One of Peter Dutton’s key selling points for nuclear power, its “always on” reliable generation of electricity, has been put to the test in a new analysis, which found that a fleet of modern nuclear plants is, on balance, about as reliable as a fleet of wind and solar farms – if those wind and solar farms were in the midst of a very bad renewable energy drought.

The analysis by David Osmond, a senior wind engineer who runs weekly simulations of Australia’s main electricity grid, compared outages experienced by solar and wind during renewables droughts – known as “dunkelflaute” – to outages in nuclear energy generators.

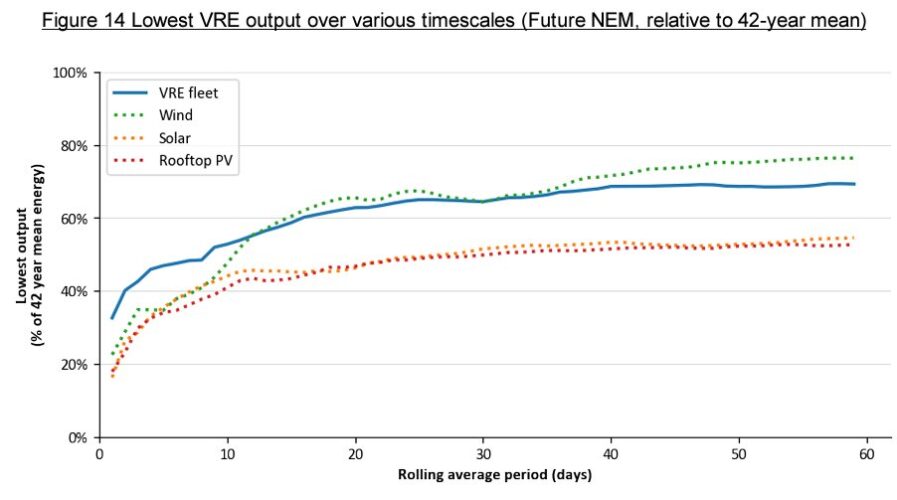

For the renewable energy side of the equation, Osmond draws on Griffith University modelling of 42 years of synthetic wind and solar data quantifying the risk of renewable energy droughts to Australia’s future energy supply.

The nuclear side of the equation is based on Osmond’s own analysis of seven years of daily nuclear fleet data since 2018 from European countries with four or more reactors.

Noting there has been more investigation into renewable droughts and the reliability of solar and wind in Australia than nuclear, Osmond sought to examine the “worst case scenario” for nuclear – periods with simultaneous issues with multiple reactors.

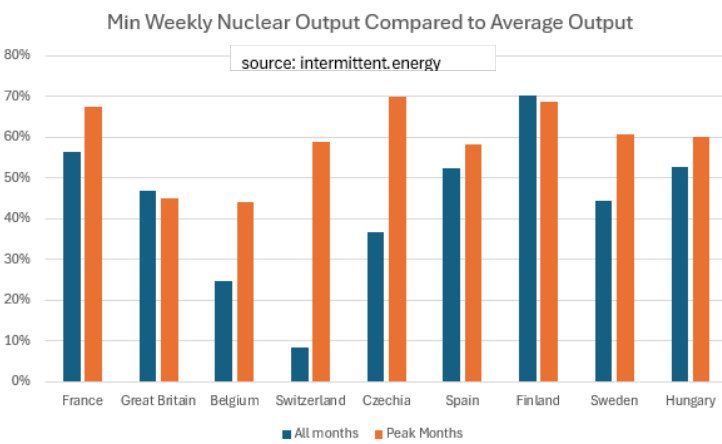

Using fleet data grouping outage periods into peak and off-peak months, Osmond found that during its “worst week” in any month, nuclear experienced a reduction to 8% to 70% of average output, and 44% to 77% in peak months – comparable to the “worst week” experienced by renewable energy over the modelled 42 years.

“Nuclear isn’t 100% reliable,” Osmond writes on BlueSky. “Multiple outages can occur simultaneously, even during peak demand months.

“Analysis of European nuclear data suggests weekly fleet output during peak season can drop below 60% of average levels. This is comparable to the effect of a bad renewable drought on wind+solar generation in Australia.”

Source: David Osmond

Osmond says that when it comes to wind and solar, the data shows “the worst week for wind and solar is likely to be about 50 percent of the long-term average” making the two technologies roughly comparable.

