Rio Tinto has finished building a solar farm in Canada and will begin construction on two more solar projects in the Northern Territory, as the iron ore miner installs solar to support end-of-life operations at various mines.

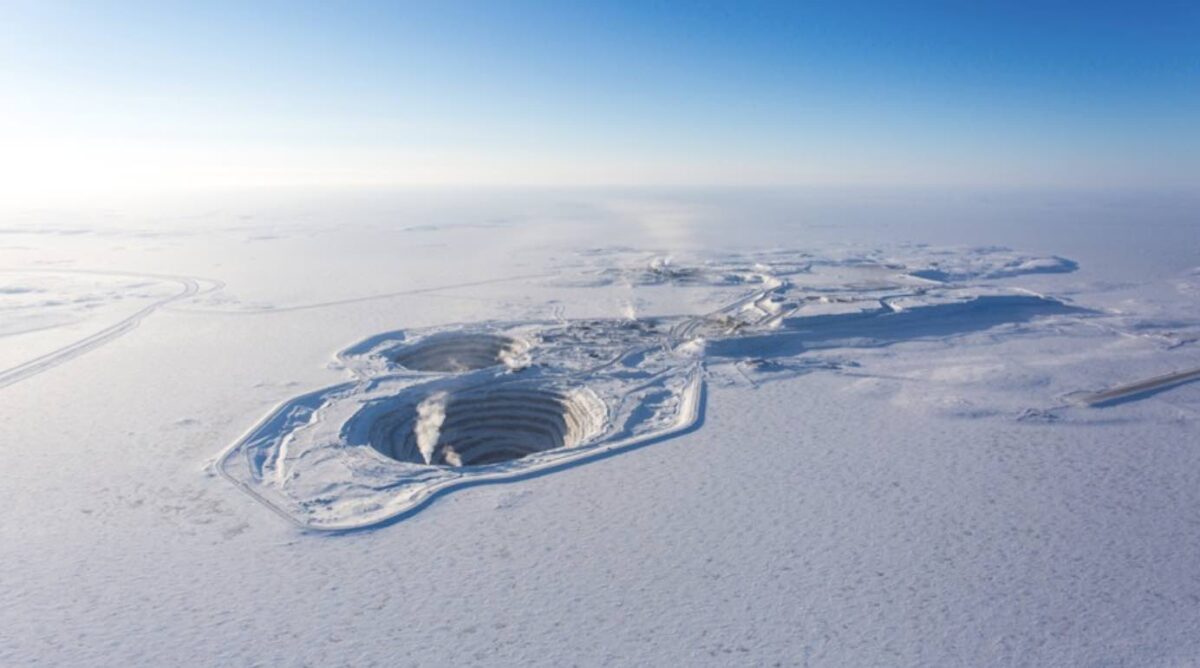

The Canadian project is a 3.5 megawatt (MW) generator to provide 25 per cent of the Diavik diamond mine’s energy needs as it shuts down, and is currently the largest off-grid solar power plant in the Northwest, Yukon and Nunavut territories.

Rio Tinto plans to close the mine between 2026 and 2029, after which it’s unclear how the solar, and associated wind, projects will fit into the local energy network.

“Diavik is working with the Government of the Northwest Territories and community partners to determine how its renewable energy infrastructure can best benefit the region following closure,” Rio Tinto says.

The bulk of the $C4 million ($A4.4 million) solar project was paid for by a $C3.3 million grant from the Government of the Northwest Territories’ Large Emitters GHG Reducing Investment Grant Program.

Construction started in February. The project uses bi-facial panels which generate energy from direct sunlight as well as from the light that reflects off the snow that covers Diavik for most of the year, and reduce diesel consumption in the area by 1 million litres a year.

It’s a set-up that provides a solar blueprint for other mines in northern Canada, says Ben Power, who runs the company which built the project, Solvest.

Two new solar farms for East Arnhem Land bauxite

Rio Tinto has also signed off on building two new 5.25 MW solar farms on Gumatj and Rirratjingu country on the Gove Peninsula in the Northern Territory.

In this case however, the plan is for the projects to underpin electricity supplies in the Gove area after the bauxite mines are closed around 2030.

Aggreko will start building the two solar farms this month on land leased by Rio Tinto, with the right to own and operate them for a decade.

“The Gove solar project is part of our shared vision with traditional owners to leave a positive legacy for the Gove Peninsula communities after bauxite mining ceases,” said Rio Tinto Gove operations acting general manager Shannon Price.

“We’re excited to work with the Gumatj and Rirratjingu clans to provide an opportunity to secure alternative electricity generation assets on their country and to discuss opportunities to commercialise energy infrastructure in the future.

“We intend for these farms to underpin sustainable power for the region beyond mining.”

The two solar farms are expected to reduce the region’s annual diesel consumption by about 20 per cent, or 4.5 million litres a year, and lower annual carbon emissions by over 12,000 tonnes, or the equivalent of taking 2,800 internal combustion engine cars off the road.

Miner or electricity company?

Like many miners, Rio Tinto is becoming a big buyer of renewables.

In January the company signed a contract to buy all the electricity from what will be the biggest solar project on Australia’s main grid – the 1.1 gigawatt (GW) Upper Calliope solar farm near Gladstone in Queensland, that will help power the mining giant’s smelting and refinery operations there.

Then it almost topped its own record the following month by agreeing to buy 80 per cent of the output of the 1.4 gigawatt (GW) Bungaban wind energy project which is planned by Windlab, a developer majority owned by iron ore magnate Andrew Forrest.

The solar deal is the largest solar power purchase (PPA) agreement in Australia to date, while the Bungaban PPA is the largest for wind.

Rio Tinto has also issued a tender for similar scale wind and solar projects to help power the Tomago smelter in NSW by the end of the decade, and is seeking up to a gigawatt of new capacity for its huge iron ore operations in the Pilbara.

Buyers like these are reducing the gap Australia faces in achieving national and state renewable energy targets, with industrial demand such as the massive tender to repower the Tomago smelter near Newcastle also shifting the dial on renewables development.