Australia is in a race to try and reach both its binding 2030 nationwide emissions reduction targets and its voluntary renewable energy targets, and if it is to have any chance of reaching either, it’s going to have to get a move on.

A semi-annual assessment of Australia’s climate efforts and green transition, by the leading global outfit BloombergNEF, provides a dispiriting assessment of the pace of the green energy transition to date.

Sluggish, slow and anaemic are the words it uses to describe the rate of investment in large scale solar, large scale wind, and new transmission – to the surprise of no-one watching it from close quarters. But it does beg a question: When exactly will the industry pick up the speed to reach its bold target of 82 per cent renewables by 2030.

Right now there is a lot of reasons why progress is slow. Slow planning approvals, slow connections, supply chain hiccups, surging civil construction costs, social licence issues, political and media attacks and – ironically – the wait for the federal government’s Capacity Investment Scheme to deliver its first mandates.

“Australia will have to increase the pace and depth of decarbonization across multiple sectors to meet its international carbon commitments and net-zero targets,” the BloombergNEF report says.

“Declining emissions at home and overseas are expected to have a profound impact on the Australian economy,” it notes, to underline the point that Australia simply can’t afford to put its collective head in the sand and pretend that fossil fuel economies are forever.

BloombergNEF notes that Australia’s emissions – if you exclude the dubious and some would say dodgy land use calculations – have fallen just three per cent over the last two decades.

That rate needs to accelerate significantly – the target is a 43 per cent reduction below 2005 levels by 2030 (including land use) and it won’t be done without a deep transformation of the grid.

Right now that is happening too slowly. The 23 per cent drop in grid emissions since 2005 has been about the only Australian success story on climate action, but it needs to ramp up significantly to deliver the new capacity.

The strongest part of the transition is what is occurring behind the meter, in homes and businesses, particularly with rooftop solar PV.

“Stubbornly high electricity retail tariffs, as well as falling module prices, have buoyed small-scale solar expectations in the near term, though BNEF maintains that residential solar installations peaked in 2021,” BloombergNEF says.

“Retail tariffs are beginning to soften from 2023 highs, as the impact of the 2022 energy crisis abates.” That assessment may be a little hopeful, given the experience of many with the switch to smart meters and the extraordinary tariffs thrust upon unsuspecting households.

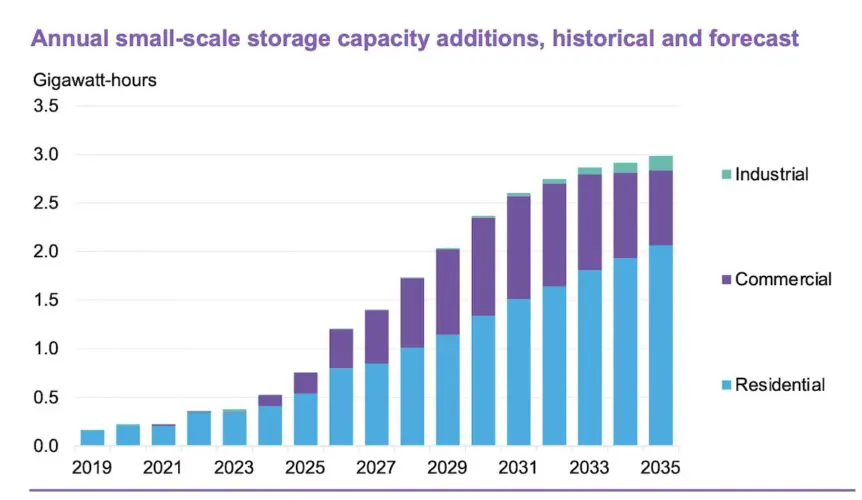

But while BloombergNEF expects the rooftop solar market to halve from around 2027 onward – because of the lower daytime grid power supplies (if ever they are passed on to consumers) and cuts in upfront rebates and export tariffs – it does expect the home storage market to boom.

“Australia’s behind-the-meter battery market continues to grow, though it remains anemic,” it says. “Battery installations continue to trail behind the extensive solar market, due to stubbornly high system costs and a lack of coordinated policy.

“However, installations are still steadily increasing on the back of improved technology offerings and sales processes from solar installers.”

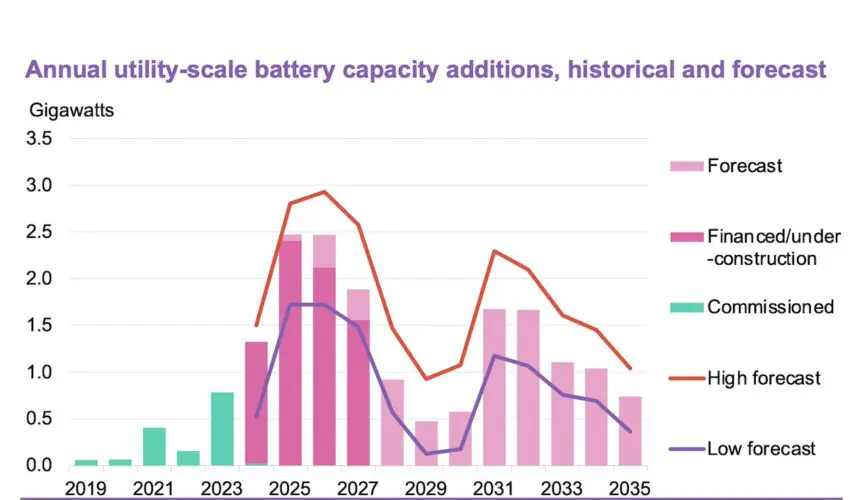

Surprisingly, BloombergNEF also casts doubt on the rollout of grid scale batteries, questioning whether the sector will maintain its growth after a strong performance in coming years.

