As the sun rises over Victoria’s rugged coastline, a new era dawns – one powered by the pressure equalisation that we call wind. Australia’s offshore wind industry is not a distant dream; it’s taking shape now.

At the forefront stands Victoria, poised to harness the mighty Southern Ocean’s Roaring 40s to propel the nation toward a clean, more sustainable future. Well done Victoria!

Echoing this, federal energy and climate minister Chris Bowen announced the granting of feasibility licences to 6 offshore wind projects in the Gippsland region this month, with a potential further 6, subject to First Nations consultation.

The government says the 12 projects could generate a massive 25GW of electricity, and 15,000 jobs during construction with another 7,500 ongoing. But how do we bridge the gap from this vast potential to financially and practically feasible projects producing green electrons?

Victorian minister for energy, Lily D’Ambrosio, instrumental in accelerating the state’s energy transition, is motivated by the need to replace the end-of-life, high emissions lignite industry, and redeploy the skilled workforce, grid connections and community resources this frees up.

Credit to the minister for displaying bravery in adopting a vision for new technology at mega scale to reorient and underwrite Victoria’s industry, focusing on long-tail creation of better jobs, livelihoods, prioritising domestic supply chains and sustainable energy solutions over short term gains.

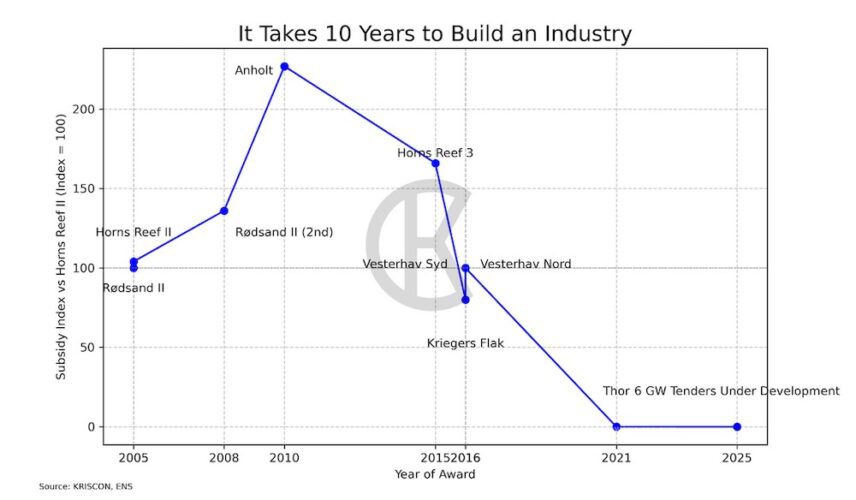

That is a model the co-author’s origin in Scandinavia relates to: Denmark adopted offshore wind as a response to the oil crisis in 1971 – Denmark’s ‘freezing platform’, as its ability to warm itself was potentially compromised – a version of the ‘burning platform’ the world is experiencing now as the climate crisis escalates.

In pursuit is NSW and recently Western Australia, each presenting their set of strong resources and offtake fundamentals. Combined, this provides the critical mass of multiple projects that can be developed sequentially to optimise supply chain, ensuring cost reductions through ‘learning by doing’ domestically, across a series of projects.

Cutting through the foggy public messaging, we provide an honest, unbiased, and easy to digest WHY, WHAT and HOW on offshore wind.

The burning platform

Dane Henrik Stiesdal, the founder of Stigsdal, started toying with modernising onshore wind turbines in the 1970. 25 years later in the mid 1990s, turbines were erected offshore in the strait between Denmark and Sweden.

It was a crisis-response, not a hippie-gone-bonkers gimmick. The oil-crisis in 1971 meant kids roller-skated on highways during car-free Sundays due to petrol not being available. Denmark had to diversify energy generation to stay warm. It appealed to the country’s primal emotion of fear long before Denmark thought to make an industry of it.

What is the Australian equivalent?

Keeping the lights on! Electricity generating coal power plants are approaching end of life and retiring. Even if, hypothetically, decarbonisation targets were scrapped, coal could not be rebuilt in time to keep the lights on, and no sane private investor would finance it.

That is it, simply. Emissions-induced climate change does not, yet, have sufficient collective impact on Australians’ lifestyle to motivate change. And fossil fuel exports are still too important, given Australia is the third largest exporter in the world.

But extreme weather events are becoming more frequent, more severe and far more costly, and as this understanding builds, it’s a double whammy, but one that we can prepare for, and even as a nation benefit from. But how do we do it efficiently?

Aligning political will and policy with the imperative to transition, minister Bowen and Treasurer Jim Chalmers are doing the right thing – recognising we are on the ‘burning platform’, and taking decisive action to mitigate it. But we need an ambitious whole-of-government approach, urgently. And an end to the climate wars.

