EnergyCo, the NSW government body in charge of the rollout of its renewable infrastructure plan, says a new study indicates that the country’s first renewable energy zone in the central west of the state could host an extra 2 gigawatts (GW) of wind, solar and storage capacity.

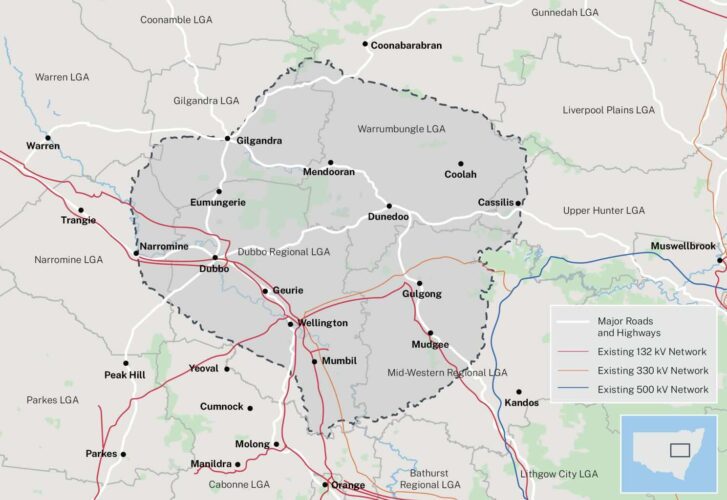

The revelation is included in a newly published, but little publicised, “headroom” study that looks at the capacity than can be accommodated in the Central West Orana zone, based around Dubbo and Dunedoo, which has just received its federal environmental approvals.

The capacity of the CWO renewable energy zone was originally flagged at 3 GW, but the NSW government decided to double that capacity to 6GW, with 4.5 GW being the interim target.

Those figures relate to its maximum transfer capacity. The question for planners is how much wind, solar and storage can be accommodated within that guideline, given that they will rarely, if ever, be generating at full throttle at the same time.

The first estimate put the hosting capacity for a 3 GW transfer limit at 5.84 GW of wind, solar and battery storage. The new study puts the hosting capacity for a 4.5 GW transfer limit at 7.7 GW of wind, solar and battery storage.

This is made up of 3.05 GW of solar hybrid projects (solar combined with battery storage, which appears to be the preferred model for new solar projects in the REZ), 2.95 GW of wind capacity, and 1.7 GW of stand-alone battery capacity (with an average two hours of storage).

The estimates are based on an assumed “curtailment” rate of just 0.25 per cent, well below the promised maximum curtailment rate of 4.37 per cent.

This is important given that projects built within the REZ will have to buy grid access rights, which are supposed to protect them from grid congestion and investors and bank lenders will want clarity on this.

EnergyCo says it believes its estimates are conservative, and is seeking feedback from industry players by the end of the month.

However, judging by the reaction to a LinkedIn post discussing the new headroom calculations, not everyone in the industry is convinced that the capacity can be hosted and kept within the assumed curtailment limits.

The main concern is the ability to transfer that capacity to the load centres, notwithstanding the presence of the huge 850 MW, 1680MWh Waratah Super Battery, which will act as a kind of giant shock absorber and be calibrated to allow transmission lines to operate at full capacity.

“NSW REZs will fail because they will be over filled as soon as the lines are built,” said one critic. “7.7 GW in CWO? That cannot possibly make it to the load centre without massive curtailment elsewhere.”

That critic says the blockage, even if it did not emerge on the transmission lines themselves, could surface in the appetite for risk by investor and financiers.

“Nobody wants to invest and banks don’t want to lend if your power plant is always the first to be curtailed. It changes curtailment risk enormously,” he said.

And one of the big questions is the impact on renewable energy projects built outside the REZs, both before and after the access rights were awarded.

Similar issues are likely to emerge in the south-west REZ, along the new transmission link to South Australia, with many in the industry regretting that a bigger transmission line was not built.

That is especially the case given the huge number of gigawatt scale projects that have emerged in the last two years in that region as developers discover a largely untapped wind resource and accommodating landowners.