“There are 7.8GW of utility-scale batteries under construction in Australia. In our base case, we forecast an additional 10.5GW of installed capacity by 2030, and 16.7GW by 2035, driven by concrete policy mechanisms, coal plant closures, improved revenue certainty and elevated power market volatility.

Its low forcecast – 12.5 GW by 2035 – is driven by revenue uncertainty, high project costs, market saturation and an inability to deliver on lofty state targets on schedule.

The high forecast could be nearly double that – 23.9 GW – driven by new business models, greater policy support and a growing need to firm variable renewable energy, and presumably (although it doesn’t mention this) the continued fall in battery storage costs.

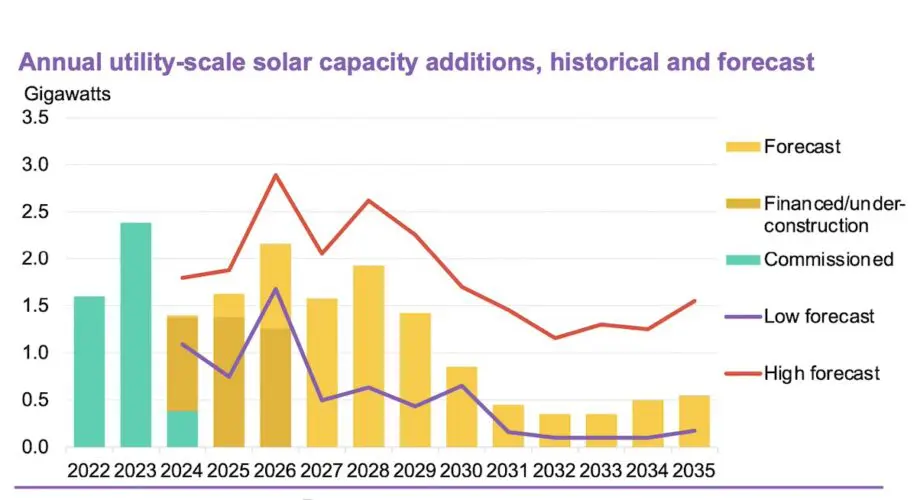

But the forecasts for grid scale solar and wind are mixed.

Grid scale solar has fallen significantly with just 389 MW of new projects commissioned in the first half of 2024, bringing the total operational capacity in Australia to 11.5GW.

BloombergNEF expects that to double over the next six years, driven by the CIS and W.A.’s accelerating transition from coal, but it expects just 2.2 GW to be added from 2031 to 2035. All states will end up with around double their existing capacity over the next 10 years, but there will be six-fold increase in W.A.

“BNEF has significantly lowered its solar additions forecasts post-2030 as the technology starts to reach higher saturation in the market and continues to self-cannibalise the value of its own generation. Additionally, rooftop solar build will continue to deplete midday demand, leaving less room for utility-scale solar in the market,” it says.

But things could look different in the high forecast, if coal closes early and green hydrogen takes off.

“Under the high forecast, coal is expected to retire faster than expected and Australia sees greater demand from electrolyzers for green hydrogen,” it says. Large scale solar capacity triples to around 33.4GW by 2035 in this scenario.

Wind energy has had an even slower rollout in recent times.

“The first half of 2024 saw 101 MW of new wind capacity come online, an uptick from the 0 MW seen last half, bringing total installed capacity to 11.7GW,” BloombergNEF writes.

“This continues to reflect the lull in investment in the post-pandemic years coupled with developmental delays.” But it expects wind capacity to nearly treble over the coming six years, to more than 30 GW, thanks to the CIS and other state based initiatives.

Queensland, it says, will see the biggest growth, with multiple gigawatt scale projects and less inhibited by transmission constraints resulting in an eight-fold increase in capacity in that state, albeit from a low base of 1 GW. NSW will install the most, up to 12 GW of new capacity.

“Both Queensland and New South Wales will see the rapid retirement of their coal fleet, creating greater demand for clean technologies like onshore wind,” it notes. Victoria and Western Australia also likely to add around 4 GW each of new wind capacity. South Australia, already at 70 per cent wind and solar share, will add another gigawatt.

“However, if challenges around slow grid buildout, lengthy permitting processes and social licensing issues remain, states could miss their 2030 and 2035 renewable energy targets,” it says.

But BloombergNEF is less confident about the prospects for offshore wind, predicting projects only in Victoria – the sole state to have a capacity target – and it says these may fall short and be slower than hoped.

“BNEF forecasts that Victoria will start commissioning offshore wind in 2033, installing 1.5GW by 2035 in our base-case scenario – failing to achieve its legislated targets of 2GW by 2032, 4GW by 2035, and 9GW by 2040.

“BNEF’s high scenario sees 3.3GW of offshore wind by 2035, just shy of the Victorian government’s target,” it says,. That assumes government support is adequate, the regulatory environment is well defined and infrastructure like ports and transmission is effectively built to support the burgeoning industry under this scenario.

But BNEF forecasts no offshore wind under the low scenario as the technology remains costly, government support is inadequate, regulation is unclear, and industry faces tight supply chains.