South Australia’s Port Augusta, with its abundant solar resource, has recently been pegged as the ideal location for the development of a concentrating solar thermal power plant – and understandably so. But what about a 2000 square metre greenhouse? It would seem an unlikely match for hot, dry Port August, yet while the region’s CSP plant proposal remains just that, an enormous solar-powered greenhouse has indeed been built – and it’s producing a fine crop of tomatoes.

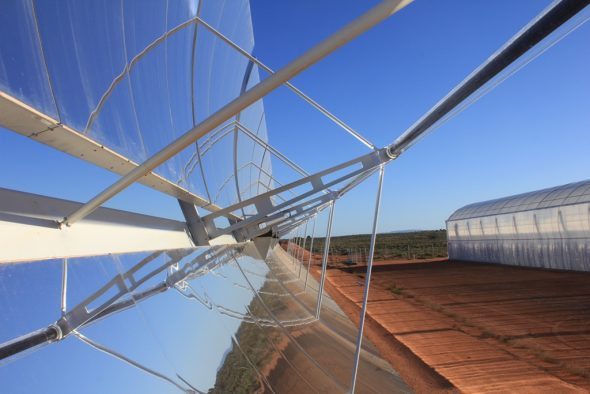

Behind the project is Sundrop Farms: a group of international scientists (and an investment banker) whose goal has been to devise a system of growing crops that doesn’t require a fresh water supply. How does it work? “It all begins with a 70 metre-long stretch of solar panels,” says Pru Adam’s on ABC Radio’s Landline: a series of concave mirrors which focus the sun’s energy onto a black tube that runs through the centre of the panels. The tube is filled with thermal oil, which is superheated up to 160°C, then pumped through the tube back to a little storage shed, where its heat is transferred to a water storage system. Some of this stored heat goes towards greenhouse temperature control, some to powering the facility, but most is used for desalination of the tidal bore water. When the heat goes to the thermal desal unit it meets up with relatively cold seawater and the temperature difference creates condensation.

“It’s pretty simple to understand,” said Reinier Wolterbeek, Sundrop’s project manager and head of technology development, in a 2010 television interview with Southern Cross News. “If you have a fresh water bottle from your refrigerator, and you put it in a room, then condensation forms on the sides. That’s more or less what we try to mimic over here; the cold sea water, from the ground, we put it through plastic tubes, we blow hot, very moist air against these plastic tubes, condensation forms on the tubes, we catch the condensation, and that’s actually the irrigation for the tomato crops.” The brine ends up in ponds and the salt can be extracted as a saleable by-product.

So, while this large-ish commercial-scale greenhouse (they’ve tested a smaller version in Oman), perched, as Adams describes it, “in the remains of flogged-out farmland,” really is an incongruous sight in Port Augusta, it’s there for good reason.

“We looked on a world map, and funnily enough, Port Augusta is the ideal place,” Wolterbeek told Southern Cross News. “It’s really close to the sea, so we have a lot of seawater available, and it’s very dry, which is good for the process of the technology.”

Philipp Saumweber, Sundrop’s managing director who is a former Goldman Sachs investment banker with an economics degree from Harvard, describes the project as unique. “Nobody has done what we’re doing before and to our knowledge nobody has done something even similar,” Saumweber told Landline. “What we think is so unique about our system is we’re not just addressing either an energy issue or a water issue, we’re really addressing both of those together to produce food from abundant resources and do that in a sustainable way.”

David Travers – CEO of the University College London’s Adelaide office, who became Sundrop’s chairman after being convinced of the merit of its technology – agrees. “Well it’s unique in the sense that it’s the only example we’re aware of in the world where there’s that complete integration of the collection of solar energy, the desalination of water, the production of energy sources from electricity through to heating and storage and then the growing of plants, in this case tomatoes and capsicums, in a greenhouse environment,” he told Landline. “It’s the totality of that system that makes it quite unique.”

Saumweber adds that while the project has higher fixed costs at the beginning, because of the use of solar technology and other technologies, “over time we have much lower running costs and we’re not exposed to the volatility in energy prices.”

Sundrop says their glasshouses can generate savings of between 5-15 per cent over fossil fuel-powered glasshouses, relying 100 per cent on solar during summer months, and supplementing diesel power for about 10-20 per cent of the time during winter months.

And with the technology proven, the company aims to expand the scale, says Adams. “There are plans before the local council for an eight-hectare, fully commercial glasshouse on this site. And there’s growing interest from international developers as well.”

And well there might be. As Wolterbeek said back in 2010, “water is a scarce resource and most of it goes to agriculture.” So making our own water for agricultural crops “looks like the way to go.” The next step for the company, Wolterbeek tells Landline, is an eight-hectare greenhouse: “that’s 40 times larger than what we have now. That’s all doable; financially we’re pretty close.”

The company’s broader goal, says Saumweber, “is to grow in this sustainable manner ourselves and operate the greenhouses. “So, we’re very much looking forward to building a base here in Australia, but also expanding the knowledge and the experience that we’ve gained here to other parts of the world.”