As the adage goes, all good things must come to an end: solar panels, with an average lifespan of 25 to 30 years, are no exception.

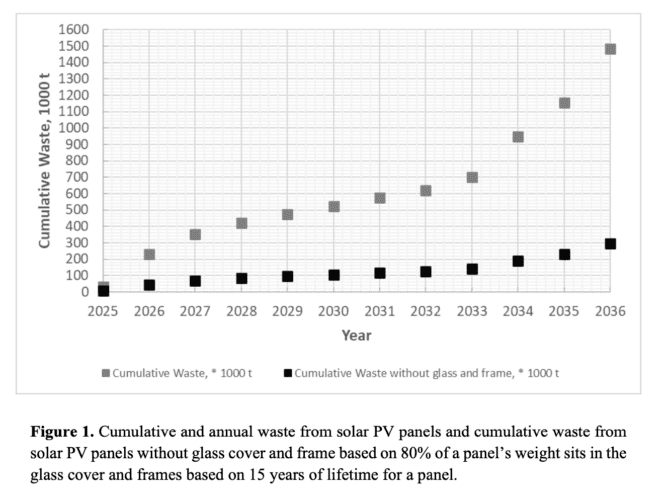

That means the solar industry faces an approaching problem. With an estimated 100,000 tonnes of end-of-life Australian solar panels due to be dismantled by 2035, what will be done with all that waste?

Australia currently has about 80 million solar PV panels installed, and the market share of renewable energy sources has overtaken gas generation for the first time. The solar boom of 2010-2012 means a massive surge of end-of-life panels is expected after 2030.

“Australia has one of the highest uptakes of solar panels in the world, which is outstanding, but little thought has been given to the significant volume of panels ending up in landfill 20 years down the track when they need to be replaced,” says Peter Majewski, a Professor of advanced materials and energy at the University of South Australia (UniSA).

According to Sustainability Victoria, Australia’s existing infrastructure for the recycling of solar panels can only reclaim up to 17% of a panel by weight, and most of that is made up of the panel’s aluminium frame and junction box.

The Remaining 83% of the materials, which includes tempered glass, silicon and polymer back sheeting, are not currently recyclable in Australia.

But it doesn’t have to be that way: According to Majewski, some 80% of panels could easily be recycled using today’s infrastructure – especially if the brittle, easily shattered tempered glass is handled with care – and more if the industry gets innovative.

“There’s not actually a lot of materials in there,” he says. “The main thing is the aluminium frame and the glass panel, then the more problematic materials like the polymers that the solar cells are embedded in for waterproofing.”

There are two main polymers involved in waterproofing, one of which, on the back-sheet of the panel, is known as fluorinated polymer, and is very difficult to dispose of safely – when burned, it produces a toxic gas that can cause irritation, headaches, nausea and, in extreme cases, pulmonary edema.

It’s difficult but not impossible to recycle these polymers, and Majewski says it can be done using pyrolysis (the heating of a material in the absence of oxygen) to burn it off and collect the oils and resins that are produced.

Then there’s the solar cells themselves, which are mostly made of silicon. Silicon is also the most common conductor used in computer chips.

While it’s abundant on Earth, silicon could be retrieved from end-of-life panels instead, resulting in far less environmentally damaging resource extraction. But, given silicon recycling infrastructure does not yet exist in Australia, a whole industry would need to grow up around it.

“The demand for silicon is huge, so it’s important it is recycled to reduce its environmental footprint,” says Majewski.

Though the problem of building a silicon recycling sector is no small feat, Majewski says such an industry has the potential to be a commercial success. And there’s nothing about silicon that makes it inherently un-recyclable: all that’s lacking is the impetus.

“About three billion solar panels are installed worldwide, containing about 1.8 million tons of high-grade silicon, the current value of which is $US7.2 billion. Considering this, recycling of solar PV panels has the potential to be commercially viable.”

There are also trace metals including copper-nickel alloys and, in some older panels, silver, which could be retrieved.

“So it’s really just a handful of materials, it’s not that difficult,” says Majewski, optimistically. The problem, of course, is building a viable recycling industry around solar panels, and to do so will require legislating that a high percentage of the weight of the panels be recycled.

That’s what Majewski and his co-authors are proposing in a new paper published today in AIMS Energy. The paper calls for a comprehensive “product stewardship scheme” for solar panels, identified as a priority by the federal government, that could in theory legislate whole-of-life responsibility for the materials in a solar panel, and place it on the shoulders of the producer.

Such a scheme has been in the works for a while. The massive anticipated waste problem associated with the solar boom was placed on the environment minister’s Product Stewardship List in 2016: but thus far, despite an explicit statement that the scheme must be finalised by June 2022, no such scheme has materialised.

Majewski says such a scheme must be mandatory to have a hope of working, and that similar such schemes for other clean energy technologies can act as a model.

“Several European nations have legislation in place for electric car manufacturers to ensure they are using materials that allow 85 per cent of the car to be recycled at the end of their life,” he says. “Something similar could be legislated for solar panels.”

Majewski says a scheme like this would incentivise the industry to increase its recycling capacity. While there are just six companies in Australia who currently recycle solar panels and products, Majewski is confident the industry would grow if it had assured income through legislated recycling.

“It’s not currently a big business, because the numbers are still fairly small,” he says. “But within the next five or 10 years the numbers will increase significantly. If there’s legislation which tells the consumers you have to bring your old solar panels to recycling, then the recycling industry has a more assured flow-in of materials.”

Majewski also recommends the introduction of a landfill ban specific to solar PV materials, similar to the existing ban in Victoria.

“Landfill bans are already in place in Victoria, following the lead of some European countries, encouraging existing installers to start thinking about recyclable materials when making the panels.”

Majewski says that landfill bans can be a powerful tool provided they don’t simply divert the waste to other locations with less stringent regulations. The paper also recommends serial numbers that can track the history of solar panels and monitor their recycling.