For a resource rich country like Australia, accustomed to the ability to ‘open the taps’ when stimuli are needed, it is inconvenient and unnatural that significant public financial support is required to underpin decarbonisation of our electricity system.

But we have the absence of a clear, appropriate carbon price, both domestically and in international trade. So an intervention is needed, otherwise the platform will burn away, and Australia will meet an inevitable transition ill prepared. And other nations will seize the prize.

The opportunity, the history, and the future

Australia has the wind resources, is strong enough to lift the policy burden and has the financial wherewithal to establish an offshore wind industry of sufficient critical mass to attract world scale investments from global leaders.

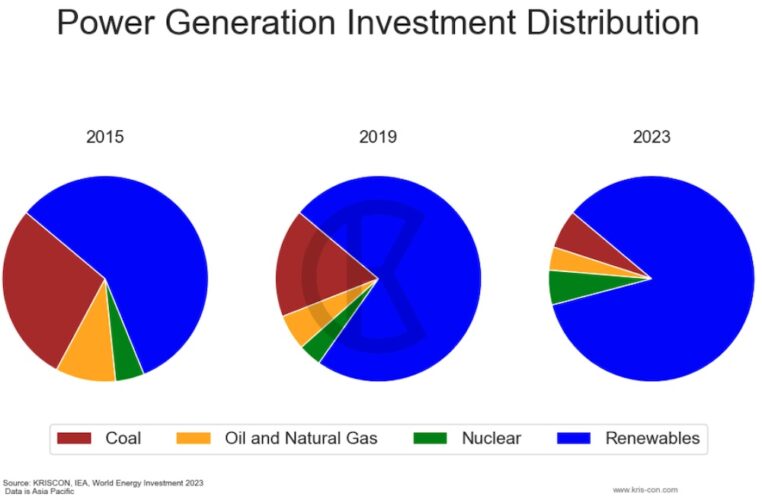

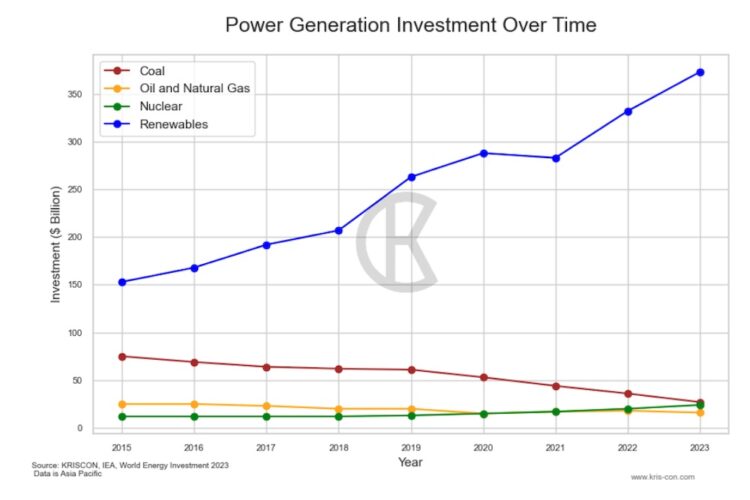

Aussies being late to the offshore wind party is an advantage. Early movers had to deploy and accelerate subsidies to create the global knowledge until the industry got big enough to have its own pulse.

The UK and Denmark are examples. Recent projects, on the other hand, have paid their way, requiring little then no public support.

Australia can leverage overseas learnings and shorten the length of project development and the timeframe requiring subsidies. Going too far the other way, however – expecting commercial projects from the get-go absent a price on carbon emissions – is an unrealistic idea with disproportionate risk on the first-of-a kind mover, compromising industry take-off. We need to avoid that.

A federal offshore wind target of no less than 12GW over the 10 years to 2038, a meaningful budget to deliver it, 25-year offtake underwrites and an attractive capital support for first projects in each state would do the trick of establishing the critical bridge from potential to established industry and re-skill our workforce into industries of the future.

When asking why we should consider support for this tech platform, we need to remember the burning platform. Offshore wind can close the gap as we transition from coal power, keeping the lights on. The narrative of green and cheaper power is enhanced by the prospect presented by offshore wind of power supply security and its ability to get Australia past the net zero goalpost.

Getting from 95% to 100% value, not cost

A common and important question that comes up often is why more expensive offshore wind should be considered. Beyond leveraging existing grid transmission considerations, offshore wind will sit at the high end of the onshore wind price range, and it will be considerably higher than solar.

So why consider it? While price is king in the electricity consumer market, it is not king when we factor in the burning platform scenario as the climate crisis escalates and the need for a range of solutions to deliver diversity to ensure energy security and reliability.

