A 200MW Victorian solar farm and battery storage proposal that has been engaged in a landmark battle over land use in Camperdown, in the state’s south west, has lodged a revised planning application with the state government.

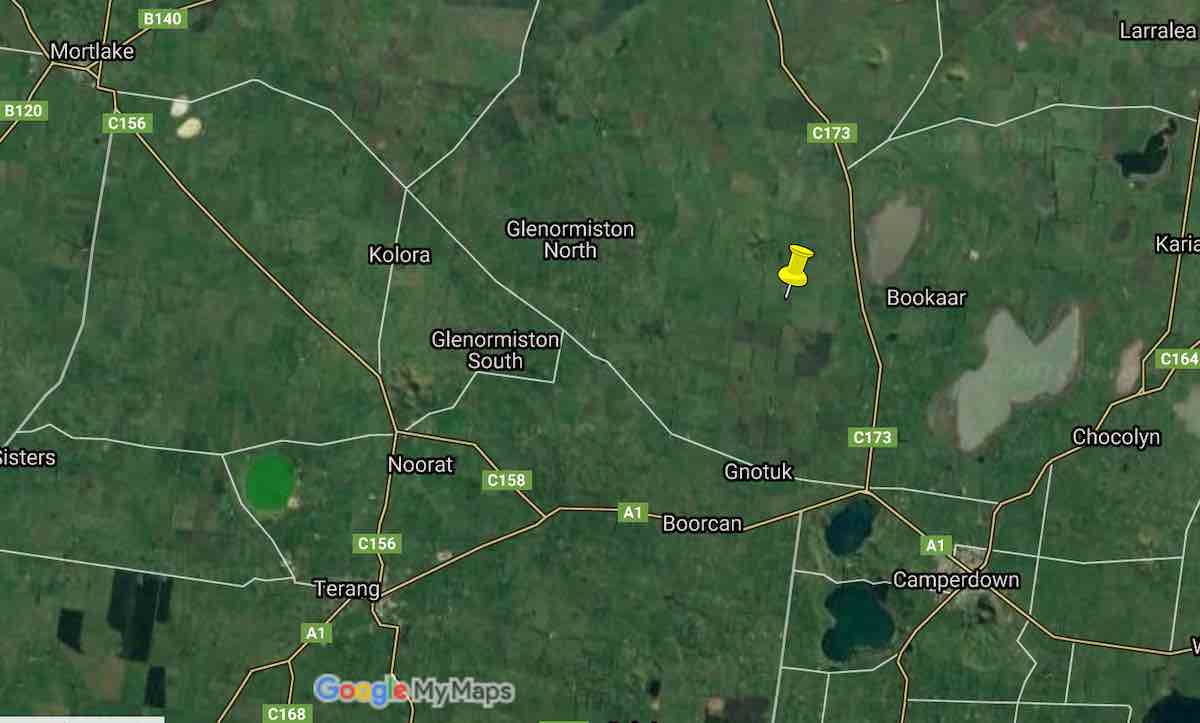

The Bookaar solar farm – a joint project of Infinergy Pacific and the McArthur family who own the land slated for the development – proposes to install 700,000 PV panels, inverters, a substation and battery storage on farm land just outside of the town of the same name.

The project was rejected by the Corangamite Shire council in 2018, based on a range of concerns including visual impact and loss of agricultural land. It was then sent back to the drawing board in August of 2019 after an appeal to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal failed to overturn the council’s decision.

As RenewEconomy reported at the time, the Tribunal came to a similar conclusion to the Council, pointing to “deficiencies” in the project’s planning application, particularly around flooding and fire risks at the site.

Infinergy Pacific revealed last month that it had submitted a fresh development application to Victoria’s Department of Environment Land Water and Planning, which has – in-between applications – become the responsible authority for large-scale solar developments in Victoria.

“In response to the Tribunal’s decision regarding the previous application, and in combination with additional Hydrology and Bushfire assessments, some changes have been made to the design of the Proposal when compared to the Previous Application,” the company said on the project website.

The changes include the location of the substation, battery and operations buildings, which have been rearranged to avoid an area of flooding, although they remain in the “same general location” as in the original plans.

The developers have also rerouted the main access point to the project in response to safety concerns raised by the local community at VCAT, and boosted the overall number of Access Points from five to eight in response to the bushfire assessment.

The number of water tanks has also been increased from one to eight in response to the bushfire assessment, while the inter-row spacing of the tracking system has been adjusted from 12 metres to 12.75 metres (south of the 220kV transmission line) and 13 metres (north of the 220kV transmission line).

Whether these changes will cut the mustard with DELWP remains to be seen, but the case is interesting, not least in that it helped to inform the state Labor government’s development of guidelines for large-scale solar farms, to help ensure projects targeted appropriate locations, were easily accessible to the grid and took into account land-use and ecosystems.

Those guidelines, finalised in July 2019, also included a framework for best practice on social licence, to help developers to engage effectively with communities and “ensure the least possible environmental and social impacts of their proposals.”

And perhaps most importantly, they acknowledged the huge amount of pressure being place on local governments that were ill-equipped – and under-resourced – to make the sort of planning decisions required for large-scale solar projects.

As the Corangamite Shire Council wrote in its submission on the Draft Guidelines, its grounds for refusal in the case of the Bookaar Solar Farm included “the absence of solar farm planning and policy guidelines by the state government,” which it said had led to a lack of direction for planning decision making.

“(It’s) not a bad proposal but it’s in an inappropriate locality,” said then Councillor and subsequent Corangamite Mayor – Neil Trotter in 2019. “There’s been a lot of emotion and finger-pointing in this, but strip that out and it’s a planning decision.”

In its project update last month, Infinergy Pacific noted that while some key changes had been made, the proposal for Bookaar remained “a design for a 200MW solar farm of the same dimensions and characteristics, located within the same design envelope as the previous planning application.”

The company said that, if approved, construction of the solar farm was expected to kick off sometime this year and take around 12 months to complete, with an operational period of around 28 years.

“Following the operational period, all above ground infrastructure would be removed from the site,” the statement says. “The decommissioning process would take approximately 12 months. As such, planning consent for the Proposal is sought for 30 years.”