Carbon emissions have been rising since the start of the Industrial Revolution. But they’ll have to be curbed soon, and sharply, to keep the globe from warming above “safe” levels. A new report lays out avenues to get there and shows that while it’s possible, it’ll take a little human ingenuity and a lot of global cooperation.

A draft of the report, called the “Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project,” was delivered to the United Nations on Tuesday. It was developed by researchers working in the 15 countries that have the highest CO2 emissions and shows how each of those countries could rapidly reduce its emissions by 2050.

International negotiators looking to strike a climate deal have agreed to try to limit warming to 2°C. And scientists have outlined how much more carbon we can emit to likely keep warming below 2°C, calling it a carbon budget. It’s just like a household budget except going over it could increase the likelihood of major sea level rise, an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme heat events, and a rapid decline in Arctic sea ice.

“We’ve just about exhausted the carbon budget. The world is unfortunately engaged in a massive gamble,” said Jeff Sachs, director of Columbia University’s Earth Institute and one of the leaders of the new report.

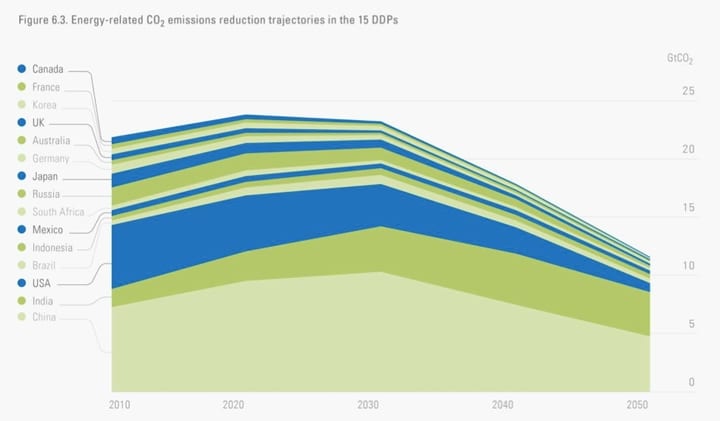

According to the new report, annual CO2 emissions would have to be slashed to 11 gigatons from our current level of about 36 gigatons by 2050. Put another way, each of the world’s 7 billion people is responsible for 5.2 tons of CO2 emissions each year (though much of that comes from developed countries). By 2050, there will be another 2.5 billion people, and annual per capita CO2 emissions will likely have to be reduced to 1.6 tons to keep warming within the 2°C range.

If that sounds daunting, it is. The world’s governments have failed to take meaningful action to get to those levels, in part because it means leaving a lot of fossil fuels, and the riches that go with them, in the ground. But it doesn’t mean it can’t be achieved.

“The basic conclusion of this report is the 2°C limit is achievable, but just barely. We’ve gone on so far with rising CO2 emissions, and greenhouse gas emissions more generally, that we’re just about out of time to meet this crucial limit,” Sachs said.

Rapidly cutting emissions will require efforts from individual countries and the global community and the use of both proven and emerging technologies. The report outlines rough pathways for 12 of the 15 countries to reduce their CO2 emissions based on their economic and population profile, with the other 3 coming in the next year. Generally, combined emissions from energy generation would have to peak around 2020 and decline thereafter.

While each plan is different, Sachs said energy systems across the globe do have some “shared DNA” and will therefore see some shared, and somewhat obvious, solutions.

Those shared solutions include improving energy efficiency and switching from carbon-intensive energy sources like coal to renewables by 2050. But for developing countries like China, coal use can continue to rise for the next few decades before declining and being replaced by renewables like wind and solar. But in countries like the U.S., coal use would have to rapidly decline starting this decade.

Current solar and wind technologies will play a role in meeting the low carbon pathways, but the report also assumes that more advanced versions of these will come online in the future. In particular, renewable energy systems that are able to efficiently store wind and solar power generated at off-peak hours and then feed it into the electric grid when it’s needed most will play an important role. These technologies exist but are currently costly and only available at select locations throughout the globe.

Similarly, the report proposes using carbon capture and sequestration technology at coal and natural gas plants to help reduce CO2 emissions by injecting carbon deep underground. There are currently only a handful of sites around the world that do this and questions remain about the best and safest way to sequester carbon.

Sachs said that to see if these and other technologies can be scaled to help meaningfully curb CO2 emissions, private and public investments are needed around the world. He cited the space race, the Manhattan project, and more recently, the human genome project as examples of projects where large investments produced relatively quick results. That’s something that’s been missing in the energy sector.

“The remarkable fact is we have not invested in an issue that is of existential importance for the planet,” he said.

There are still many unanswered questions about whether the world’s governments will be able to gather the political will to push these kinds of projects forward. Sachs said the goal of the current project was to show the feasibility of staying within a 2°C limit and that scientists working on the project specifically avoided discussing contentious issues of development, historical emissions and equality that have slowed international climate negotiations in recent years.

The report is timed to be available to world leaders who will attend a climate summit at the UN in September and a major round of climate negotiations in 2015. It could be guidance to show governments what a 2°C world would look like and why it matters, but not exactly how to get there.

“What would be an amazing breakthrough is to get governments to look at the carbon budget and to understand how tight it is,” Sachs said.

Source: Climate Central. Reproduced with permission.