Source: David Osmond

“I found for the countries that I studied, most of the nuclear outages in the last eight years of data I looked at was equivalent to a renewable drought in Australia,” Osmond said.

“When I looked at the data for nuclear, the worst week for nuclear in peak season, for most countries, seemed to be about 60 percent of average.”

Osmond said this was roughly consistent across jurisdictions with Ontario, considered an exemplar among the global nuclear industry and its supporters, broadly similar to Europe but with much less seasonal variation.

A caveat, he said, was France and its 55 reactors where operators practice ramping to match output with demand.

Though this complicated the analysis, Osmond said he reviewed the data to verify the results were reflecting outage not ramping or scheduled shutdowns.

Nuclear outages can occur either on a schedule where maintenance needs to be carried out, or may be “forced” either through the discovery of a problem, a technical fault, an emergency or an external factor that knocks one or several reactors offline, sometimes simultaneously.

Some reactors like Finland’s new Olkiluoto 3 – a reactor that took 18 years to build and forced its French developer to be bailed out – have experienced technical faults that have periodically sent it offline. And According to Professor M.V. Ramana, a physicist from the University of British Columbia and author of the book Nuclear is Not the Solution, says that nuclear plants are also vulnerable to climate impacts.

“Nuclear plant operations are being challenged by hurricanes, forest fires – things of that sort,” Professor Ramana says. “But that trend has not led to as dramatic declines in power capacity as was the case in France.”

In August 2022 a combination of drought and heatwaves forced half the reactors offline as the water in rivers warmed to the point where it could not be used for reactor cooling.

“Nuclear plans will need an external source of water for cooling,” Professor Ramana says. “The challenge is much more for nuclear power plants that are inland where they have to rely on lakes or rivers, where the temperature can go up much more in summer.

“And that’s what we’re seeing in the case of countries like France and Western Europe in general. Even the French authorities expect that this problem is going to get worse, so they are making plans for that.”

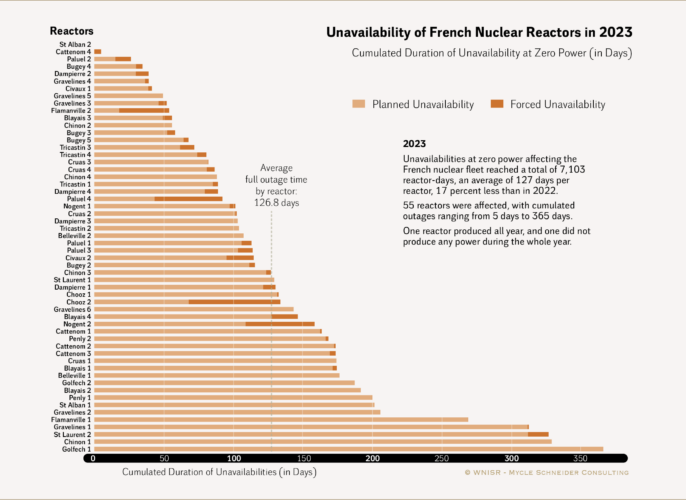

France’s nuclear fleet has particularly struggled in recent years. According to the World Nuclear Industry Status Report, its 55 reactors were subject to outages lasting between five days and a year in 2023 and only one reactor, Saint Alban-2, produced all year round.

The report found that on any given day, at least 11 units were offline across all of France with the highest number of reactors shut down on the same day reaching 28. When it came to partial days offline, 19 or more units were offline for least part of the day for 252 days, or 69% of the year.

Though nuclear has a higher capacity factor – the ratio of energy output over a given time – than solar and wind, Osmond says much of the discussion of nuclear in Australia has falsely assumed it is 100% reliable.

These assumptions will skew any modelling, he says, as they do not account for what it takes to manage the variability of both technologies.

“If you want a solution that doesn’t rely on gas, you can overbuild renewables,” Osmond said. “If you build renewables to cover twice your annual needs, that means even on your worst year, you’ll have enough generation.”

“Likewise, if you wanted to rely entirely on nuclear you’d need to overbuild your nuclear so that if you have multiple simultaneous outages, you can make sure you’ll have enough power during those occasions or where power is extreme.”

“Of course having 50% overbuild of nuclear is far more expensive than 100% overbuilding of renewables.”