Here, the ultimate currency is emissions, and the target is zero, or less. Offshore wind can deliver multi-gigawatt zero-emissions electricity with a generation platform that complements the generation profile of onshore, in proximity (20km) to key demand centres, with social license and environmental impact profiles much easier to digest than similar onshore of the same scale, reducing strategic land use conflict issues.

Combining the unique selling points, offshore wind will have a critical role in decarbonising the energy mix as we seek solutions beyond the 82% by 2030 target, enabling us to get across the line to net zero, and, in the interim, provide electricity at scale close to demand.

The critical path and the developer’s dilemma

Certainty and investment readiness shadow each other. When one moves, the other follows. This is the wizardry that happens at the core of developers who look to develop, build, own and operate – a continuous trim of variables affecting cost of capital, Internal Rate of Return (IRR) expectations.

Australia has the huge superannuation capital base required, it just needs to be unlocked and enabled. It is a game of chess, where each development expenditure unveils more certainty, triggering a new development budget and so on. This goes on until risk is controlled or priced, and the project is Ready to Build. Simple enough, but very hard to do.

A common misconception is that this is a developer-risk, but it cascades through the rest of the supply chain too.

Ports and their shareholders need proof before funding expensive expansions. Turbine manufacturers cannot build or allocate capacity without certainty. Major steel components manufacturers have the same issue as for turbines. Transmission grid owners won’t build if they don’t have a guarantee of demand. And it takes time and investment to educate and train a workforce.

Money talks. A national target with a budget to deliver is what is required to get the boardrooms of the aforementioned players to shift gear. Early-stage developments are relatively cheap, and bringing industry fast to the point where serious transactions happen is crucial. Then the conversation will shift from ‘castle in the sky’ to the physical creation of tomorrow’s energy industry.

With a government target, Australia can choose how to illustrate commitment by supporting along the critical path, if it is decisive and meaningful.

In principle, it should not matter to consumers whether the support happens as a Contract for Difference to developers, as port expansion grants, OEM manufacturing commitment, education of technicians or a combination of all above. The logic is that at the end of the day, all these variables are absorbed in the project models anyway; it is either sufficient support, or not.

The jobs

In a previous job as an expert in renewables with the Foreign Ministry of Denmark, the co-author travelled across Australia, visiting the states considering offshore wind.

Everywhere there was talk of the expectations for job creation. Considering that Australia’s unemployment rate is still low at 4.1%, and the news is filled with stories of immigration required to cover worker shortfalls, this was puzzling, until local authorities in Gippsland in regional Victoria, where offshore wind is now taking shape and expected to create opportunities clarified that the opportunity is about creating quality local replacement jobs over time, not more jobs.

Understanding this difference points to an imperative for Australia to build and retrain the technical workforce capacity to install, operate, and maintain the 12GW offshore wind fleet. With opportunity and knowledge comes reduced fear of change.

The ports

Having the right port capacities is key on the critical path to unlocking offshore wind. Two things characterize a port executive’s dreams: volume and speed, such as containers or bulk materials moving as fast as possible. Offshore wind, by contrast, is relatively few items moving slowly. This can be mitigated with initial support, and better yet, by preparing port expansions for multi-source revenue.

Hinterland and quay walls can be made to support RoRo (roll-on, roll-off), military operations or hydrogen/ammonia export in between offshore wind installations. Port managers will, however, whether private or publicly owned, have the same question as turbine manufacturers, universities, and the rest of the supply chain.

Are we building for just one or two 1GW projects, or are we creating industry with 12GW over a decade?

The supply chain and turbine manufacturing

The joke had always been “what are we going to do when the solar levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) reaches zero”. The assumption was that innovation and scale will drive LCOE to its limit, zero.

However, steel, copper, polymers, composites, and logistics are all critical components of any renewable energy platform, and from 2020 they started increasing in cost, causing original equipment suppliers to experience significant losses. It awoke the world to a new normal where availability and diversity, and not just cost, is valued. Where domestic supply chain options have geopolitical interests the market alone can’t value.

When discussing availability with turbine manufacturers, they too point to national targets and the necessity for a budget.

With 12GW of offshore wind spread over 10 years, Australia passes the global scale bar for any turbine manufacturer to either establish an Australian manufacturing site – the preferred option, driving local jobs and a plethora of subcontractor opportunities – or earmark capacity elsewhere to serve the Australian market.

Victorian energy minister Lily D’Ambrosio and minister Bowen have taken a huge step up the ladder of the Developer’s Dilemma with the Gippsland feasibility licences.

What is equally encouraging is that their messaging is that they understand that we still have some distance to climb before we have a successful offshore wind industry established, as we move from talk to green electrons generation.

Mads Prange Kristiansen is MD at KRISCON, which specialises in data-driven pathways to renewables implementation and worked extensively on energy policy with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark in Australia.

Tim Buckley is Director of Climate Energy Finance, an Australian public interest thinktank.