 per cent (or two thirds of the 2030 50 per cent renewables target), with 57 MW of “controllable” and another 25 MW of legacy “uncontrollable” solar. There would be 25 MW of large scale solar.

Small scale batteries make up the bulk of storage, with a total of 41 MW and 110 MWh, with 15 MW and 55 MWh of large scale storage.

The alternative is to double the size of large scale solar to 50 MW, and limit the amount of small scale solar PV to 18 MW uncontrollable and 14 MW controllable. Large scale battery storage will double to 25 MW and 95 MWh, and small scale batters will be just 3 MW and 9 MWh.

The advantage of these scenarios is that they allow maximum flexibility, with minimum load allowed to fall to just 2 MW as a result of the solar duck curve, with the batteries keeping the grid together in the absence of any gas or diesel generators.

The small scale scenario would allows for 517 hours a year of “fossil fuel off”, while the large scale variant allows 1555 hours a year of no fossil fuels, or an average of nearly five hours a day.

The other scenarios contemplate a future where at least three fossil fuel generators continue running at all times. But the big change is the need for significantly more large scale storage because it will need to soak up more solar during the day.

This is one of the issues of dealing with a grid dominated by solar, which will include Australia’s main grid – the National Electricity Market.

If the operator insists on keeping “base-load” or fossil fuel generators running even when there is enough renewable output to meet demand, more storage is required. It’s an added cost which the proponents of nuclear power in Australia, for instance, have yet to address. It may not even have occurred to them.

Back in Alice Spring, Frearson says whichever of the options are formally adopted, the regulators and policy makers now have a clear path to ensure that all the “systems” are in place to facilitate those scenarios.

“When we started the report we were doing exactly the same thing that everyone else does, which is, well, what’s 2030 gonna look like?” Frearson says. “But you just end up in an argument about what the future may be.”

Hence the multiple scenarios. “As we looked at each of those solutions, and said, well, starting with the end in mind, working back to where we are now, what are all the things you’ve got to do to get there.

“And what you see is actually, they all come to start to share very common sets of activities that need to occur over the next two to three years in particular.”

You can listen to the full interview with Lyndon Frearson on the latest episode of the Energy Insiders podcast here.