New South Wales’ coal mining industry could disappear entirely as early as 2042 if global efforts to reduce emissions are successful, knocking 0.6 per cent off the state’s GDP and causing 22,000 job losses, according to a new state government report.

But the cost to GDP could be significantly mitigated through the rapid replacement of petrol cars with electric vehicles, boosting demand for locally generated electricity rather than imported petroleum. Under that scenario, the death of coal would cost NSW around 0.4 per cent of GDP by 2061.

The swift, early rise of EVs – hitting 5 million registered vehicles on the road in the 2050s – would help to ensure an orderly transition to a low-carbon grid and wider economy, protecting the state from the ravages of a messy, poorly managed transition, the report says.

Such a “disorderly” transition, it says, would be the most costly to GDP of all scenarios, even if it were accompanied by strong coal exports.

The rapid uptake of EVs envisaged in the “higher EVs scenario”, meanwhile, would likely require far more aggressive incentives at a federal level, something the Morrison government has shown a singular lack of interest in. Last month EVs made up less than 1 per cent of new car sales.

NSW is one of the world’s biggest coal exporters. Last year it produced 200 million tonnes of coal, 86 per cent of which was shipped overseas. Most of that was thermal coal used to generate electricity.

Thermal coal is generally first in the firing line in efforts to reduce emissions, because it is the most carbon intensive of all fossil fuels and, unlike metallurgical coal, it is easy to replace with lower carbon alternatives, from gas to renewables.

In the study accompanying its five-yearly Intergenerational Report, released on Monday, the NSW government said commitments by Australia’s three biggest export markets – Japan, China and South Korea – to reduce emissions to net zero by 2050 or 2060 could at best halve coal exports over the next 20 years, at worst destroy them completely.

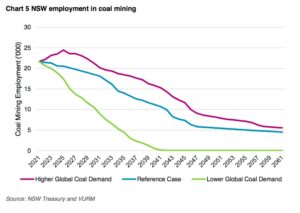

It said even if coal exports defied expectations and stayed relatively strong, 75 per cent of the state’s 22,000 coal mining jobs would be lost.

And it warned that if stronger-than-expected coal demand was combined with a “disorderly” transition to a low-carbon economy, that would be a net negative for the state, knocking almost 1 per cent off GDP by 2062.

And that’s before considering the complicated climate impacts of a scenario in which countries continue to burn coal without regard for the global carbon budget. At current emission rates the world has about 7 years before 1.5 degrees of warming is locked in.

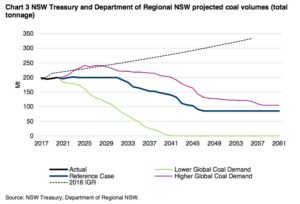

It’s a radical change of tune from the NSW government’s last Intergenerational Report in 2016, which predicted coal exports would rise steadily for the next 40 years.

As far as carbon budgets are concerned, we knew then pretty much what we know now, so the government’s bullish projection in 2016 was essentially a declaration of faith that climate change mitigation efforts would fail. But since then the global mood – and that within the NSW Liberals – has shifted markedly, forcing a rethink.

The NSW government modelled three potential scenarios for the state’s coal mining industry: high global demand, reference case, and low global demand.

In all three scenarios coal exports fall significantly, while coal mining jobs fall between 75 per cent and 100 per cent by the middle of the century.

Under the most optimistic case (optimistic for the coal industry, that is, not the climate), coal exports would rise until 2027, then fall to about half their current levels by 2061. In the low coal demand scenario, exports would end entirely by around 2042. In all scenarios, employment will plummet.

In the scenario of low global demand for coal, the report said higher uptake of electric vehicles “significantly moderates the negative economic impacts of lower global coal demand.

“This is because electric vehicles are powered by domestically produced and relatively inexpensive electricity, rather than imported petrol,” the report said.

“Under the slow and disorderly transition scenario, higher and more volatile electricity prices, combined with lower uptake of electric vehicles have a significant negative impact on economic growth, and result in growth being lower than under the reference case, despite higher global coal demand supporting higher coal production,” it said.