Anyone who has had an experience on the sea-side with a couple of chips and a flock of seagulls can imagine what happened when the diesel generators spotted an opportunity to make money in South Australia on Monday.

Taking an advantage of network constraint imposed by the Australian Energy Market Operator, following a fault in the poles and wires in south east region of South Australia, diesel generators switched on and bid prices straight to the market cap.

And it was just like seagulls fighting over chips, as diesel generators such as Port Stanvac, Lonsdale and Angaston (all owned by the now federal government-owned Snowy Hydro), and Snuggery (Engie) piled into the market.

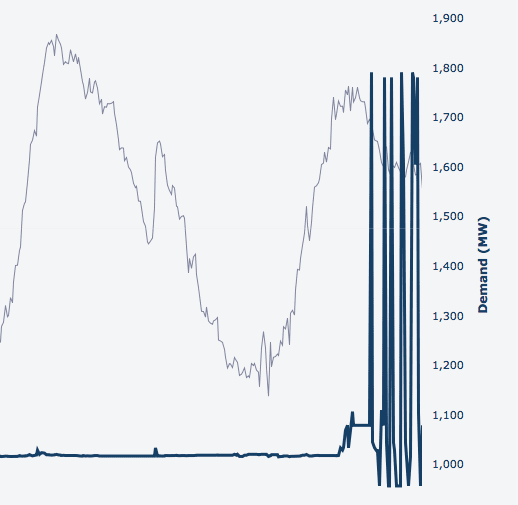

Over a period of six consecutive (30 minute) settlement periods (see graph above), the diesel generators bid the price up to or close to the maximum ($14,200/MWh) in the first five minute period, and then sent the price into negative in one of the last two five minute periods.

The first five minute bid at or near the market cap guarantees a hefty premium for their output over the full 30 minute period, when prices are averaged over the six 5-minute trading periods and decided.

The last five minute periods went into negative because the diesel generators, and all the other gas plants, are fighting to be the one assigned the benefit of that price premium, so they bid the price down to the market floor.

Happily for them, the market floor is much shallower than the market cap is high. Seagulls and chips.

A couple of points should be made about this:

The network constraint meant there was little that could be imported from Victoria during this time. South Australia was effectively a captive market.

Yes, there was little wind blowing at the time, and not much rooftop solar, which gave the diesel generators their opportunity. But it should be noted that the state’s biggest gas generator, Pelican Point (Engine), continued to have one 240MW unit absent.

Indeed, there was about 1,000MW of excess capacity available, as demand was not high, so this was not about a shortfall of supply, as there was more than enough gas capacity to meet demand, but many units couldn’t or chose not to operate.

So this was about the ability of a few players to take advantage of the market when a constraint is imposed by the market operator as a result of a network fault. Perhaps they were aggrieved and wanted to make up for the low prices of previous days.

What could be done?

More battery storage could help. The state has just one big battery in full operation, the Tesla big battery, but only 30MW of its capacity can play in this arbitrage market, so its impact is quickly overwhelmed (unlike in the FCAS market, where it has brought the gas cartel to heal).

A couple of virtual power plants – such as the 250MW proposed by Tesla for low income households could also help, and reduce costs for those households in the process.

And the federal government, which now owns 100 per cent of Snowy Hydro, could also do something, such as following the Queensland government and instruct its state-owned generators to behave.

The federal government likes to tell us how it is serious about reducing prices. So here is a perfect opportunity for it to demonstrate how genuine it is.

But Snowy probably needs the profits it makes in such events if it’s going to fund the construction of prime minister Malcolm Turnbull’s pet project, the $6 billion (and counting) Snowy 2.0 pumped hydro scheme.

Diesel plants are expensive, but don’t cost anywhere near the market cap of $14,200 – but they only operate a few hours a year, so they need to make money while they can. Consumers be dammed.

It also means that the transition to a 5 minute settlement period can’t come fast enough. Big consumers and battery storage developers argued that the 30 minute settlement period left the market exposed to exactly the sort of behaviour witnessed on Monday.

The fossil fuel generators. like Snowy Hydro, fought the change because it meant that their gas and diesel units would be denied peak pricing events like this. Snowy has also fought other price lowering initiatives such as demand management.

Unfortunately, the market rule-maker, the AEMC, says the change was so complex it would take years to introduce. It has no such qualms about the re-write of the NEM rules to accommodate the proposed National Energy Guarantee, something it expects to achieve in four weeks.

Update: The bidding patterns continued on for another four 30-minute intervals, following the same pattern – bid the prices up as high as possible in the first five minute, and down to the market floor (minus $1,000MWh) in the last interval, as the seagulls pecked each other for the scraps.

As the party looked set to fade, the price stayed at minus $1,000/MWh for three five minute intervals as the fossil fuel generators fought for the last chip.

It’s hard to imagine a more blatant example of (apparently legal) market gaming – the Australian Energy Regulator is obliged to look at it, but if current practice is any guide, will not likely file its report for a few months, or maybe even in early 2019. That’s how much they care about the consumer.