A record amount of solar capacity and renewable power was installed across the world in 2017 – as the cost of both wind and solar became competitive with fossil fuels – but it still is not enough, a major new report has found.

The annual Renewables 2018 Global Status Report from REN21, a renewables policy organisation, notes that a record 98GW of solar capacity was added, as well as 52GW of wind, and a total of 178GW of renewables.

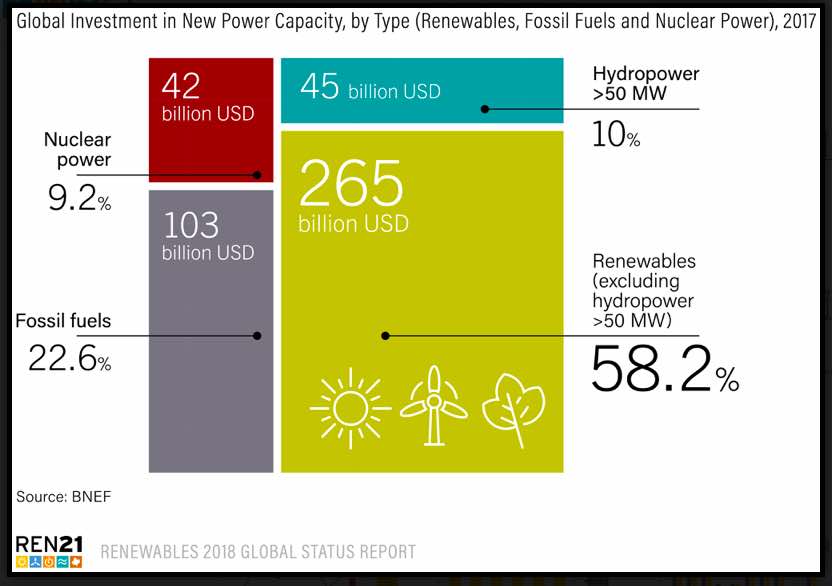

Including large hydro, this amounted to $US310 billion of new investment, nearly twice that of new fossil fuels and nuclear capacity, and the global share of renewables is now at 23 per cent, with wind and solar providing 7.4 per cent.

But while the growth in renewables electricity was pleasing and continues the transformation of the electricity sector, REN21 says it is concerned by the lack of change in transport, cooling and heating, which means the world is lagging behind its Paris climate goals.

“We may be racing down the pathway towards a 100 percent renewable electricity future but when it comes to heating, cooling and transport, we are coasting along as if we had all the time in the world. Sadly, we don’t,” said Randa Adib, executive secretary of REN21.

Adib’s concern was shared by investors representing $26 trillion of assets under management, which used the prelude to the G7 Summit in Canada to call for governments to step up their ambition and action to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.

“The global shift to clean energy is underway, but much more needs to be done by governments to accelerate the low-carbon transition and to improve the resilience of our economy, society and the financial system to climate risks,” investors wrote in a joint statement.

Emma Herd, the CEO of the Investor Group on Climate Change, the Australian chapter of this group, says investors are stepping up in unprecedented numbers, but could do so much more if governments acted too.

“Investors could do even more if governments delivered the policies required to effectively manage climate risk and accelerate investment in low-carbon solutions.”

Labor’s Mark Butler said this was a clear reproach to Australia’s Coalition government, which refuses to lift its weak 2030 target even though most analysts say it will be largely met – in the electricity sector at least – by 2030.

“The Turnbull government’s weak National Energy Guarantee is projected to deliver no new large-scale renewable energy investment over the 2020s,” he said in a statement.

“And far from being on track to delivering their weak targets, according to the government’s own data emissions are projected to increase all the way to 2030.”

The REN21 report said of particular concern was global energy demand and energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, which rose for the first time in four years in 2017, by 2.1 per cent and 1.4 per cent respectively.

“In the power sector, the transition to renewables is under way but is progressing more slowly than is possible or desirable,” it says.

“A commitment made under the 2015 Paris climate agreement to limit global temperature rise to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels makes the nature of the challenge much clearer.

“If the world is to achieve the target set in the Paris agreement, then heating, cooling and transport will need to follow the same path as the power sector – and fast.”

The scale of the problem is illustrated in this chart above, which shows all energy usage, including the oil-dominated transport sector, and the traditional biomass for heating and cooking.

The heating, cooling and transport sectors – which together account for about four-fifths of global final energy demand – continue to lag behind the power sector.

Around 92 percent of transport energy demand continues to be met by oil and only 42 countries have national targets for the use of renewable energy in transport.

However, increasing electrification is offering possibilities and more than 30 million two- and three-wheeled electric vehicles are being added to the world’s roads every year, and 1.2 million passenger electric cars were sold in 2017, up about 58 per cent from 2016.

Currently, electricity provides just 1.3 per cent of transport energy needs, of which about one-quarter is renewable.

There is little change in renewables uptake in heating and cooling. National targets for renewable energy in heating and cooling exist in only 48 countries around the world, whereas 146 countries have targets for renewable energy in the power sector.

Small changes are under way. In India, for example, installations of solar thermal collectors rose approximately 25 per cent in 2017, as compared to 2016. China aims to have 2 per cent of the cooling loads of its buildings come from solar thermal energy by 2020.

“To make the energy transition happen there needs to be political leadership by governments,” says Arthouros Zervos, the chair of REN21.

“For example by ending subsidies for fossil fuels and nuclear, investing in the necessary infrastructure, and establishing hard targets and policy for heating, cooling and transport.

“Without this leadership, it will be difficult for the world to meet climate or sustainable development commitments.”